WEB SPECIALS

THREE POSITIONS ON THE ART OF DAMIEN HIRST

words by Isobel Harbison, Laura McLean-Ferris and Carson Chan

Photography by Maggie Jones

MORE BOOM THAN DOOM by Isobel Harbison

Hirst is a modern hero. It’s true. He will go down in the history books, or virals, or whatever format history books will take once we are all consigned to its oblivion. It doesn’t matter whether or not the works mean anything, that’s not the point. In an age when, in Mark Fisher’s terms, “all that is solid melts into PR,” Hirst has found the magic formula to transform PR into something concrete. And if that’s not art, then it’s certainly artfulness. What’s interesting about the recent Hirst retrospective at Tate Modern is neither the individual works, nor their presentation, but rather what the success this work represents culturally: art’s convergence with the culture of branding.

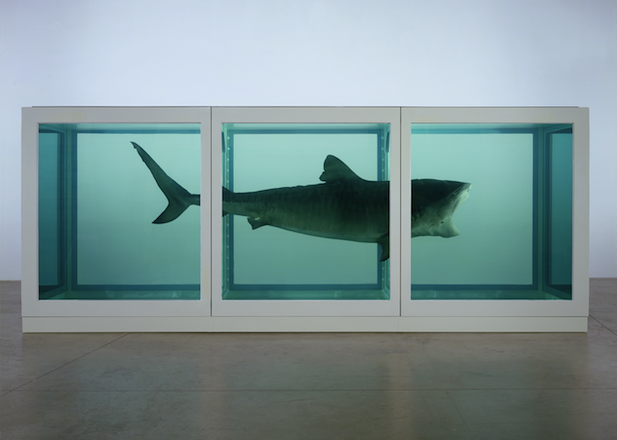

After a considerable hiatus in media-friendly British art, Hirst began making simple, bright work in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It looked good and was easy to reproduce (little of the detail was lost in its photographic reproduction). He spoke about death, a common topic for artists, writers and musicians throughout history. However there was something unusual in his “death” aesthetic: it was Spielberg meets Pop, more BOOM! than doom. It was bought up by one of cleverest of advertisers, Charles Saatchi, at a time when the public was becoming more fluent in the visual language of advertising than art. Hirst’s neo-pop aesthetics and wonder-child reputation were news-friendly and perfect material for the Saatchi spin. Hirst was producing recognizable images, with the (conveniently inconceivable) subtext of mortality. Never mind that there is no lurking turmoil here, no dark quagmire or final raspy wisps. Hirst’s death is no confrontation of life, not real life anyway, not the one I suffer from. It’s the kind of death that might affect, say, a man in a toothpaste ad. The shark, the spots, the pill-filled vitrines: they are all commodifications of a kind of ad-death and serve as a background for this extraordinary campaign with the liminal typeface, H-I-R-S-T.

As if following the advice of another great business strategist, former CEO of General Electric Jack Welch, Hirst decided to “choose a general direction, and then implement like hell.” His works have become icons, continually fabricated and reappearing, decade after decade, spots after sharks, sharks after spots. In his campaign, the product isn’t physically different from the branding. The work is the campaign, and the campaign the work. And the Hirst campaign has yet to perish outside ad-world, continually feeding the brand out to anyone who’ll take, play or publish it, while watching huge, corresponding hikes in art market value.

Despite the strapline of death, this dynamic shows no signs of dying. Here we go, trickling along to Tate in our droves to see it all rot and buzz in three dimensions, the things behind the images, and feel the obligation to wonder why—despite Hirst’s great fame—the work doesn’t provoke any kind of physical or mental response. The answer is that it doesn’t need to. Good branding has never improved quality; its game is to breed familiarity. Outside the exhibition, on the poster-boards of the cities and the wallpaper of our newspapers and magazines, the campaign’s slick, shiny surfaces trend on loop. As long as the buzz keeps going, he is the genius, and we, I, the fool.

Courtesy of Damien Hirst and Science Ltd.

GOODBYE TO ALL THAT by Laura McLean-Ferris

It was, as it turns out, the right time for a historical survey show. When it happened, something was ending, or perhaps it had already ended. The embers of cigarettes were dimming in the ashtrays. “Contemporary art has become historical,” wrote Liam Gillick in 2010, “a subject for academic work.” He locates the era of contemporary art as a period that began in 1973 and ended in 2008, with the financial crisis kicked off by the collapse of Lehman Brothers, an event that in the art world will always be associated with Damien Hirst’s multi-million pound auction of his own work at Sotheby’s.

