ARCHIVE

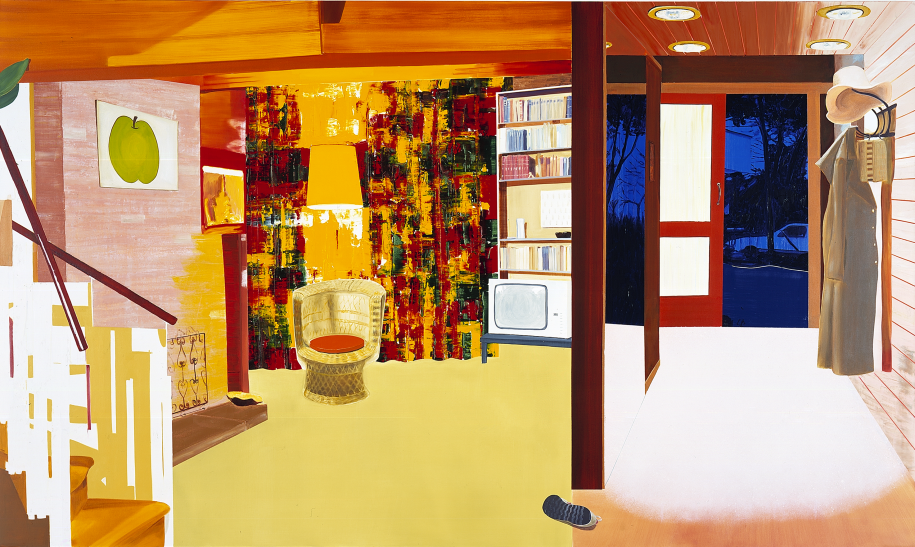

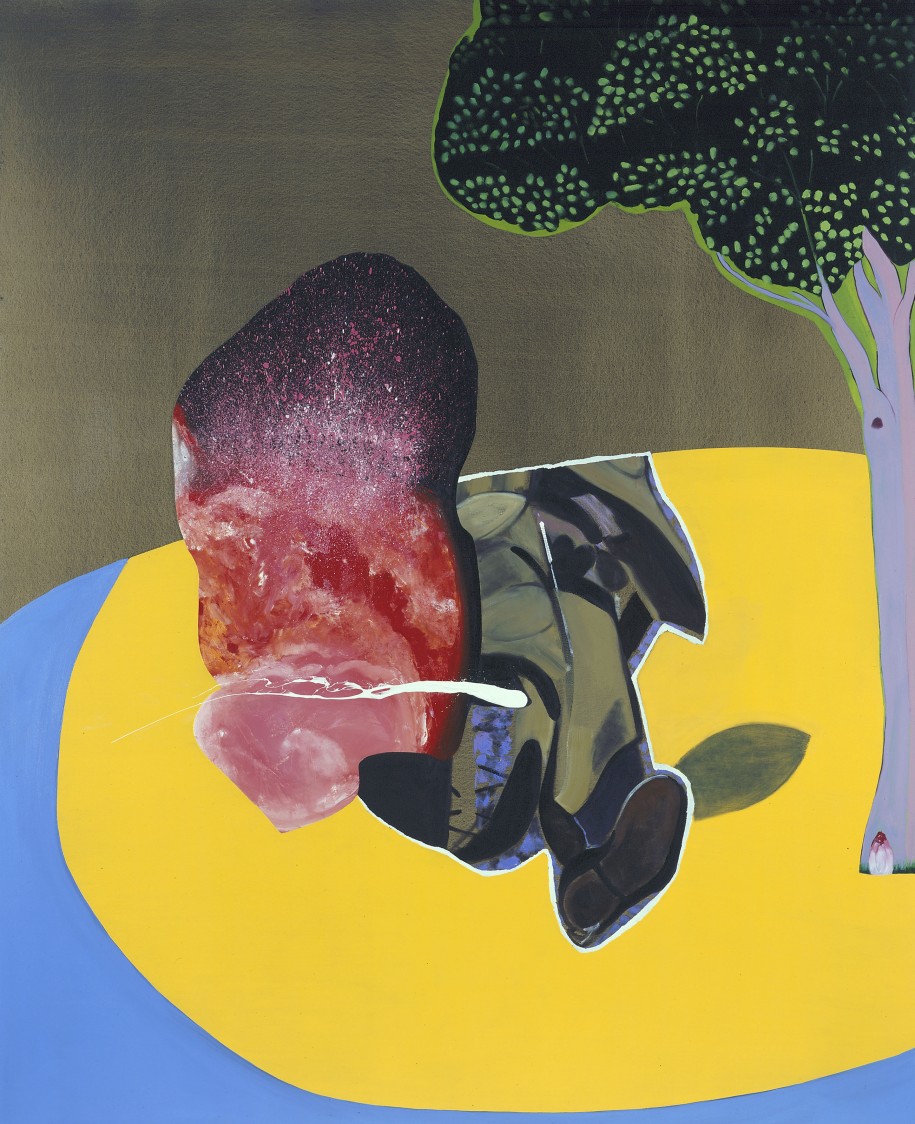

DEXTER DALWOOD

interview by Cherry Smith

Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery

CHERRY SMITH Your paintings are a marvelous negotiation of the facts and fictions of history. Do you remember the first time you realized that history wasn’t the same as truth?

