ARCHIVE

PIERRE HUYGHE

interview by Barbara Casavecchia

BARBARA CASAVECCHIA This summer, I read Douglas Coupland’s book on Marshall Mcluhan, You Know Nothing of My Work! and found something I thought you might like: Mcluhan says that the work of the artist is to find patterns.

PIERRE HUYGHE Douglas and I collaborated years ago on a book based on a collection of high school yearbooks (School Spirit, Dis voir, 2002) that chronicle the students’ lives in the institution. It was an attempt to construct a character that would narrate what was there in the existing material but had not directly appeared. Flipping through the pages, you started to see fear, jealousy, sexuality, violence expressed unconsciously and indirectly through fragments of sentences and images, and the development of a person under these conditions. We developed a process of editing that focused on recurring behaviors, and patterns appeared.

BC There is also another side of that biography which I have associated with some of your works. Everybody knows Mcluhan’s meme, “the global village.” In the book, the notion of retribalization, as a psychological response to the expansion of electronic media, keeps resurfacing, together with Mcluhan’s interest in rituals and celebrations, subjects you have been working on extensively.

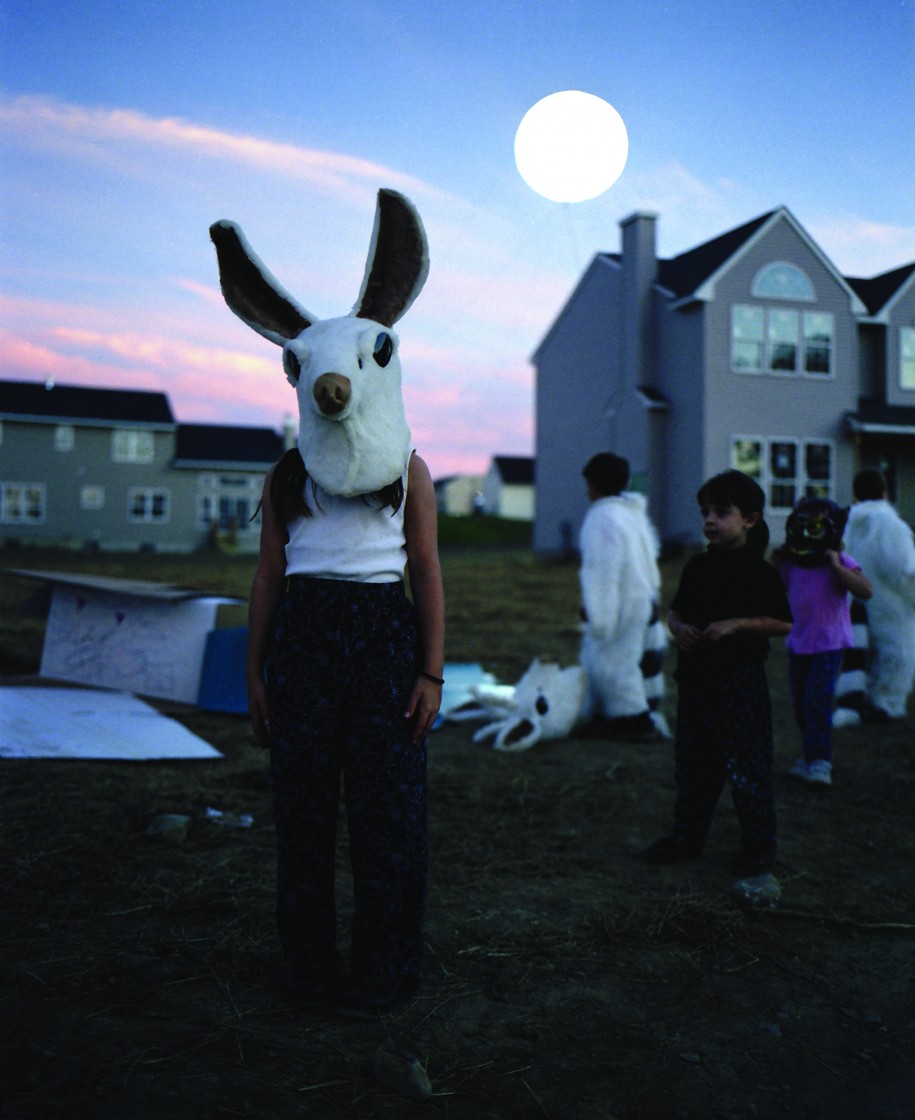

For Streamside Day Follies (2003), you orchestrated the founders’ parade in Fishkill, a new suburban community on the Hudson River, in upstate New York. For the project One Year Celebration (2003–06) you invited 48 artists, friends, architects, musicians and writers to propose dates for new celebrations that could be added to the calendar. Celebration Park was also the title of your show at the Tate in 2006. At the Palacio de Cristal of the Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid, in 2010, you created La Saison des Fêtes, a garden with plants and flowers related to the main seasonal festivities red roses for Valentine’s day, pumpkins for Halloween, cherry blossoms for spring and so on, which you described as “a bouquet of anniversaries.” And again, you shot The Host and the Cloud (2009–10) at the national Museum of Arts and Popular traditions in Paris on Halloween, Valentine’s Day and May Day.

