ARCHIVE

MICHAEL CLARK COMPANY

words by Catherine Wood

Photography by Jake Walters

In a square of white light projected onto the floor, a male dancer knots his body into angular shapes: arms rigid, fists clenched, and head to one side. He curves forward through his back to assume what looks like a stretching position, holding his legs beneath bent knees, but pauses only for a split second before rolling again, one crooked leg pressing to the floor against the direction of his torso. Set within the opening moments of Michael Clark’s project for Tate Modern, part I (2010), the continuous unfolding of movement in this sequence makes it hard to quantify its compositional elements as discrete units. Each movement is exquisitely unpredictable, truncating our expectations for the movement phrase that it begins. There is a cubist quality to the dancer’s striving to fully inhabit the space marked out by the flat white square on the floor, pressing his body’s surfaces to the ground, at times into near impossible contortions. But to think only of analytic cubism’s geometries detracts from the work’s extraordinary emotional intensity. The choreographed exposure of the dancer’s body—set to the charged strains of David Bowie’s Sweet Thing—is almost painful in its intimation of psychological restlessness, as though the dance is a search, without apparent end, for a still place to be.

O (2005), the first work in Clark’s recent “Stravinsky Project,” (completed 2007) opened with the image of a single dancer inside a mirrored cube. Like the patch of white light in part I, this image summoned the enclosed space of the studio, nodding reflexively to the solipsism of a dancer’s, or an artist’s, endeavor. By proposing an image of the studio as part of his performances—the wooden ballet barre also features in recent work—Clark challenges performance’s necessary publicness (and the inevitably social aspect of choreographing for a company), exploring the aspect of learning and making dance that is a fundamentally private activity. In fact, one of the most compelling things about Clark’s work is the sense that it derives from an inner and innate impulse towards movement.

At first, I understood the daily theater of the Michael Clark Company studio, relocated to Tate’s Turbine Hall during their seven-week residency, as a revelation of process. Looking at the broken-down steps and phrases performed often at walk-through speed brought me to a new understanding of Yvonne Rainer’s famous statement from the 1960s: “Dance is hard to see.” Through the warm-up, daily classes (Cunningham or ballet technique), and rehearsals, the lexicon of physical movement and training of the dancers’ capacities, which are often spectacularly subsumed by the speed of changing form onstage, were demonstrated with new clarity.

But if the entirety of Clark’s work is taken into account, the notion of “process” is fundamentally inadequate to describe what is happening when we see his choreography’s mechanics laid bare. Process art in the 1960s or 1970s involved actions, usually repeatable and often not requiring skill, that constituted the principles that had brought an object into being. A key example was the action painting of Jackson Pollock, and his treatment of the canvas as “an arena in which to act” via his famous drip technique. The process art object was not necessarily the principal focus of the work, but its outcome, understood as having an almost accidental status.

In Clark’s work, it is not process, but the less fashionable—or more old-fashioned—notion of practice that is key. This factor, a staple of his daily approach to making dance, is at odds with the popular image of Clark as a rebel, a “dance anarchist.” Clark’s residency, and its revelation of the rigor of his company’s daily regime, made me think about the deeper issue of a studio practice—that is, a form of making that involves returning to the same space, the same rituals, the same practical exercises on a daily basis, to serve the upkeep or development of a skilled form or language—and what studio practice means for artists today.

Practice is a notion familiar to dancers, painters, and classical musicians. In contemporary art terms, studio practice has been significantly challenged on two levels in the past fifty years. Firstly, by Andy Warhol’s notion, beginning in the 1960s, of the studio as a “factory,” with its refutation of the importance of individual skill and adoption of a model of production borrowed from industry (an attitude spectacularly mimicked by Jeff Koons, Takashi Murakami, and the like in later years). Secondly, through a position associated in the 1970s in the USA with conceptual artists such as John Baldessari and Michael Asher on the West Coast of the US, and their famous “post-studio” program at CalArts. Since they— like many other conceptual artists of their generation—were making art out of ideas (“Work that is done in one’s head,” as Baldessari put it), which might pop up at any time, the physical space of the studio, and the repetitive ritual of making that studio practice implies, was seen as irrelevant for that kind of work.