DEXTER DALWOOD My father was a bookseller and I remember finding a book with pictures of Belsen. It’s one of those things you can’t really explain—any sort of innocence is lost. You can’t fathom it as a child, although you can have an inkling of it when you’re an adult. We used to watch the news a lot. My mother was fascinated by the Nixon trial. I remember watching that and thinking it was a really big thing. I was always thinking that there’s this dark underbelly of the world; everything isn’t quite as it seems.

CS What was your first counter-cultural involvement?

DD I was in a punk band, The Cortinas, in Bristol. We signed a record contract and made a few singles. I saw the Sex Pistols in 1976 and my whole world took off. But it did end very quickly! By the end of 1978, I was disillusioned with it.

CS Did you ever study graphics?

DD No. I left school after a year of A-levels and got a job in a foundry doing bronze casting. I got into art in a mad, enthusiastic way. I did five evening classes a week and went to Saint Martin’s when I was 21. I thought I wanted to be a sculptor. But I didn’t like what was being taught in the sculpture department, so I got into Beckmann-esque figurative painting instead.

CS Have you even doubted your faith in narrative and tried abstraction?

DD I did bad semi-abstract paintings for while at the Royal College of Art. I remember reading Dore Ashton and admiring Guston’s rejection of abstraction and his idea of how an artist should be connected with the world. I identified with his desire to be connected not only with the history of painting but with political reality. But what I came to doubt with figurative painting was the notion of the viewer identifying as the protagonist. It feels like nineteenth-century theater. I’m more interested in making viewers think and think about how they connect paintings to the past and how they construct something that isn’t being depicted in the painting.

Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery

CS How do you keep statement to an understatement and keep didacticism out of your use of satire and irony?

DD Often I brainstorm the original idea to get beyond the obvious to something that isn’t illustrative. It always takes a while for it to settle into a fragmented and mythic version of something. I started to realize that quoting other painters—like citing a Clyfford Still in Brian Jones’ Swimming Pool—was another way of avoiding heavy-handedness. I was really interested in how presenting an artist’s work in another context changes the way you think about that artist.

CS How would Clyfford Still feel about being quoted in this way?

DD He’d hate it, absolutely! But I’m fascinated by his hubris and by how the Titans of art go up and come down. Art history is as cyclical as history; reputations do go floppy. When I was in college in the 1980s, the teaching in the painting school was still very pro-Abstract Expressionism and now, after the rehabilitation of Warhol (who wasn’t taken seriously then), we are somewhere else. His effect has been enormous as part of the cycle of reappropriation. I am interested in making the viewer think, “Is this passage of paint a redundant bit of ideology, or is it something that makes me rethink the whole thing in a new context?”

CS How you position the collaged elements and scissored edges amid traditionally “painted” visuals amplifies the constructedness of images, of aesthetics, of culture. Is collage, which was highly subversive when used by Hannah Hoch and Martha Rosler, in danger of becoming worn-out and over-used?

DD I was talking to Alan Cristea about a Richard Hamilton print of a collage from 1969, and I was saying that the reason why it was interesting then was because the screenprint with the collaged bit looked like a screenprint with a collaged bit. Although you could achieve that “look” today with Photoshop and digital printing…

I’m more interested in getting back to Burroughs’ idea of jamming together different elements and making them work. Collage can’t just be arbitrary. It has to become more than the sum of its parts.

Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery

CS You’ve called collage “the engine for the painting.” How does a collage become a painting?

DD I use the collage as a template for my paintings, but often the colors and focus change. The whole point is the invention of the image through the found image. Then the painting itself is quite controlled.

CS In recent work, like the death of David Kelly, the painterly quotations of Yves Klein and Lucas Cranach seem more embedded in the work than when you quoted artists like de Kooning or Morris Louis in earlier works. It works immediately on a powerful emotional level.

DD That painting surprised me, and it surprises me that it has become the painting that people seem to respond to most. It’s a bit like writing an album and having the hit be the song you weren’t expecting. I’d thought about the painting for a long time, and wanted this massive field of color to work with the intensity of an Indian miniature.

CS The title outwits the viewer, defying our expectations, too. You must always be negotiating how much to reveal the painting’s intentions in the title.