Courtesy of the artist; ; Marian Goodman, new York/Paris; and Esther schipper, Berlin

PH There are different reasons for my interest in celebration. Obviously, it is a time-based pattern, and what I often do is take the form of constructed situations that appear, disappear and reappear over time, looking for a permanence in that intermittence. In order to exist over the long term, even if by intermittence, the work could be attached to these recurring events.

Celebrations are themselves attached to common global tempos, rhythms, timings, whose basis is the earth’s rotation around the sun. I’m interested in the cycle, the return, what Deleuze in Mille Plateaux calls the ritournelle (refrain), this reassurring song that protects you from external chaos. Since culture and technology exist to help common beliefs return and increase, what we have now is a choreography of rhythm to which we dance our lives. I question that cultural pulse, the beat of belief, the conditions of encounter. Rather than focusing on a specific subject, I’m interested in something more abstract, such as archetypes or roles within that beat.

Streamside Day, The Host and the Cloud and La saison des fêtes are about vitality, how a collection of heterogeneous cultural fragments, rituals and display coexist and influence each other without a given script. I have the impression that some artists are working today on problematizing the past by researching, starting anachronic journeys into history, rethinking or taking on the role of the narrator of past histories. With something like One Year Celebration (2008), I was also looking for what we have accepted as common and celebrate, and for the destructive force in the festive.

BC One of your first public projects was La Toison d’or, a carnival, in Dijon. It makes me think of Bakhtin and his definition of the carnivalesque, a literary mode or style that reverses the roles and subverts the rules of expression.

PH Yes, the carnival is a moment where roles shift and reverse, when the fool speaks in the place of the king. For a moment, there is a suspension of power and an immense force of joy and destruction. This is usually celebrated is the dominant language, but one doesn’t necessarily have to comply. Deleuze, in particular, emphasized the crucial importance of that minor language. The Toison D’Or was a situation in which the imaginary of the dominant and the symbol of power were put in an uncertain state. Teenagers wandering in a small park were wearing heraldic heads, symbols of the order of the city, but with no history.

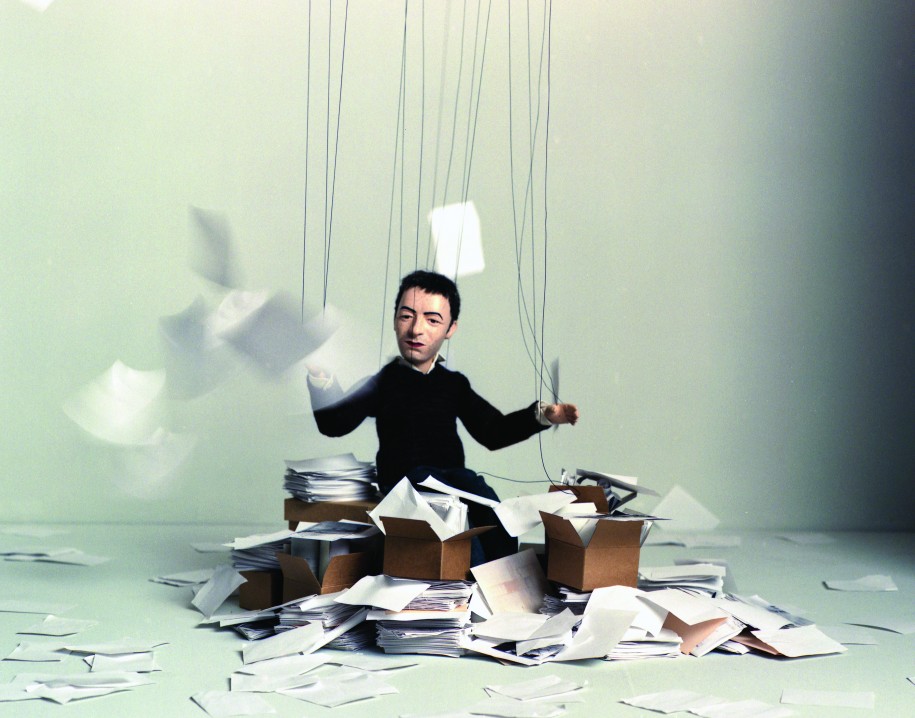

Installation view, "Influants," Esther schipper, Berlin, 2011

Courtesy of the artist; ; Marian Goodman, new York/Paris; and Esther schipper, Berlin

