ARCHIVE

PHILIPPE PARRENO

words by Martin Herbert

Courtesy of Pilar Corrias gallery, London

In 2001, Philippe Parreno traveled to a Norwegian island near the North Pole to produce a minute-long film, El Sueño de una Cosa (“The Dream of a Thing”). Despite the artic setting, the climate depicted in the film looks temperate, and at the end a magical mound of vegetation bursts from the ground. If the significance of this fecundity seems subjective and unfixed, the film’s mode of display has proved similarly protean. In Sweden, El Sueño served for three weeks as an anarchic, product-free advertisement, programmed alongside other commercials in the country’s cinemas. In Frankfurt, the film was projected onto Robert Rauschenberg’s White Paintings for four minutes and thirty-three seconds at a time: a nod to John Cage and an explicit reminder that Parreno works in a tradition of questioning the object’s fixity by perpetually displacing and unbinding it, a tradition first explicitly explored in the 1960s.

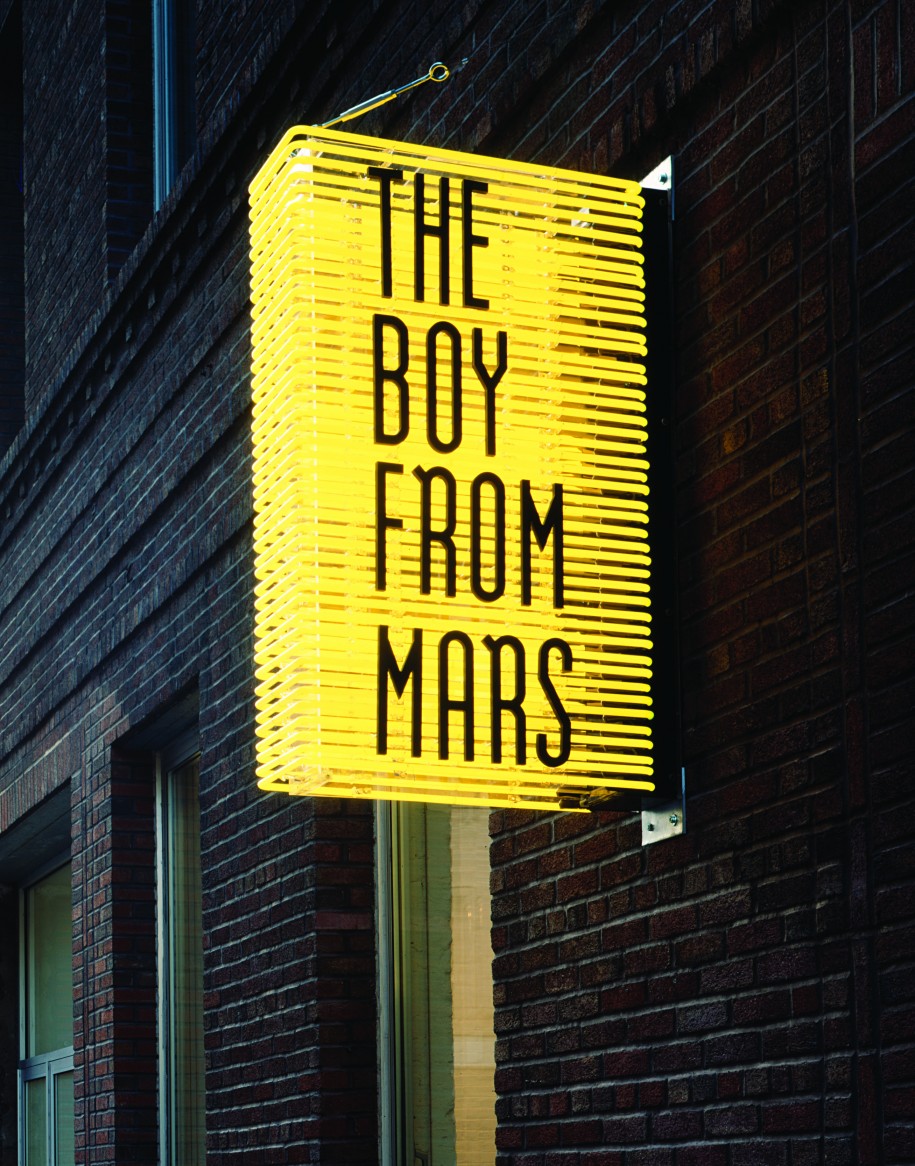

The 1990s saw a widespread resurgence of such explorations. Asked in an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist why this issue won’t die, Parreno has pointed to art schools’ fixation on producing objects, “whereas to me, it’s exciting when the content overflows beyond the form or the other way round. It’s the irresolution that’s interesting.” (In Parreno’s case, it’s perhaps also notable that he has a dust allergy and resists accumulating objects in his daily life.) In any case, his output from the beginning of the 1990s onward comprises a flush of strategies for circumventing fixity. Chief among these is collaboration. Judged alongside coevals, and frequent collaborators, such as Pierre Huyghe, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Liam Gillick, Douglas Gordon and Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Parreno appears most committed to an anti-autonomist practice; indeed, he has worked more with others than alone, with his peers as well as architects, comedians, scientists and television journalists. The most visible—because most permuted—example of this is the work using Annlee, a minor manga character, the rights to whom were bought by Parreno and Pierre Huyghe in 1999. The pair then offered her to like-minded artists to manipulate. By the time of “No Ghost Just a Shell,” the group exhibition of Annlee works which debuted in 2002, fifteen artists had put the melancholic girl through diverse changes; she’d become animations, fireworks, neons, posters—a cipher in a work whose true object was to create a cloud of collaboration and a wholesale deferral of closure.

Courtesy of the artist and Friedrich Petzel gallery, new york

Connectedly, one leitmotif of Parreno’s work is the compulsive figuring of an elsewhere or, at least, a refusal to settle for the here-and-now. The soundtrack for El Sueño, near the North Pole but not partaking of its iconography, was counterbalanced by Edgar Varèse’s Deserts. In 1991’s No More Reality, Parreno had children protest in a schoolyard, demanding Christmas celebrations in September or snow in summer. Eighteen years later, in an October exhibition at Pilar Corrias’s gallery in London, he installed a fake