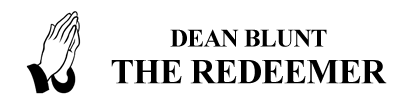

ARCHIVE

TALA MADANI

words by Chris Wiley

Courtesy of the artist and Pilar Corrias, London.

Photography by Joshua White

On a recent visit to Tala Madani’s spacious studio in Los Angeles, a small, unfinished painting caught my eye. In it, a child totters sweetly in its crib, proffering an object that looks like an abnormally large bird skull to a fat, Middle-Eastern-looking man. The man, naked save for the pair of tiny black briefs out of which his cock hangs lazily, seems to acknowledge the child’s gift with an air of patrician indifference as he goes about his main task: pissing into the child’s crib. Seeing this, I laughed out loud. “Take that, kiddo,” I thought, “there will be more where that came from.”

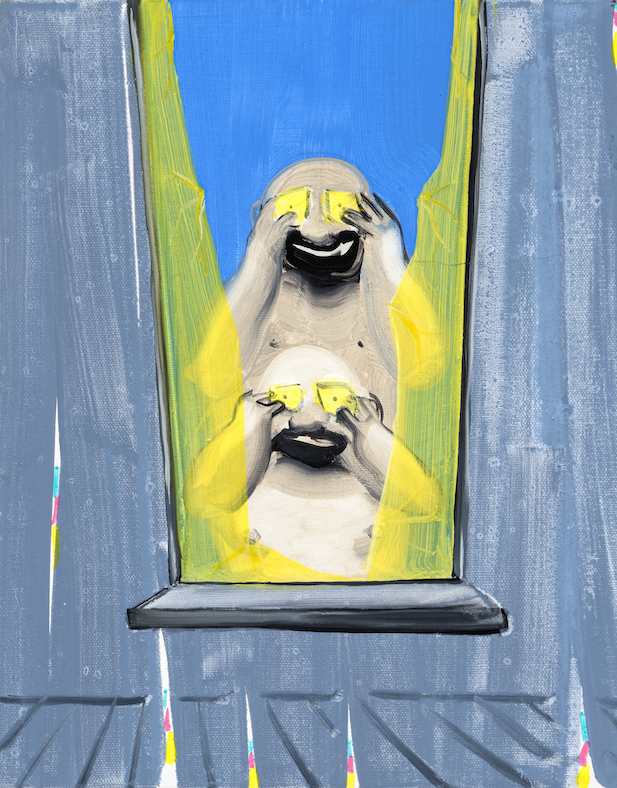

This kind of grimly gleeful and casual cruelty, rendered in an impish, cartoony style, is a hallmark of Madani’s paintings and stop-motion animations, whose subjects are unfailingly men, who almost exclusively appear to be of Middle-Eastern extraction. Much has been made of this latter fact, especially since Madani is a woman who spent her childhood in Tehran, Iran, before moving with her family to the United States when she was thirteen. Indeed, it seems that the gender and racial make-up of her subjects is one of the only aspects of her paintings that is commonly spoken about, and often in a fairly typical way. Consider, for example, paintings like Pink Connection (2008), in which a man stands with an erection that strains his briefs as he proudly holds aloft a bright-pink enema bag, its tube snaking out of his ass like a vestigial tail. Or see the more recent Chinballs with Flag (2011), in which the subject, whose pendulous, stubbly jowls recall giant testicles, hangs a flag that sports a facesized hole cut above a cartoonish ball sack in front of his male companion, giving this latter man the appearance of having a similar facial mutation. The customary read of these works (by critics, anyway) takes these bizarre psychosexual vignettes and hangs them on an easy metaphoric deployment of abjection that amounts to mere Western finger wagging.

Courtesy of the artist and Pilar Corrias, London.

Photography by Joshua White

These male subjects and their shenanigans, in such a view, are painted ciphers for the raging male id behind the theocracy-ordained misogyny of Madani’s home region, whose extremity is but a desublimated version of our North American variety, where outright authoritarianism has been veiled behind a scrim of hand-wringing piety. Depending on your dispensation, this reading may be true — Madani is insistent in her assertions that the meaning of her works remain open — but it is certainly not that interesting, or subtle.

