ARCHIVE

PRISONER OF FLESH

words by Michele D’Aurizio

Courtesy of the Artist

Case had become a prisoner of his own flesh. The thief he was, he had stolen from his employers, who instead of killing him had chosen to cripple his nervous system, depriving him of the capacity to access cyberspace. For Case, this was an expulsion from the Garden of Eden.

The scenario by which it is possible to transcend the human body by means of technological innovations remains the subject of science fiction, and thus Case’s misfortune is the starting point of the novel that, more than any other work of Western literature, serves as the bedrock blend of cybernetics and underground culture realized in cyberpunk imagery: William Gibson’s Neuromancer. Set in a hyper-anthropized world, a hypertrophied suburbia peopled by androids and cyborgs and ruled by nameless economic and technocratic powers—an environment of which cyberspace constitutes not so much a replica as a simulacrum—Neuromancer celebrates a planet on which nature is no longer a part of everyday life. Likewise, human beings have entered into an alliance with technology (and, in some cases, physically incorporated its fruits), becoming pioneers of a new intelligent species fated to intermingle with the human race and eventually supplant it completely.

The stories that have helped to construct cyberpunk imagery, pop versions of the more daring post and trans-human theories, see the human body as the terrain on which the future will be played out: a modifiable technology, ready to accept grafts of software and hardware that boost its physical and mental capacities, to outlive itself, to become more human than the human. “Man remaining man, but transcending himself, by realizing new possibilities of and for his human nature,” as Julian Huxley wrote in 1957. According to transhumanists, so long as the desire to outdo what has been given by nature is part of what it means to be human, the desire of the human being to improve through technology is the most intimate and sincere manifestation of the self.

Courtesy of the Artist and Real Fine Arts, New York

Yet transhumanism has always had more detractors than adherents. The assumption that the human race ought to encourage the progress of nanotechnology, biotechnology, information technology and cognitive science (NBIC), as well as such hypothetical future technologies as artificial intelligence, mind uploading, cryogenics, etc., in order to expand the individual’s intellectual and physical abilities, sounds to many people like anything but a good idea. Too fraught are the paths leading to the Fountain of Eternal Youth, too “barbarous” the many Frankenstein’s monsters who might populate the future. Without abandoning faith in the progress of science and technology, the difference of opinion arises from misgivings over whether humanity will really be able to master the technologies that the transhumanists yearn for.

Such nightmare visions are fomented by the sociopolitical dystopias lurking behind transhumanist theories, the fears that the widening of the gap between wealth and poverty would necessarily lead to the emergence of a divide separating those who are able to benefit from the technologies for the improvement of their bodies and those who are limited to what has been provided them by nature. These fears, of course, are rooted in the memory of the aftermath of the old eugenic ideologies, the banners of supposed superior races: separation and discrimination between the “boosted,” the “improved” and the “natural” are repercussions that are only too likely to come true.

Ethical concerns expressed over the no longer clear-cut division between technology and biology are often academic and long-winded; perhaps in an attempt to countervail the laconic fear that characterizes the present, the insistent white noise, the tormenting paranoia that the technophilia that is growing among the human race might lead to the ineluctable eclipse of the natural, the organic, and the experience of the world “through the flesh.” To be “synthetic,” “inorganic,” is also to be “desensitized,” “non-emotional,” or even “anti-emotional.” The products of technology do not have feelings.

Photography by Joerg Lohse

Courtesy of the Artist and 47 Canal, New York

On the occasion of his first solo exhibition at the New York gallery Foxy Production, Andrei Koschmieder showed a series of twoand threedimensional works, made from a combination of epoxy resin, painter’s inks and digitally processed images, which evoke the experience of touchpad technology. Koschmieder focused on the hand, the part of the human body responsible for the act of making, and the supreme “sensitive” device: the hand was caught in the attempt to turn pages, click on a button, zoom in or out on a screen. When the interaction with reality takes place through the go-between of a screen, the senses take on an abstract quality and sensations are treated like entries in a drop-down menu; the body is dematerialized into the codes of an avatar, its limbs become gangrenous. An anatomical representation remains to echo the vitalism that was once there. In Koschmieder’s works the figure of the hand is always grotesque: positive because it brings knowledge, negative because it is atrophic, and forgetful of the emotions that stem from the act of touching. Those works, fusions of organic and synthetic, as transparent as computer data, are hybrids in which the device—the touchpad—directly incorporates (at last) the most human of interfaces, the hand.

