ARCHIVE

155 FREEMAN

interview by Chris Wiley

CHRIS WILEY To begin, can you each describe the impetus behind your projects, and how they first came about?

LIGHT INDUSTRY Light Industry began in 2008. At that time, we were thinking about how New York is fortunate to have so many fertile communities devoted to cinema, or the art of the moving image more broadly imagined — experimental film and video, the visual arts, the academy, documentary, new media, and the more adventurous channels of international feature filmmaking, to name only a few — but for a number of reasons, these worlds have had much less social overlap than one might expect. So we conceived of Light Industry as a kind of crossroads between these different concerns, a place where one might, say, see a Straub/Huillet film one week, a performance by Cory Arcangel the next, followed by a Branden Joseph lecture the following week, all appearing on the same calendar. This calendar, then, would implicitly propose an argument that these works might all gainfully be thought of as forms of cinema, as a way of mapping out its many permutations in the 21st century.

We also set out from the beginning to have our venue in Brooklyn, which then felt underserved by the kinds of programming we wanted to see. Our space for the first two years was in a converted factory loft in south Brooklyn, with sweatshops, a cardboard box factory, and a manufacturer of artificial flavors all in the same complex — light industry in a more literal sense!

THE PUBLIC SCHOOL The Public School is an open-source educational program founded in early 2008 by Sean Dockray and the Telic Arts Exchange in Los Angeles. In 2009, with the help of the New York Prize Fellowship from the Van Alen Institute, Telic and a local architectural collaborative, common room, founded the Public School (for Architecture) New York. In 2010, the school’s committee voted to remove the subtitle “(for Architecture)” in order to open TPSNY to more diverse audiences and interests. Since then, chapters have opened in cities across the world including Berlin, Brussels, Durham, Helsinki, Philadelphia, and San Juan. Each chapter functions independently yet stays in keeping with the original mission of being “a school with no curriculum.”

Most importantly, The Public School provides any curious person with access to an underrepresented educational model. Our classes are free and organized by participants; people who may lack access to the university system can partake, while the collaborative learning process undermines the hierarchy of authority that holds sway in an accredited classroom. Each school tries to engage with its community by allowing the public to propose, design and teach classes. A rotating committee of volunteers helps organize and facilitate the discussions. Active participants of The Public School are recommended and welcomed to join the committee and help schedule classes.