There are two uses for the word “contemporary.” One stands for the traditional sense of being “in time”; the other describes a stylistic and economic epoch as it relates to art. And there is, perhaps, no artist more “contemporary” than Damien Hirst. In terms of coalescing with his time, he is emblematic, the epitome of an economic cycle in which the rich became very rich, and the poor became even poorer. Hirst’s work is there through it all, with early scruffiness, shocks and in-yer-face sensationalism, yuppies, New Labour, art fairs, bling and then the crash. It’s doubtful that he will be the artist to illustrate anything beyond that, but there’s a looping circularity to this period that is reflected in his art. Works such as A Thousand Years (1990), a bleak image of the ever-generating short life cycles of flies, or The Acquired Inability to Escape (1991), a depressing airless vitrine housing a generic, cubicle space for white collar office worker, retain effectiveness and relevance to the trappings of certain living conditions which have come full circle today.

But Hirst also attracted thousands of collectors and viewers to the thing that came to be known as contemporary art. People were transformed by a need to have it in their lives. Hirst’s vitrine works, pharmacy works and spot paintings looked like contemporary art in a way that nearly nothing else did, particularly in Britain, and his retrospective exhibition at Tate Modern throws into relief how Tate Modern’s own own brand of playful acid colors on clean white backgrounds resembles the his aesthetic. “This is so contemporary,” is what they say. The work anticipated the look of iPhones and Ikea. “The people visiting our ruins see nothing but a style,” wrote Jean Cocteau, and the style that people visiting our ruins will see has been marked indelibly by Damien Hirst.

Hirst continued to push the luxuriant end of his work that dealt with death: diamonds and gold rather than fags and office chairs; the intestines of angelic statues rather than plastic medical models; the short lives of gaudy butterflies rather than flies. As a writer who chronicled the end of the sixties and saw it turn into a long hangover of the seventies Joan Didion wrote “Goodbye to All That” that it “is easy to see the beginnings of things, and harder to see the ends.” In this case, I’m not so sure it was difficult to see the end. It’s an end that is stuck on a loop, exemplified by those bright, attractive butterflies in white rooms that live, procreate and die whilst beating out the words “contemporary, contemporary, contemporary” with their wings.

Courtesy of Damien Hirst and Science Ltd.

THOUGHTS ON DAMIEN HIRST by Carson Chan

Not long ago, I told gallerist Gavin Brown that when I saw my first Damien Hirst dot painting, the thoughts going through my mind had nothing to do with form, color, composition or concep—standard items of inquiry for many art viewers—but rather provenance, market value and point of sale (Kaleidoscope, Issue 14). At what point does art stop being art and become fiat currency, I asked Brown. What is the price threshold in which artwork trades its value: aesthetic for monetary? What level of artistry can speak above the blaring pronouncements of an object worth 50 million pounds? For Brown, Hirst’s artwork is “the perfect vessel” for communicating these questions—prescient as they are. I would accept this conceit if Hirst had convinced us that that was what he had intended. In any case, if it were art about its market, the writers of his new Tate Modern exhibition have tried to obscure it, elaborating instead on the theme of mortality that he presents with uninhibited blatancy (dissected animals preserved in formaldehyde, medicine cabinets, anatomy models, cigarette butts, and so on). Art objects that cost a lot of money and, as such, make us think about our relationship with money, are not the same as art objects made expressly to question money. It serves us better to see Hirst as a business than an artist, in which case we might learn more from him. It is easier to argue that he makes art objects to make money than to convey ideas.

Of course, contemporary art production cannot be separated from the markets in which they serve. The fact that art produced according to the logic of the market doesn’t negate its artistic significance. Artists, like everyone else in a market society, must make a living, yet art has no intrinsic monetary value (save for material). The very human ability to appreciate art requires no monetary exchange. Like all things, the monetary value we assign to art is the result of a strange calculus of both reason and its opposite. Prices are derived from a commodity’s supply, its projected demand and then considered with all the sundry and illogical hopes, desires and velleities that drive us to buy. Monetary value has always been a confabulation of real and imagined needs. When the real needs (capital investment) overtake the imagined ones (artistic veneration), when a commodity is traded purely as a currency, does it still make sense to discuss it otherwise? Recall the 17th century Dutch Tulip mania or the many accounts of slave trade in human history. Neither tulip (which retailed for more than ten times the yearly wage of a craftsman per bulb) nor human life factored much in the cold math of commerce; both were traded purely for their economic gain. Hirst’s work, the majority of which retails for about a million pounds, caters to a particular sector of society that needs to unburden themselves of large sums. (40% of the buyers of his 2008 Sotheby’s auction were first-time art buyers from Russia and the Middle East.)

I would nuance Gavin Brown’s claim. Hirst’s work is not the perfect vessel to convey the ideas of market culture: it is market culture. It doesn’t represent something: it is that thing. When we look at Hirst’s work, we are not looking at art about the market, we are looking into the shiny, irresistible visage of the market and the bankruptcy of a system that has cast itself from the subtle and sublime qualities of being human.

This article was published on the occasion of Damien Hirst’s retrospective at Tate Modern on view until September 9th.