Koschmieder’s works, however, do not represent the apogee of a posthumanist art—at least in the sense in which art understands posthumanism, (i.e according to the assumptions laid down in the travelling exhibition “Post Human,” curated by Jeffrey Deitch at the beginning of the 1990s). For, while it is possible to trace aesthetic parallels with the scenarios evoked by postand transhumanist theories and conveyed through the symbolic and mythological repertoire of cyberpunk, the dispersion, through systems of consumption, of the imagery of many of the subcultures that have emerged in recent decades has contributed to the creation of a mass language that finds an effective means of communication in that repertoire. Thus transhumanism has become an immanent phenomenon, to the point that the disintegration of the process of mechanization, desexualization and reification of the human body can take place only through a short-circuiting of that language— a perverse, literally anti-humanistic, over-identification with the “dark will” of technology is the only road to be taken for a reassertion of humanity over the machine.

Photography by Mark Woods

Courtesy of the Artist and Foxy Production, New York

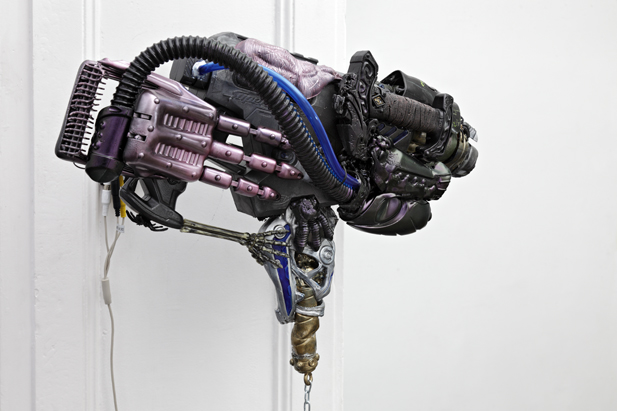

From this perspective, the cyborgs/androids that Stewart Uoo presented in his first solo exhibition at 47 Canal, in New York, and the telecameras of Nicolas Ceccaldi, presented recently in the artist’s solo exhibition at the Neue Alte Brücke, in Frankfurt, are paradigmatic. See the former’s three female mannequins cast in polyurethane resin and woven through with barbed wire and electric cable, eroded by the weather and “cooked” under the sun, worn-out and dressed up in trashy street styles and finally put on display mounted on vertical posts in the manner of classical statuary, and the latter’s science-fiction reinterpretations of the CCTV, which are more like otaku gadgets than surveillance devices, in some cases associated with monitors to obtain phenomena of video feedback. The two artists’ works suggest two hypotheses of the degeneration of humanity, familiar from the dystopian visions commonly found in cyberpunk fiction: on the one hand, the maximum degradation of civilization, a post-apocalypse dominated by post-human beings; on the other, the advent of panoptic powers, forms of totalitarianism able to control every aspect of life. In both hypotheses, the natural is not contemplated, and where it does emerge, it is as an instinct to be suppressed, a fanaticism to be quashed.

