ARCHIVE

LYNETTE YIADOM–BOAKYE

interview by Hans Ulrich Obrist

Courtesy of Corvi-Mora, London

HANS ULRICH OBRIST In your paintings you have a very clear methodology, which is actually quite conceptual. It sounds like, in a sort of On Kawara way, a painting a day. Can you talk about this? It seems that with a painting, no matter what, you finish it.

LYNETTE YIADOM-BOAKYE Yes, exactly. That started off as being a practical consideration: the way I was initially painting, if I didn’t finish in a day the surface wouldn’t work, it would dry at different times, so it was completely a structural thing. Then I started to realize that the way I was working was as important to the work itself as the finished product, it was about reading between works rather than becoming very precious about one. It’s to do with the way I think: I say it’s a short attention span, but what I mean by that is that it’s one thought and it’s fresh in my mind. It’s about a certain kind of urgency and capturing that time frame. Because if it were dragged out over days I feel like the whole resonance of it would go, it would become a much more labored process and I would personally become too precious. If I get to the end of the day and something hasn’t worked I don’t sleep well. I’d rather destroy it than think about it over night just to come back and try and force myself to like it.

Courtesy of Corvi-Mora, London

HUO It’s interesting also because you say that you don’t fix the particular narrative behind it. The paintings are like snippets or part of something, it’s almost like the viewer writes the stories. Duchamp said the viewer is half of the work, Dominique Gonzales Foerster says the viewer does at least half of the work. It seems to be the case with you as well.

LYB I give all I can, as I think seduction is very important. I love painting. I love the surface of it. I know how it makes me feel when I see certain works or when I’m in the presence of works that I really admire, and I think the pleasure for the viewer comes out of that kind of feeling, rather than me trying to tell a story. It’s a sensual thing—it’s about a sense of touch and a sensibility. I want it to be that kind of experience as well, which is why I don’t like the idea of giving too much of a story and trying to control that response too much.

HUO You say in all your texts and interviews that you conceive the paintings as groups, and think of how they could work together. Can you tell me a little bit about the main groups in your work?

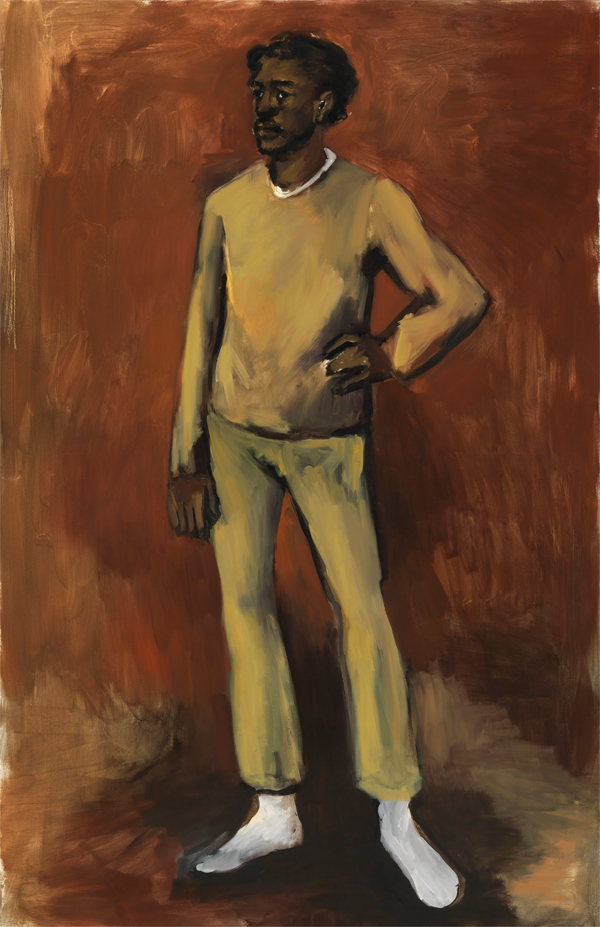

LYB They develop over a period of time, and relate more or less directly to what I’m thinking about at the time. I try to put as many different things into a group as possible and often things that relate to each other. There are paintings that come in pairs. But I don’t necessarily show them together. There’s a recurring pair that goes into every body of work. When I start a body of work I will do these two paintings and each time there will be a slight variation but essentially it’s the same man. He’s always wearing basically the same thing, always facing in opposite directions, the pose changes and the facial expression changes slightly, so he’ll always come into that group and there’s always a man in a stripy top. In a way they are like an anchorage. Somehow they start the body of work and then from there everything kind of builds around them. It changes each time. More recently I’ve been trying to paint a lot of landscape, and I’m not very good at it. (Laughs.)

