WEB SPECIALS

THE ASIA CONVERSATIONS:

Pratchaya Phinthong with Nick Warner

Photo by Mark Blower

Nick Warner: How did you go about producing your recent exhibition at Chisenhale? I’ve been looking forward to getting a first hand account of this enigmatic show.

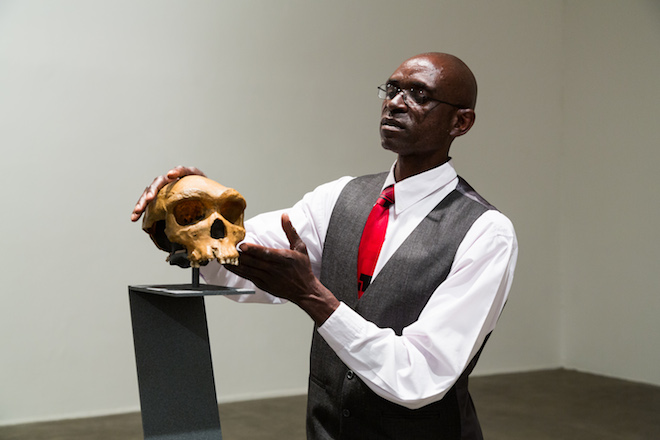

Pratchaya Phinthong: My friend Jakrawal Nilthamrong, a Thai filmmaker, had been in Zambia shooting his film Unreal Forest (2010), which is a mixture between documentary and fiction. Jakrawal told me a story about an “antique object” on display at the Lusaka Museum, which was a copy of a display in a London museum from a long time ago. A year after I met Jakrawal in Bangkok, I asked his friend, a local Zambian filmmaker who had worked on his film, to produce a film about this unknown object. I’m interested in making work from scraps of memories and reconstructing it with help from others. My Thai friend Pattara Chanruechachai accompanied me and I paid the local filmmaker Musola Catherine Kaseketi and a taxi driver $2,500 for two days to make this film about the mystery object. Musola was free to determine her own script and framework. The first day Musola decided to shoot Pattara and I approaching the museum and greeting the guide who explained the history of the museum to us, specifically the Kabwe Skull or “Broken Hill Man Skull.” We learned from the guide that this ancient skull was excavated in Kabwe town where an Australian mining engineer, Tom Davey, had discovered a rich and complex mixture of minerals in the ground. He named the new mine “The Rhodesia Broken Hill” after a comparable mine in his native Australia. In June 1921, about 30m below the surface, miners found a cave with a human skull on a ledge. The skull was miraculously untouched by the explosions used to excavate the mine. The miners displayed the skull for a few days on top of a flag pole, yet the potential value of the skull was soon recognized by the mine doctor and the mine manager, R.K. McCartney, who personally took it to the British Museum in September 1921. Sir Arthur Smith Woodward, the keeper of Geology there, gave it the name Homo Rhodesiensis: Rhodesian man. Musola immersed herself in the story and made appointments with people who had been involved with the skull. She interviewed a playwright in Kabwe town who did a play in Lusaka Theater about the skull in 2005 and an artist took her to the dig site where the skull is believed to have been excavated. We went back to Lusaka Museum and met the museum director, who later allowed us to handle the skull personally.

Photo by Mark Blower

The skull is made of resin, and “British Natural History Museum” is inscribed on the back side of the jaw. I asked the director what would be required to borrow the skull for an exhibition in another country. He said that the museum would need an official loan form and that the museum guide would have to travel with it. As such, the materials for the exhibition at Chisenhale were decided by the Zambian director for me.

NW: Story telling and anecdotes seem important to you in this project. The reason you started the project was because a friend told you about this object. Further research about the skull revealed more stories about its discovery, its transposition to the museum, and then the classic narrative twist of it transpiring to be a replica. Is this sort of extended narrative trajectory important to you? The narrative arc of the museum guide seems like a central concern of yours.

PP: Mr. Kamfwa in London is somehow the inverse of my role in Zambia. He was invited to have conversations and meetings with diverse people, people who think differently than those who he sees everyday. These experiences will be told to his fellow citizens when he returns, which might be called the “extended narrative.” The story of the skull is now changed from what I first heard about it. For me, the past is unique[...]. I asked Mr.Kamfwa to use the 701 pictures that he took on the trip to make two identical albums, one for him and another to travel as a part of the piece.

NW: There also seems to be some significance in bringing this object to London, along with the Zambian museum guide. The skull was something that was excavated in Zambia and then transported to a collection in London, and now you have transported the replica made to fill its place. Is there an intended critique of the colonial/post-colonial dialogue at play in this piece?

PP: I’d rather allow the audience to answer this question.

Coproduction CAC Brétigny / GAMeC Bergamo, 2010

Courtesy of the artist; and gb agency, Paris. Photo by Jacopo Menzani

Installation view of "Give More Than You Take," 2011 at GAMeC- Galleria d'Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Bergamo

NW: It seems important in your work to give the responsibility to other people. You gave Musola a budget and told her to make the film however she saw fit. Then the museum’s loaning policy determined the content of the Chisenhale exhibition. For the show itself, Mr Kamfwa performed/discussed the skull every day. In your project Give More Than You Take (2011) you had the curator’s of the respective institutions conceive of much of the display in your absence. Why do you think this is important or interesting? Is it about translation? Do you feel empowered making work this way?

PP: Giving responsibilities away is a platform to share “possibilities.” I compose these possibilities and apply them to contemporary art spaces. I’m interested in what lies between them. Whether post-colonial critique emerges from the exhibition or not, we’re still left with the reality that someone has delegated responsibility to someone else, which is like the empowerment game that society plays. The project Give More Than You Take explains this scenario, where the translation and contribution are visibly a part of the work, and create a platform for discussion.

NW: A Piece That Nobody Needs (2012) is a commission with global concerns at its core, perhaps even more explicit than the Chisenhale show. Do you intend to address the discourse on climate change, or is this, again, something you claim is there for your audience, but not prescribed?

PP: A number of my works have global concerns, but this specific selection of works invites you to consider the invisible relationship between the concrete building and the melting glacie.