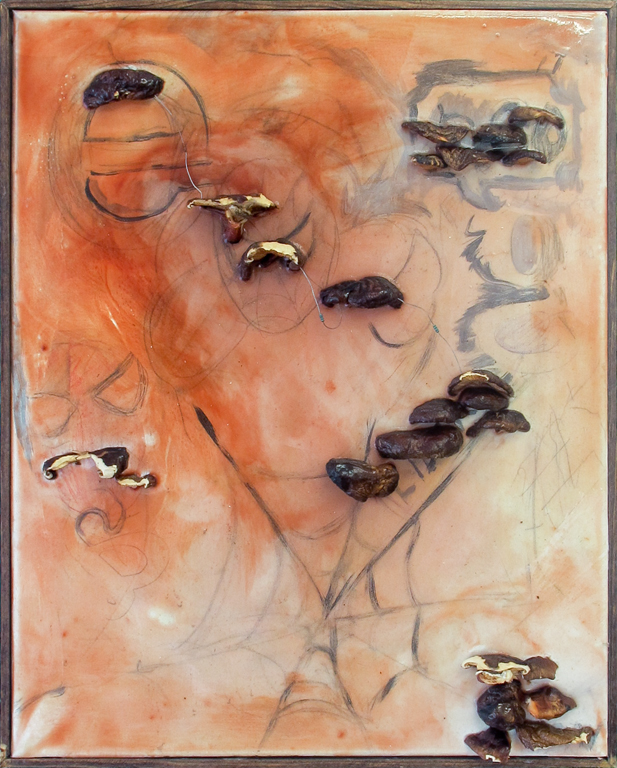

Accordingly, a regressive attitude, not wholly devoid of black humor, a sort of Gothic materialism, pervades these lines of artistic research. Not without smugness, an ironically homeostatic state of crisis is observed, as if the tendency to degeneration, to disorder, were the latest reincarnation of entropy. Here the human being is lesh, matter and nothing else. Mathieu Malouf, meanwhile, creates works on canvas with oil paint, epoxy resin and parasitic fungi, often connected together with electrical resistors. In these works, to quote from the press release of the artist’s last solo exhibition at Lars Friedrich, in Berlin, “trace amounts of electrical current generated by the bacterial culture transplanted from Malouf’s humid basement to the linen’s weave circulate along the matrix of interconnected lumps, simulating a level of neural activity comparable to that of a human brain’s during a prolonged period of cryogenic sleep. Fossilized in a coat of medical-grade silicone or hypoallergenic moulding latex, these neural configurations remain active: they think.” Malouf’s works are also fusions of the organic and synthetic, and like true cyborgs, are alive.

Thus the human being is evoked; organ by organ, his or her body is reconstructed, not necessarily in a manner faithful to anatomy, not necessarily so that it will function fully. Yet rejection of the anthropocentric vision, that strategic anti-humanism, leads to neglect of the self, of being as an emotional state. As a result, the perversions of the humanist ideal of a rational, autonomous human being endowed with free will are examined: colonialism, totalitarianism, laissez-faire economics. In fact, it is through a retroactive criticism that the transhumanist theories can be updated, purified of their evolutionistic aspirations and dystopian prophecies; a criticism that, even if only momentarily, puts aside the question of identity.

Photography by Nick Ash

Courtesy of the Artist and Johan Berggren Gallery, Malmö

Still along the lines of a materialistic interpretation of the human body, Timur Si-Qin, in his solo exhibition at Mark & Kyoto in Berlin, brought into question the relationship between the body and the consumer product. In the pamphlet that accompanied the exhibition, the artist wrote: “The body, when combined with the manufactured good, designed to fit in the hand and mould to the skin, can be seen to form a sort of synapse over which the information of our evolutionary history is propagated into structures of manufacturing and industry; driven in part by mechanisms of selection like consumer choice and commercial competition.” So Si-Qin has shifted his attention to the role of ergonomics, as a scientific discipline capable of fusing the natural with the technological object and its role in the economic system: “The ergonomically designed product therefore becomes the reflection of the body: a symmetry expressed through tools and systems, paddings and curves. The imprint of humanity, as carried by metals and rubbers, is therefore like the symbolic figure represented by the image of the hand in prehistoric cave markings.”

But what is the limit beyond which materialism obstructs the spontaneous process of affirmation and definition of the self? Works like Yngve Holen’s household appliances that have been cut in two with a jet of water show the technological object stripped of its functionality, helpless, like a brain in which the right side has been split from the left one and both sides are presented to the viewer in all their gruesome anatomical accuracy. The act is so analytical, surgical, that even the most remote iconoclastic intention does not stir the slightest compassion.

The artistic practice of Jana Euler, on the other hand, analyzes the human body in its capacity to evolve, reflecting the gradual, complex development of the self. In her solo exhibition at Real Fine Arts, in New York, three paintings were arranged in such a way that their perception by the viewer could replicate a multistage journey, symbolic of transformations in the body of a woman and of the countervailing forces that foster her identity. In Euler’s works the human being is defined by context rather than by universalizing power; by the friction between the image-form of what is and that of what is wished to be; by the ability to express oneself through multiple identities, instead of being steamrolled by a presumed relativism. Here the anti-humanist position is transcended in the delicate union of nature and culture, art and reality; in the desire (perhaps actually posthumanist) to recognize human beings as imperfectable and not homogeneous—or complex, so as to reflect the heterogeneity of the world that surrounds them.