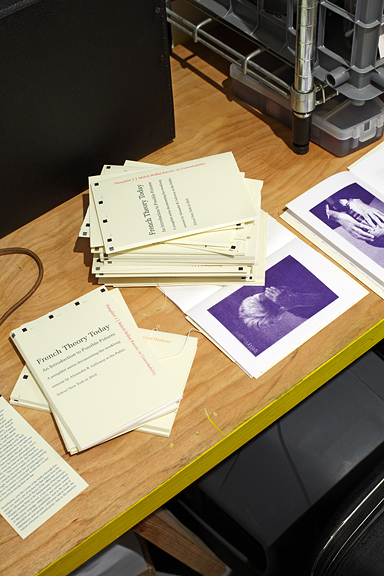

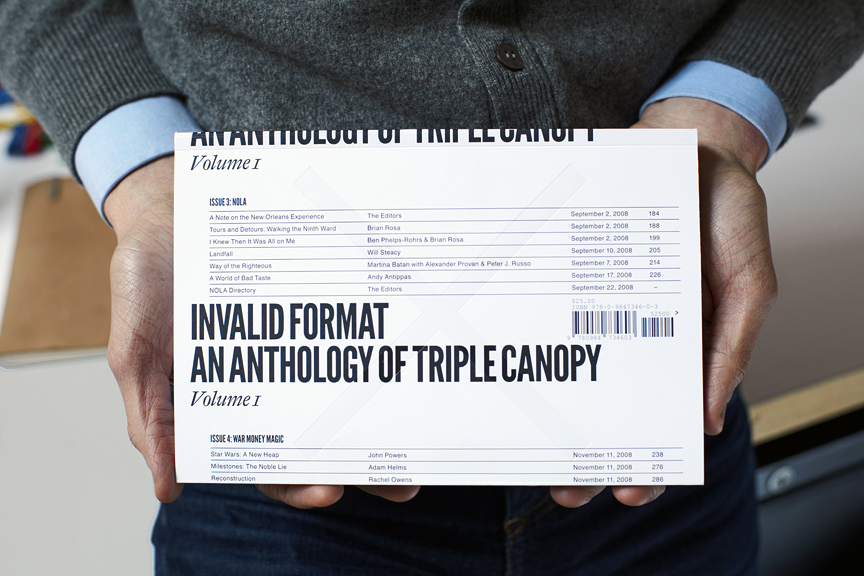

TRIPLE CANOPY Triple Canopy began in 2007 as a group of twenty or thirty people — writers, editors, artists, designers, academics, technologists — who were interested in working together to start an online magazine but had determined little else about the project. We emailed and talked and emailed for six months or so, sketching the contours of the project, establishing our interest in exploring what we call the “expanded field of publication,” before beginning to publish. Now we run an online magazine but also publish books and artist editions, organize workshops and discussions, do teaching residencies and participate in exhibitions. The basic idea has been there since those early conversations: We want to engender a new culture of reading and viewing on the Web; “slow down the Internet,” as our mantra goes, working with and against the constraints of the medium. And we take our approach to working online into print and public programming, producing broadsheets and editions and twenty-four-hour readings and theater.

CW Each of your projects springs from seemingly disparate sets of concerns. Can you talk about how you came to share a space, and what you view as the commonalities between your endeavors?

TPS Our three organizations previously shared a donated space in downtown Brooklyn for ten months in 2011. When the lease was terminated, each organization operated itinerantly while searching for a new space to share. Meanwhile, The Public School website and its community collaborated with Light Industry and Triple Canopy to become a platform for educational and participatory programs such as “Tektite Revisited.” The collaboration continues in our new space at 155 Freeman.In both spaces and other temporary venues, it is important for us to recognize our commonalities — pursuing rigorous, intellectual, creative pursuits; engaging various publics — while remaining independent in our own identities. We say “155 Freeman” as shorthand to refer to ourselves collectively in the space, but there is no actual fixed 155 Freeman entity.

The Public School New York continues to work with other organizations and spaces, and occasionally at external public spaces like 60 Wall Street where we held the “Learning from Occupy Wall St” classes this past fall.

TC All three organizations were founded around the same time; since the beginning we’ve been interested in each other’s work — and in need of our own spaces but unable to afford them. We’ve also been excited about the possibility of giving our respective projects multiple lives and audiences via a Triple Canopy article reflecting on a Public School class that was inspired by a Light Industry screening, for instance. (Also, Caleb Waldorf, a founder of the Public School Los Angeles, is a co-founder of Triple Canopy and the architect of the magazine’s Web platform; in November 2009, Triple Canopy’s Sam Frank organized a screening of Wang Bing’s 14-hour film Crude Oil with Light Industry.) Though our mediums differ, we all share the desire to reanimate and revise a set of conventional models: the artists’ publication, the little magazine, the cinematheque, the alternative space, the pedagogical collective.

In the summer of 2010, Triple Canopy and The Public School and Light Industry took over 177 Livingston, a five thousand square foot ground-floor storefront in downtown Brooklyn, for nine months. Then we began the awful year-long process of looking for, and then waiting to move into, 155 Freeman.

LI Aside from being able to throw much bigger parties together, sharing a space has been very successful in terms of creating awareness across our different audiences, which from our perspective is a natural extension of Light Industry’s original mission. And as mentioned before, there has been some crossover in terms of members of each group as well. People from Light Industry and Triple Canopy have served on the steering committee for The Public School, Triple Canopy members have presented shows at Light Industry; both of Light Industry’s directors have written for Triple Canopy, and so on. All in all, it’s been very inspiring to work together.

CW How do you see yourselves fitting in the history of alternative spaces and non-profit initiatives in New York, and how do you think you deviate from previous models?