Photography by Andrea Rossetti

BC You have been doing this a lot with cinema. The list is very, very long: we could start with L’Histoire d’un Sentiment (1996, with Philippe Parreno), an unfinished film script with a character whose name was Anna Sanders, which a year later you used for Anna Sanders Film, the production company you two founded together with Charles de Meaux and Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster. Anna Sanders produced many of your films, starting with Blanche-Neige Lucie (1997) and The Third Memory (2000). There was the triple-screen projection L’Ellipse (1998), where you added your own footage to the 1977 film The American Friend, by asking the main actor, Bruno Ganz, to interpret a scene that doesn’t appear in the original movie, thus filling a possible “gap” in the story. And so on… Do you think that cinema became such a strong focus for your generation because of its direct impact on the public? You were born less than twenty years after the end of World War II, in an age when cinema and its rhetoric played a crucial role — just think of Italy, with the creation of the Istituto Luce and Mussolini proclaiming, “Cinema is the strongest weapon.” Then came Neorealismo, Cold War cinema, then Nouvelle Vague, Free Cinema, New Hollywood. And then, finally, home VCRs…

PH The cinema still had a social function, but was already loosing ground to other media more oriented towards the audience’s desire. For a while, I found in novels and films an escape, but at the same time I was looking for something that could address certain concerns more directly; I was looking at fictions, documentaries or experimental films. Cinema was a platform to represent us, to narrate us — you or the society as a whole — through a singular position. Then came the question: Who speaks? Under which protocols? The narrative structures, the ways of conveying something, were very poor and what I had viewed as an escape disappeared.

I have been asked quite often about my interest in cinema. I’m interested in the question of process and displays, roles, action in a public sphere, interpretation, narrative structures, the construction of image, the actor as a contemporary figure. I am interested in the notion of “apparition” under those conditions. What is the role of a person interpreting a scripted text or the one who witnesses it? I listed these interests and realized that, as a whole, they could all fall under a notion of cinema. So I relate to film through these questions.

I also simply used film as a mean to size up a process, and for the possibility of shifting constructed situations that appear and disappear into another time space, translating a live situation from A to B — a site/non-site time-based protocol. so it is always a document of a constructed situation rather than a fiction.

Courtesy of the artist; ; Marian Goodman, new York/Paris; and Esther schipper, Berlin

Photosgraphy by Guillaume Ziccarelli

BC Debord and situationism had a strong impact on your formation, on the idea of a possible détournement of the paradigms of information and mass media.

PH At the same time, Debord problematized the separation of experience, but the experience is now within the separation. I experience a representation, a mediation, as primary matter. But the linear relation — event, image, commentary — can also be reversed.

It reminds me of the commentaries that accompanied images of the war in the 1980s. What I most like most about the situationists is their rethinking of the conditions and incoherences of the encounter.

BC You also organized a pirate television station, called Mobile TV, for the Institut d’Art Contemporain in Villeurbanne, France in 1995 and for Centre d’Art Le Consortium in Dijon in 1997. On the channel, you broadcasted programs involving artists, filmmakers, musicians, architects, philosophers and local residents. You did castings for sitcoms, as well as for Pasolini’s Uccellacci e uccellini, which you then partially reshot (Les Incivils, 1995).

PH Pasolini wrote in Heretical Empiricism that cinema was the written language of reality. So when I look at a film, I look at a text. I thought that by reversing the process that leads from written information to performance, the film would became the score, and I could speak through actions in life. It was a free adaptation of written forms to a live situation.

I then understood a film as a point of departure, not merely a construction of a plot with an ending. The extension would overflow the diegetic world to navigate into differents fields. It is the same way with an exhibition, which for me is not the end of a production, but a starting point or a state in a series of translations. Mobil TV was based on that intuition, so everything became a score to be activated, a zombie, a vitalization of a dead body or a metabolization into something else.

Courtesy of the artist; ; Marian Goodman, new York/Paris; and Esther schipper, Berlin

Photosgraphy by Guillaume Ziccarelli

BC Why do you think Pasolini is assigned such a crucial role nowadays by so many artists?