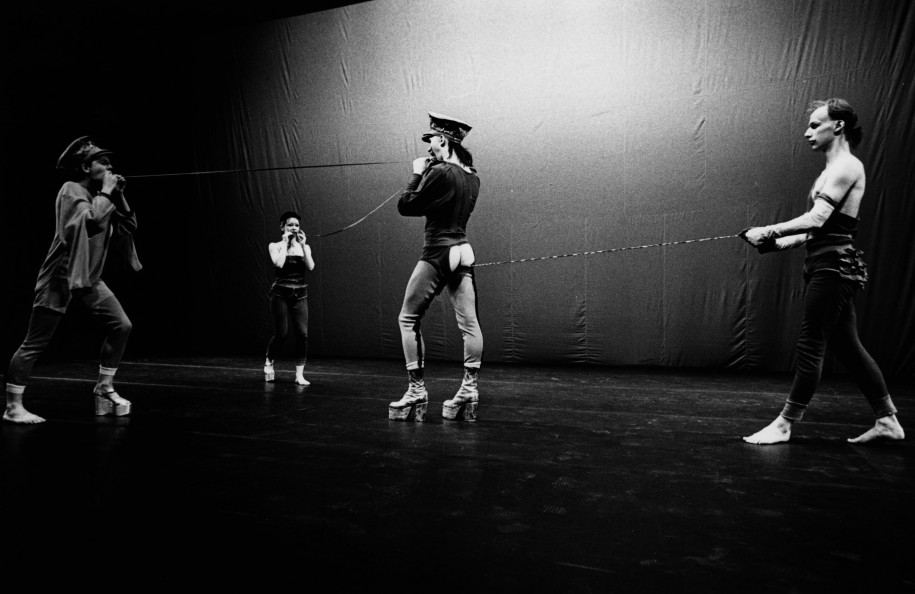

Early on, Clark’s work made visible, often satirically, the clash of worlds between the refined space of the ballet academy (he trained with the Royal Ballet) and his ordinary life outside of ballet, crossing over into the post-punk 1980s scene. The Charles Atlas fantasy documentary, Hail the New Puritans (1984–85), splices footage of Clark’s choreography, featuring dancers in cheeky butt-cheek-revealing leotards and face paint, with Michael and friends (notably, Leigh Bowery) attired in outlandish costumes, dancing in a club or walking London’s grimy streets. In the film, London’s Chisenhale Dance Studio is re-cast as Michael’s loft apartment, and through Atlas’s playful vision, we see him practically dance his way out of bed before joining in a group routine.

Photography by Hugo Glendinning

Such an idea of the blurring of art and life was a playful one—and one that Clark, too, has drawn upon in his choreography—but the film’s irreverent subcultural exterior masked Clark’s truly alternative approach to the notion of art’s embeddedness in the everyday. Although the studio connotes a sense of remove from the outside world, from everyday life—whether from the ordinary movements of walking or running or carrying things that Steve Paxton, Rainer, or Simone Forti put on stage in the 1960s, or indeed from the dance moves of the 1980s nightclub scene—practice accumulates as a facility that becomes rooted in the practitioner’s body; as a manner of being. While Rainer conceptualized the mind as a muscle in deadpan terms, attempting to submerge the anxiety of analytic thought in straightforward physical activity, Clark’s dance practice is grounded in a ritual that pushes the movements it incorporates into a space that precedes thinking. For the artist, this means that the daily repetition of the studio is taken for granted prior to thinking about what to do and what to make. In other words, creative process follows from physical training and physical capacity. Such pre-conscious immersion in a discipline is the opposite of Baldessari’s self-aware and witty video showing himself assuming a series of different positions, I am making art (1971), or indeed from Ryan McNamara’s recent work, Make Ryan a Dancer, in which McNamara “tried on” a wide variety of dance styles, from hip-hop to salsa to striptease, throughout a three-month period. The practice of going through the same motions repeatedly lends the practitioner a different form of art-into-life: formal fluency. For Clark and his dancers, the discipline of dance is assimilated through their bodies to such a degree that the learned forms and movements are a part of the dancers as a latent, organic capacity, even when they are walking down the street.

The first of Clark’s pieces for the Turbine Hall was choreographed to Kraftwerk’s Hall of Mirrors. His dancers, dressed in black workout clothes, stepped across the space in diagonals lines, pacing forward on the beat but languidly dragging one foot behind them. The dancers carried deadpan demeanors. Doll-like, their limbs seemed to swing as though hinged from the shoulder or hip, yet their arms occasionally arced in the air with extraordinary lightness, before bodies slackened at the knees, forcing their stiffened upper bodies into tilted slants. The movements, like Kraftwerk’s music, owed much to the readymade industrial forms of the 20th century: the repetitive sounds and motions of factory machinery or workers, an aesthetic very much at home in this former power station.

But as my distinction between practice and process attempts to make apparent, Clark’s mode of production has as much to do with industrial modernism as with the emblematic status of folk dance within a close-knit community. Towards the end of Hall of Mirrors is a part of the music that sounds like the electronic equivalent of pealing bells, calling the inhabitants of a village to prayer. In Clark’s community of dancers, the figures spin, turn, step, and jump in dynamic configurations, sometimes mirroring each other, but always with just enough asymmetry. There is an incredible thrill to this apparently disparate but entirely coherent and choreographed group activity: an intricately plotted transposition of the unformed mass of a crowd milling in a public square.

Photography by Chris Harris

Writing on the “entanglement of the gestural and the political” in Giorgio Agamben’s Notes on Gesture, Dieter Roelstraate observes, “In favouring interiority (‘content’, personality, psychological states) over exteriority (‘form’, exchange, propriety), contemporary society not only strikes us… as formless and disorderly on a purely political level, but ultimately also as a rather uninspiring, uncouth mess, divested of all sense of ‘theatre’, and with very little opportunities left for the nurturing of various artful ways of living.”1 Clark’s Hall of Mirrors poetically counters this impression by grafting the meditative introspection of the dancer in his or her mirrored studio —the space of interiority—onto the vast public scale of the Turbine Hall, connecting the pre-consciousness of practice with the outward expression of gesture as a form of public life. Set in the center of a crowd gathered around the edges of the Turbine Hall’s planed floor, his choreography created an extraordinary compression of the pedestrian activity to be found there through forms of movement that occupied a different order of space and time. The movement in the work packs infinitesimal detail into the execution of each sequence and each transition, and the resulting work appears as a hallucinatory refraction, re-imagining ordinary activity through the palpable expression of the dancers bodies, seen at close hand. Taking a cue from Roelstraate’s observation, Clark’s approach to practice offers an evolution of the blurring of art and life by “nurturing an artful way of living” and, so, working form into the disorder of reality.

Photography by Jake Walters