Christmas tree. Unseasonal Christmas decorations have figured repeatedly in works in between: Ice Man in Reality Park (1995) saw a snowman-shaped block of ice delivered to a park every day during summer, while Stories are Propaganda (2005), a film made with Rirkrit Tiravanija, featured a snowman-shaped lump of mud. The same film, shot in contemporary China and starring a red-eyed white rabbit hopping across rain-filled tire tracks in mud, was accompanied by a monologue spoken by a child actor, composed from those excerpts of Parreno’s notes which orbit around a fascination with the world before the early 1970s—specifically, before the end of modernist idealism.

Never quite spelled out in Parreno’s work, but regularly alluded to, is a dream of prelapsarian autonomy that is nevertheless unified under a nebulous larger project. Consider the politicized Warhol reference of Speech Bubbles (1997), for instance, described by Parreno in his monograph Alien Affection as “white Mylar balloons in the shape of cartoon bubbles, made for a trade union. Everyone can mark their own demand, while still participating in the same image.” This is the idealist undertow of Relational Aesthetics and, as that loose grouping increasingly appears historicized—consider museum shows like the Guggenheim’s recent “Theanyspacewhatever”—, it is hard to know how seriously to take it. Liam Gillick, for instance, has carefully distanced himself from the idea that his colorful canopies might really be intended to provoke discussions (about the future, or about anything). They are, he has suggested, more like provocations. Balloons, likewise, were not going to alter the benighted status of trade unions in a neo-liberalist era; cooking a curry for an audience of art world insiders wasn’t going to foment revolution, either. What frequently happened was that everyone stood around slightly awkwardly, never forgetting that this was art: a canny, vaguely nostalgic maneuver, appealing to those who missed the 1960s the first time around.

Photography by Stefan Altenburger

One can further delineate the convenient intersection of aesthetics and pragmatism around a manner of working that either dematerializes the object or makes it into one link in a chain of variations. The 1990s saw the inexorable rise of the biennial and the art fair, which put artists on a treadmill of sorts by demanding that they produce for cultural and economic economies: what better way to ensure you’ll always have something to show than to assert that your work is an endlessly unfinished project, always demanding a sequel? Interactive environments, meanwhile, which take attention off the singular, valuable work—as well as the production of editions in media like video (one of Parreno’s favorite vehicles)—helpfully send insurance and transport costs through the floor. The very idea of an interrelating network of producers, constantly engaged in what Douglas Gordon has called “a promiscuity of collaboration” which reduces the emphasis on the individual artist, seems like a shift in modes of production at the same time as it builds a mutually beneficial support group: one that, aided by theorist/curator Nicolas Bourriaud and the curators of Dijon’s Le Consortium in particular, dominated the 1990s.

