WEB SPECIALS

REVIEW:

7TH BERLIN BIENNALE

words by Anca Rujoiu

Courtesy of Berlin Biennale

Photography by Marta Gornicka

The 7th Berlin Biennale sets up clear expectations through a straightforward curatorial statement about what it embraces, excludes and loathes. When one’s expectations are clearly defined, the risk of disappointment is greater; once one knows exactly what to look for in the Biennale, it is easier to grasp what it fails to achieve. The curatorial statement—a mixture of an organizational plan with tangible outcomes (finding answers, implementing solutions, bringing change) and a complaint letter (against curatorial practices, art autonomy, intellectual discourse)—outlined the criteria by which the visitor judges the Biennale. Leaving no room for interpretation and eschewing the open-end discourse, Zmijeveski and his team (associate curators Joanna Warsza and the art collective Voina) set themselves up for critique. Alongside negative reviews, the Biennale produced platforms for debate and critique which highlighted its inherent contradictions.

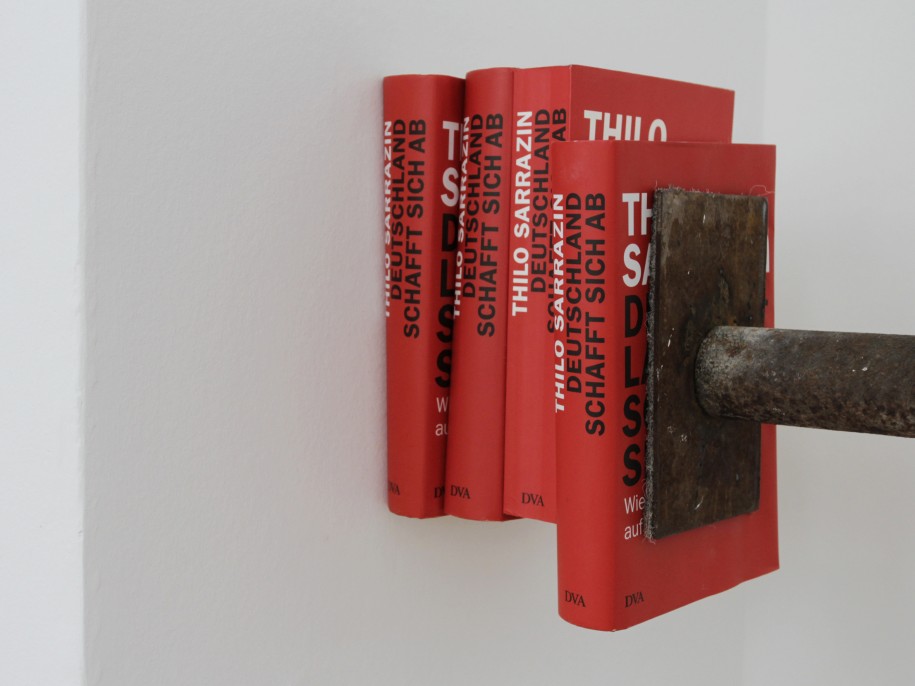

Driven by an ambition for visible social impact, the 2012 Berlin Biennale’s mission is to make art work and put ideas into practice. To achieve this concrete objective, the curators followed a specific methodology that provided a certain coherence to the Biennale in terms of embodying a set of distinct, visible characteristics. The attempted shift from artworks as objects to artworks as projects (discursive practices) shaped the durational nature of this Biennial and its fluid temporality. The curators decided to focus on a set of ongoing activities rather than a selection of works “hung on the walls.” One of the Biennale’s most debated project, Deutschland schafft es ab (Germany gets rid of it) by Czech artist Martin Zet was launched a few months before the Biennial’s official start in a campaign in which the artist made a call for donations of copies of Thilo Sarrazin’s Deutschland schafft sich ab (Germany does away with itself), a book widely criticized for its racist content.

Courtesy of Berlin Biennale

Photography by Mirosław Patecki

Pawel Althamer’s Draftsmen’s Congress is a continuous drawing session in the St. Elisabeth Church; members of the Occupy movement are running their daily activities throughout the duration of Biennale; whereas the sculptor Mirosław Patecki turned the first floor of KunstWerke into his studio to create a replica of Christ’s head during the exhibition. In some of the reviews, the Biennale is often perceived as one single project, more specifically as Zmijeveski’s artwork, which wouldn’t be problematic if it didn’t clash with the Biennale’s expressed turn towards a performative democracy, active participation and an inclusive system of values.

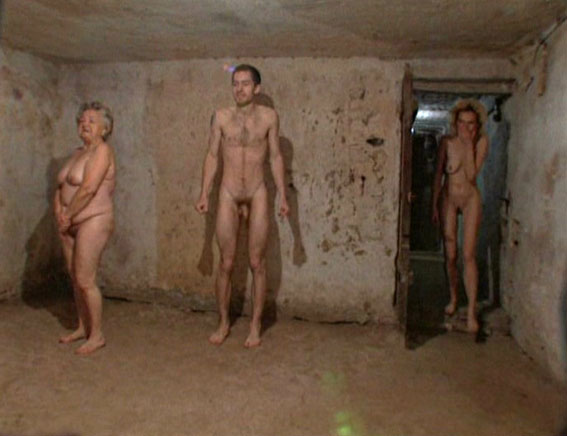

The dichotomous rhetoric of the curatorial statement (us versus them; autonomous art versus political art) extends to the Biennale itself, which instead of blurring distinctions makes them even stronger. At KunstWerke, the Biennial’s main venue, the physical display of the projects engenders hierarchies and inevitable distinctions between artists and non-artists to the point that the debate over good/bad art gets stuck in your mind and follows you obstinately through the venue. The journey starts from the ground-floor of KW, where the Occupy movement has been invited to “occupy the Bienniale” and run their activities. On the last floor, the projects gradually turn into individualized and artistic entities culminating with Zmijeveski’s Berek (1999), a strong work, more impactful and present than the presence of Occupy movement.

Courtesy of the artist and Berlin Biennale

As political as poetic, Joanna Rajkowska’s work - Born in Berlin shown at Akademie der Kunste stands out. Based on artist’s decision to give birth to her daughter Rosa in Berlin, the film work documents various moments of the artist’s pregnancy process, capturing the artist exploring the city with her body, introducing Berlin to her unborn daugther: its places of trauma and wound, illustrating the strong relationship between us and our place of birth and the possibilities to shape and define each other. Rajkowska explained her decision to give birth there in terms of making a gift to Berlin, which suggests not only a new life in the city, but also the hope for a new life for the city.

As a method of research, the curators proudly state that they have not embarked on studio visits, but preferred to follow the news and turn the Biennale into an arena of current political events and manifestations tuned to reality. In one of videos posted on the Biennale’s website, Pawel Althamer expands on his project. Walking around Berlin, surrounded by buildings with tags and graffiti asserts that Draftsmen’s Congress attempts “to give all activity that surrounds us a slightly more enlightened and civilized form.”

Not only does the Biennale look at the idea of political from one single perspective, it approaches political gestures and manifestations in such a serious and civilized manner that the projects look completely uninteresting, easily to ignore or hard to take seriously.