PH He had an urgent engagement with reality and life through different formats and means. As a poet and writer, he kept his very specific approach to language, even while moving on to different subjects. Language was not only a tool to create or convey political and philosophical issues, but also a means of positioning oneself in relation to others and to life. As a poet, you do not compromise with the language; you can corrupt the language, but in a very precise way. Over the years, what might be important about Pasolini is the attitude and language of urgency he used to confront the society he was living in.

BC My impression is that he has also been assigned the role of patron saint for a collective mourning over the lost role of the engagé intellectual, as well as for the dimension of the political.

PH In Comizi d’amore (1965), he wandered around with his portable microphone among peasants, workers, teenagers, on the street, on the beaches. You see his desire to engage with others, even if it means engaging himself in some kind of absurdity. Although the conditions of the encounter are constrained and unbalanced, there is a sense of equality, a belief in the act of exchange.

Courtesy of the artist; ; Marian Goodman, new York/Paris; and Esther schipper, Berlin

BC Going back to the subject of the public space you started with the artist group Ripoulin Brothers, working on urban signage while at the Ecole des Arts decoratifs, and then your first billboard projects in Paris. The urban sphere was still very much present in films like Les Grands Ensembles (the Housing Projects, 1994-2001) and Block Party (2002, on the birth of hip hop in new York). Are you still interested that dimension, or has it become more abstract?

PH I’m not sure we can call it public space anymore, since it doesn’t seem to exist as such. When I invented a custom for a new town in upstate New York or planted a temporary rain forest in the Sydney Opera House, it was my way of focusing on a relation with urbanity as a place of encounters. I often use the sedimentation of narratives within the site, the site memory, as a language to make the situation appear. It has to do with the physical coexistence of heterogeneous and anachronistic elements of culture.

The recent projects might appear less open — for instance, The Host and the Cloud. that was a live experiment that only 50 people could witness. You don’t necessarily affect the public sphere just because you perform an act in it. I’m not doing things for the public: I’m not a social worker, an activist, a decorator or an artisan. After a series of public events, in which the work could be experienced directly by broader audiences, I’m now more interested in specific experiences with fewer persons, whom I prefer to call witnesses.

BC The aquariums look like small landscapes or case studies.

PH “Case studies” is a good way to frame them. For the aquariums, some rules are set. The conditions are constructed, but the relations between the entities, their behaviors, are real, “natural” and unscripted. It unfolded as a set of operations, an eco-system based on a constructed decision rather than narratives. I’m trying to separate the entities from narratives. In a way, it is a non-illusionistic fiction.

BC It’s the position of God in the Garden of Eden…

PH (Laughs). Someone asked me the same question recently “Are you playing god?” The first time, I burst out laughing. Who is god anyway? I bet the person had no idea of who or what it was that I was supposed to be…

Courtesy of the artist; ; Marian Goodman, new York/Paris; and Esther schipper, Berlin

BC Aquariums are very beautiful to look at, and somehow entertaining. To me, one of the key exhibitions of the last couple of decades was Let’s Entertain: Life’s Guilty Pleasures, curated by Philippe Vergne at Walker Art center in 2000, in which you participated. Looking back on it, do you think one could read the whole idea/business of art and entertainment as a symptom of our times, as something on the verge of disappearing?

PH The aquariums are attractive and distracting, as is life. My hope is that they construct the equivalent of an emotion, a situation the person witnessing it had previously encountered.

Yes, Let’s Entertain was symptomatic of his time, where we are now. As an idea, it has lost its meaning. I remember the context of the exhibition and the kind of fear related to the increase of different media and probably to an overall economic concern about reaching the audience, as if at some point the artists began to accommodate a form driven by financial necessity and based on the dominant language. In order to reach the mainstream, the language of consensus made the entertainment format a way to convey ideas. Alternatively, we could go back to Pasolini, as well as to he who once said, “Un style, c’est arriver à bégayer dans sa propre langue… Être comme un étranger dans sa propre langue” (“to have a style is to be able to stammer in your own language…to be like a foreigner in your own language”) [Gilles Deleuze]. There are different modernities; Michel de Certeau has talked about the absurdity of identifying a mass.

It was obvious that the use of audience desire as an orientation would lead to mediocrity. Some of us grew afraid of being trapped in a dialect, the language of art, the artist as artisan. So rather than go to the consensus, we tried to invent other arrangements that were not driven by the paternalistic language of modern art, the language of entertainment or the dream to reach the masses. I’d rather look elsewhere.