Courtesy of Corvi-Mora, London

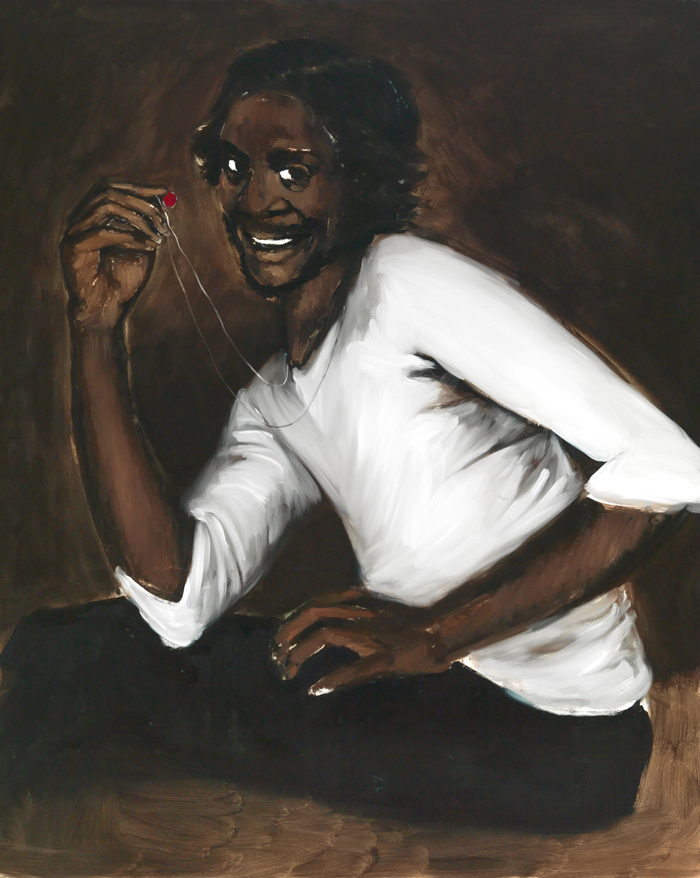

HUO I wanted to ask you about these two characters. They are larger portraits filling the canvas completely and almost coming out of the wall. You say that they are always there, these figures, one has a stripy top and the other one not. So how did they enter? You have often mentioned that this is a recurring element but I didn’t find any literature on how they entered into your work. How did you have the epiphany? How did these two guys pop up?

LYB They happened quite separately. The really big ones of the man with the white top, the massive ones that always come as a pair, they started of as a very small work. It was a triptych of three of that man and there was something in the facial expression that really captured everything for me, everything that I was trying to do somehow. Really, if I had to choose two pieces that encapsulate the spirit of what I’m trying to do, it’d be him and the stripy man. When I say capture everything I’m trying to do, or the spirit of what I do, I mean the way that I think, the way my sense of humor works. When I start a body of work they are a good reminder, if you like, an anchoring of how I think generally and the reminder of where I am. It is also the sense of getting to know someone better. They have changed a lot since their first incarnations.

HUO And what about the stripy one?

LYB Again it’s like they are opposite poles of the same thing. So there are two emotions there. There’s this calm, sense of something level and almost elegant in the stripy man, and then the white shirt is far more like a sphinx I suppose.

Photography by Marcus Leith

Courtesy of Chisenhale Gallery, London

HUO I’d like to talk about the characters that you invent for each of your portraits. Your fictitious characters are all black people, and you have said that that it produces a kind of normality. I wanted to ask you about this, and to what extent you view this as a political gesture.

LYB I think it’s always in some way going to be political. But for me the political is as much in the making of it, in the painting of it, in the fact of doing it, rather than anything very specific about race or even about celebration. I don’t see what I do as at all celebratory, because to me it just is. The fact that they are all black is double edged as well. They’re all black, or what I should say is they are all tinted black or brown—some of them actually have black features, others have completely Caucasian features—but they are still sort of black. For me, that is the normalizing aspect. It’s not normal, because they’re not real people, but at the same time that means also that race is something that I can completely manipulate, or reinvent, or use as I want to. Also, they’re all black because, in my view, if I was painting white people that would be very strange, because I’m not white. This seems to make more sense in terms of a sense of normality. I suppose with anyone doing anything you set yourself certain parameters, it’s not about making a rainbow celebration of all of us being different. It’s never seemed necessary to alter the color of people just for the sake of making that point.

HUO You also say in a statement that you don’t like to paint victims. Jennifer Higgie says it’s a kind of empowerment, kind of power to the people.

LYB Absolutely. I said that many years ago in relation to how I like to think about how I finish a person, how a person should look in a painting, and what I want their expressions to be. One of the things I always destroy in the work is anyone that I think looks passive. In part, this is because they’re black, and in part because I don’t want them to like anyone has taken anything from them. I don’t want them to be victimized basically, or to look that way. It’s as much about avoiding certain tropes in the work as anything else.

Photography by Marcus Leith

Courtesy of Chisenhale Gallery, London

HUO I would like to ask you about Ghana, as your family comes from there. I was wondering if you have any connections to Ghana or to Africa?

LYB Not very strong ones. I mean, my strongest connection is my parents.

HUO Who live there?

LYB No, they live here in London, and they have for forty years. But just the fact of them having raised me the way that they did, they are my connection. I kind of have an idea of Ghana from them, but I wouldn’t say I have a strong personal connection with it, in that I haven’t been there that much and I certainly never lived there. I wasn’t born there—I was born here, and I was raised here. Really my connection is through my relatives, the people who raised me, and their way of thinking, which to me is very much Ghanaian, and that has obviously effected how I think and what I think about. But it would be disingenuous of me to claim some strong connection with Ghana as a place because I don’t really know it and I wasn’t raised there.

HUO But it’s there through the transmissions of your parents.

LYB Definitely. The way I always put it was that Ghana is present as a way of thinking and a way of seeing, which has influenced me.