DD Yes, and I’ve also not wanted to reduce the painting for the sake of the title. My other fear is that I will distill and distill until the work doesn’t mean anything anymore. Originally, I was faced with the problem of being a figurative artist and answering the question, what do you paint about? You have to keep the possibilities open so that you can maintain the excitement. It feels like you’re dragging a trolley of cans behind you—the everyday, history, and all the things you like. I’m excited by perversity: I love it when artists do something about a country they don’t come from. Like Karen Kilimnik’s painting with a girl behind a car window called Me - I Forgot the Wire Cutters - Getting the Wire Cutters from the Car to Break Into Stonehenge. Fantastic!

Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery

CS Your work has the coolness of Patrick Caulfield, but is much more politically engaged and exuberant. Is the legacy and label of British Pop more of a burden than a stimulus? Was Sigmar Polke and Gerhard Richter’s german pop as much of an influence?

DD Perhaps Bacon is more relevant. He’s a case in point of changing reputations: in another fifty years, we’ll view him in a completely different way. His work will become more to do with the sensibility of the King’s Road in 1972—Peter Jones’s shop windows, etc. But I think of Bacon as more connected to Caulfield than someone like David Bomberg. The reflective loneliness of Caulfield’s interiors. Not just the physical interiors. The sense of ennui. Caulfield’s work is quite amazing, and he would have been a much bigger artist if he’d been born in a different time. There’s none of his work in any American collections. Sigmar Polke came to painting through performance and jokey installation. Then he made jokey paintings and kept painting. I like the freedom of that compared to coming through the mangle of an English painting school. It reminds me of that Stanley Spencer quote that every time he tried to draw a figure after the Slade, he felt he had contracted some sort of virus. You get into a way of doing something at art school that isn’t particularly your own, but you think it is—it’s in the air—and you have to push beyond your own taste, as Lichtenstein put it. You have to up the ante.

CS Who was the first artist you saw who made you think, “I want to do that!”?

DD I don’t think there was one. My uncle, Hubert Dalwood, was a sculptor. He was quite successful and he died very young. I used to go to his studio. Seeing the Guston show in the Whitechapel in 1981 was a big turning point, particularly seeing the documentary film of him, which made me think I wanted to go “deep in” as a painter. I then saw it again twenty-four years later. Although I thought it was gospel when I saw it as a student, this time around, I thought, “Oh, I don’t really agree with that,” or “That’s a bit sentimental.” I was always just as interested in walking around the National Gallery as seeing contemporary work.

CS I love how you can evoke cultural memory without nostalgia. It’s tough and enlivening and allows viewers to experience certain co-existences with their own past.

DD The idea that a painting is expected to function exactly the same for everyone at the same time interests me. Why would it? It’s intriguing how you perceive what you’re doing, what you’re actually doing and what people think you’re doing. It’s incredibly complicated and often not at all recognized. Historically, there’s an idea of bad painting, which came into the vocabulary after the “Bad Painting” show at The New Museum in New York in 1978. Artists like Martin Kippenberger and Francis Picabia were attached to the idea that the shift in aesthetic from the “bad” to the good would allow one to reappraise the intelligence of what viewers are looking at and what they are thinking about, according to the cultural context.

Now, the importance of context is a given. For me, it’s about the associations rippling out. There’s still an expectation in visual art that everything must be immediately readable. I want people to go further than what’s first readable.

Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery

CS At a time when there’s so much pressure to see political art as participatory, do you feel that the role of the political painter is an embattled one?

DD I don’t feel embattled! It’s important for me that I don’t become one thing. I like to mix up the significant with the insignificant. I don’t want to be bombastic; I want to visually nudge. I got an email about the David Kelly painting from a surgeon who is campaigning to reopen the investigation into Kelly’s death. No one has ever committed suicide from an ulna artery being severed. So he thanked me for bringing Kelly’s death back to public attention. It really made a difference. But I also can’t kid myself that it really makes much of a difference to anything. I remember doing a residency in India in 1986 and lots of the students were staunch Marxists, so it made me think on my feet. It’s very interesting to be around committed people and think about what it means to be an artist and whether there is such a thing as artistic responsibility.

CS Like Auden said, “Poetry makes nothing happen.” But no one quotes the remainder of that poem, in which he writes, “It survives in the valley of its making… A way of happening, a mouth.” The action in the body and out of the body makes it valid.

DD Yes, poetry became important to me in my late twenties, and yet there’s the problem of it— the solitary nature of it between you and the page, and the excitement of it, which is almost impossible to convey.

CS What contemporary painters do you admire?

DD I thought Luc Tuymans’s early work was very interesting, and I loved the Raoul de Keyser show at the Whitechapel. Vija Celmins’s early work. George Condo and Gunther Forg. And I really admire the consistency of someone like Ed Ruscha, who has been asking the same question of visual material since he was twenty-two. I don’t really like group painting shows, however. I prefer it when painting is juxtaposed with other genres in a dialogue—something that sadly doesn’t happen enough.

CS What keeps you painting?

DD Believing that it’s important to sharpen the intelligence that is part of looking and to get the next generation interested in painting. A lot of people will see the Turner Prize show and maybe a fifteen-year-old from Salford will see it and be inspired.