That being said, Madani’s choice to cede the imaginative territory of her paintings to a demographic that is the closest equivalent that the Western world has to a boogieman is certainly not something to be quickly dismissed. But rather than turning this presumed critique directly around on Madani, and assuming that she is attempting to make a point about her embattled status as a Persian woman, it is perhaps more germane to speak of the way the men in her paintings behave, and how that might reflect on our collective ideations surrounding the figure of the ever-abstracted and displaced Middle-Eastern male. A good place to start, in this regard, is with one of Madani’s earliest body of paintings, from 2006, that she refers to as her “Cake Series.” In it, Madani’s men enact strange rituals of sex, sadism and humiliation, centered rather incongruously on tiered, pink birthday cakes, whose icing is slathered on bodies, spongy innards are poked and penetrated, and candles are used to burn and brand. It is a Sadean carnival of epic propotions, made more menacing by the benign nature of its primary totem. Here, one of the most universal of celebrations — the celebration of birth, and by extension, of life — has been transformed into its dark other, in which depravity is the order of the day.

This type of inversion, in which activities that have the flavor of boyhood games go awry when played by adult men who should have left them behind, allowing repressed psychic violence and physical aggression to come bubbling to the surface, has remained a vital vein in Madani’s paintings ever since. These paintings are often funny, but whether consciously on the artist’s part or not, it is nevertheless impossible to look at them and not think of the most iconic images of violence visited on Middle-Eastern men in the past decade of war: the photographs of the American-run prison Abu Ghraib in Iraq. Of course, the horrific violence — often masked as a kind of diabolical play, exemplified most succinctly by US Army Reserve prison guard Lynndie England’s callous thumbs-up, printed in newspapers around the world—perpetrated against the inmates of that dusty, hellish prison was not enacted by Arab men on one another, as it is Madani’s paintings. However, it is the Western perception of Middle-Eastern male sexuality that her paintings play with, and force us to examine.

Courtesy of the artist and Pilar Corrias, London.

Photography by Joshua White

Classically, the way in which the West has sexualized its male others in the process of building architectures of oppression has been to see them through the lens of hypersexuality. Thus, we have the image of the savage “African,” hell-bent on raping innocent white women, just as, historically, we have the image of the sensuous, mysterious “Arab,” with his harems of belly-dancing women and his knack for seduction. But, almost as soon as the dust settled after the Twin Towers were impaled and fell, this latter image underwent a radical shift. Popular justifications for the attacks began to include the salacious, much-contested detail of the seventytwo virgins that supposedly await Islamic martyrs in paradise, with the implication being that this new terrorist threat was, in part, a form of violent sexual release, manufactured by the repressive nature of fundamentalist Islamic society. A new type of sexual other was born: a thoroughly repressed one, whose thwarted animal urges were routed into aggression.

This, of course, is the variety of sexual otherness that crops up frequently in Madani’s paintings, but their weight does not spring from mere representation. At Abu Ghraib, this revised perception of Arab male sexuality was effectively weaponized, and sexual humiliation became most prized American torture tactic. This created a terrible irony: in light of the concurrent rising tide of conservative shamemongering and fundamentalist Bible thumping on the home front, it appeared that our perceptions of our enemies were, in fact, also reflections of ourselves. So too do Madani’s men become everymen, who hold up “dark” mirrors that reflect our desires and drives in all their unflattering complexity.

Ultimately, once these essential political conundrums have been picked apart and put temporarily to the side, it is this scrutiny of the warp and weft of desire that is at the heart of Madani’s oeuvre — its tragicomedy, abjection and fathomless, murky depths. Her paintings brim with desire’s grit, not just by way of the nature of the situations that she depicts, but equally through her loose, sensuous facture, which has the virtue of seeming ebullient but never rushed. Though her subject matter is mined and her themes weighty, Madani nevertheless manages to avoid the entropic pull of dour self-seriousness with a charming insouciance and wicked sense of humor that roots her work in one of desire’s most redeeming facets: joy. Not a joy that is unmitigated, unfettered or naïve, but a provisional joy, a kind of gallows exuberance. We are inextricably mired in our own shit, Madani seems to say, but if we can’t find a way to laugh about it, then we are doubly doomed.