TC For us, having a public space where people can assemble is a clear extension of our publication practice, part of a feedback loop in which projects are conceived, discussed, executed, published, picked apart, revised, republished in another form, etc. Of course, there are plenty of magazines that have been organized as alternative spaces, and spaces that have published some representation of what they were up to. Avalanche, for example — the art magazine published by Willoughby Sharp and Liza Bear from 1970 to 1976, which hosted screenings and performances in its lower Manhattan office. While much of what we publish online is particular to the Web, it mostly emerges from — and, ideally, feeds back into — interactions between people in real space.

Oh, and just like alternative spaces in the ’70s, we need a place to drink whisky and have meetings (it cuts down on the emails).

LI We see ourselves as existing very much in a tradition of intrepid New York film spaces, from Amos and Marcia Vogel’s pioneering film society Cinema 16 in the 1940s and ’50s, to Jonas Mekas’s Filmmakers’ Cinematheque in the ‘60s, to the Collective for Living Cinema, which began in the 1970s and ended in the early ‘90s. In fact, we began discussing what would become Light Industry while Ed was delving into the Collective’s archives, doing research for an article on Orchard Gallery’s retrospective exhibition about the organization; looking at that history definitely influenced our early ideas about Light Industry. Our board includes Jeff Press, one of Orchard’s founders and a former Collective board member, and Brian Frye, who ran The Robert Beck Memorial Cinema, a seminal microcinema on the Lower East Side that began in the late ’90s. However, while we’re inspired by these early models — the Vogels’ catholic view of cinema, Mekas’s indefatigable energy, the Collective’s intellectual rigor — we see Light Industry not as an exercise in nostalgia, but rather a rethinking of what cinema can be in the 21st century and an exploration of how this tradition can move forward.

TPS Some of our programming engages explicitly with the history of alternative education in New York and beyond; we recently had a class that investigated new models of autonomous, alternative, accreditation, and we have an ongoing series with Hollow Earth Society engaging with topics of para-academia. One of our strengths is our ability to flexibly collaborate with individuals and groups. A current example is “#whOWNSpace GREENPOINT: Observe, Diagram, Intervene” which was the second in a series of design studios. The series is organized by DSGN AGNC, DoTank:Brooklyn, BRUNO, 596 acres, Not An Alternative, and The Public School New York. Our impetus is to introduce design as a tool for activism and intervention in urban communities. The Public School New York is specifically not nonprofit or for profit, and operates almost without a budget. A different learning experience emerges when ideas are exchanged without being monetized. This model thwarts the expectation that a learner will passively receive information like a purchased good handed over the counter. We hope that in our classes participants’ preconceptions of a topic (including those of the discussion facilitator) will be complicated by the multiple perspectives that are shared.

CW What are the upcoming events at 155 Freeman?

TC In the coming weeks and months, Triple Canopy will host a performance by artist Anna Lundh; a conversation with writers Gabriella Coleman and David Auerbach about the culture of anonymity and the politics of hacking; a discussion between scientists and artists about the usefulness of neuroscience as an interpretive framework; the U.S. debut of a new composition by the free-jazz trio Dawn of Midi; as well as several off-site projects including conversations on the nature of publishing at MoMA with artists David Horvitz and Sarah Crowner and poet Ariana Reines (which will lead to the production of a related publication) and a series of workshops with artists and writers based in Sarajevo co-organized with the nonprofit NO(W).

LI In a couple of weeks we’ll be hosting an event with D.A. Pennebaker in conjunction with MoMA’s Documentary Fortnight. He’s going to present an extremely rare screening of Elizabeth and Mary (1965), a direct-cinema portrait of two twin girls, one of whom is blind, one of whom is partially-sighted. Though he considers it a personal favorite among his own films, the work has been largely unavailable for public exhibition because it was commissioned as a medical film. Later on, we’ll be presenting Jean Grémillon’s noir-melodrama Pattes blanches (1949) and Sara Gomez’s posthumously-completed, fiction-documentary hybrid De cierta manera (1978), a key work of post-revolutionary Cuban cinema.

TPS Dark Nights of the Universe, a four-night theoretical exploration of mysticism in dialogue with Du noir univers, a short text by François Laruelle. It will take place from April 26–29.