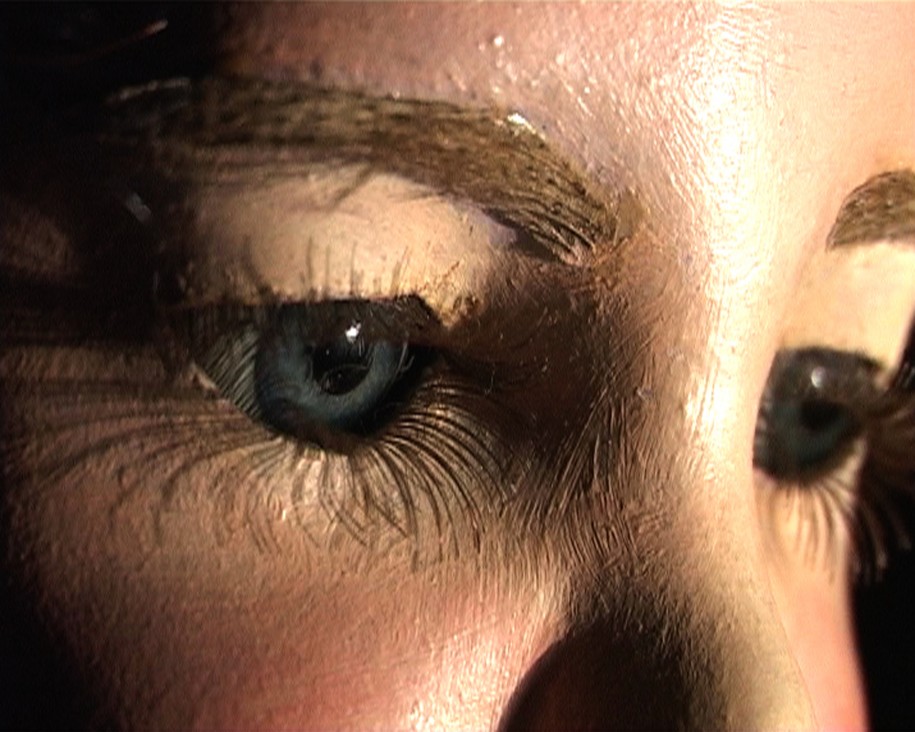

And yet Parreno’s work feels sincere, romancing ideas and possibility and unexpected upshots. His multi-venue retrospective this year, which will be hosted at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Kunsthalle Zurich, the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin and Bard College in New York, circumvents the fixity usually yielded by such an occasion. Indeed, it reverses the usual terms of a retrospective, projecting itself into an uncertain future as much as it replays the past. The Pompidou’s segment involves, among other things, an invitation to children to put on performances inspired by his past works and a variation on his earlier speech balloons. Zidane: A 21st-Century Portrait (2006), his film produced in collaboration with Douglas Gordon, which trains 17 cameras on footballer Zinedine Zidane during one 2005 match against Madrid, feels like it was made in the cognitive dark. It arose, Parreno said later, out of a childhood desire to know what one’s televisual heroes were doing when the TV was switched off; and it ended up being both an extension, in classically Parreno style, of something already existing (the televised match) and a deep study in enigmatic character.

Courtesy: the artist

Meanwhile, first shown in Manchester in 2007 and most recently at Art Basel last June, “Il Tempo del Postino,” Parreno’s joint venture with Hans Ulrich Obrist to mount a group exhibition onstage—one whose guiding factor is not space but time—conceals genuine intellectual curiosity under its spectacular, attention-seeking veneer. The idea of a show that “delivers” its work to an audience, and determines the duration of their engagement, has deep roots for Parreno: his 1994 performance-based work Postman Time/Facteur Temps (of which “Il Tempo del Postino” is the Italian translation) involved a postman handing out flyers and leaflets to strangers and engaging them in conversation. Parreno’s contribution to “Il Tempo…” was entitled Postman Time and was performed by an onstage ventriloquist. His video The Writer (2007) featured a mechanized puppet laboriously programmed to write the phrase “What do you believe / your eyes or my words.”

Working with imitative stooges and throwing one’s voice are obviously extensions of the collaborative process. They speak, like Parreno’s decision to operate predominantly within pairings and groups rather than alone, of an essential modesty: a dispersal of authority related to his art’s pervasive openness to interpretation and resistance to concentration in singular, masterly works. Despite that diffidence, Parreno appears like the éminence grise of the loose-knit group of 1990s artists of which he was a part, many of whose ideas and tropes first glimmered in his works. If art, as seems likely, is headed toward its dissolution into other media like cinema, architecture and music, the necessary preparatory stage is for the artwork to lose its singularity, to advertise its mutability. Nearly two decades ago, in Parreno—who claims to see no difference between books, films, artworks, etc., insofar as they are producers of intensities—such a development found an outrider.