ARCHIVE

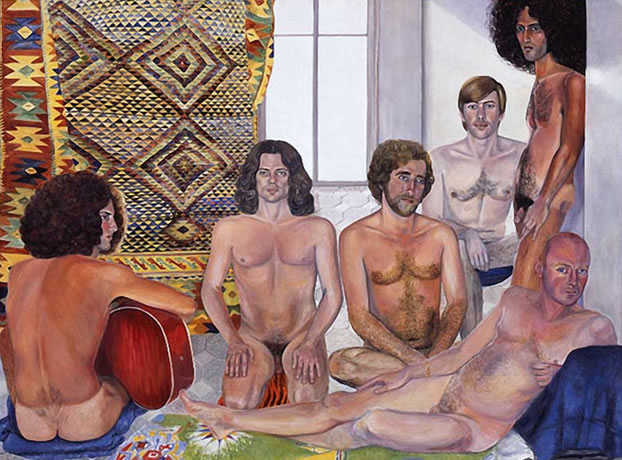

SYLVIA SLEIGH

words by Joanna Fiduccia

Courtesy of the Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago

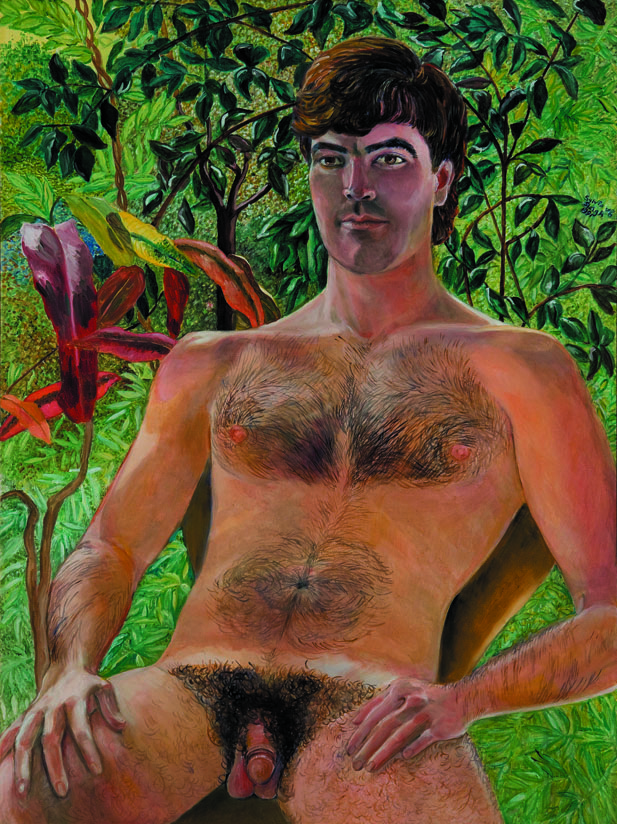

Sylvia Sleigh was 57 years old when she met Paul Rosano. In those days, numerous New York artists and critics came under the British painter’s brush, but it was Rosano she seemed to love the best. He was her Victorine Meurent, dark and lithe and very young. Not much is known about him, save that he modeled at the School of Visual Arts, in New York; that he played the lute; and that he bore an uncanny resemblance to Jane Morris, Gabrielle Rossetti’s favorite model, sharing her closeset eyes, symmetrical features and luxuriant mane that rises in a dark corona around a tapered face.

Rosano appeared repeatedly, and sometimes multiply, in Sleigh’s paintings: twice in her most famous work, The Turkish Bath (1976), and twice in Paul Rosano: Double Portrait (1974). In the latter, he stands in front of a mirror so that we see both sides of him: his torso, wreathed with hair like iron filaments disposed by erogenous magnets; and his back in shadow, a blue-beige tan line boosting Sleigh’s attentive contouring of his hindquarters. Sleigh’s model is two-thirds the Three Graces, a single beauty seized, god bless, from every angle.

In 1975, the curator Judith Van Buren included this double portrait in her exhibition entitled “The Year of the Woman,” at the Bronx Museum, which at the time was located in the district courthouse. Justice Owen McGivern launched a complaint. Said the Justice: “We are all in sympathy with the arts, but explicit male nudity in the corridor of a public courthouse is something else.” Van Buren successfully defended Sleigh’s work on the basis of its classical pedigree, and yet the Justice’s “we”—equally the illusion of a universal audience and allusion to a vox judicialis—expresses more about Sleigh’s radicalism than her more art-savvy proponents have to date.

Courtesy of the Estate of Sylvia Sleigh & Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich

Sleigh, her advocates assert, painted men as objects of desire without, however, thereby objectifying them. “I don’t mind the desire part,” Sleigh has often explained, “it’s the object that’s not really nice. I opted to paint men in the way that I appreciate them, as dignified and intelligent people.” Thus her nudes—both the women she painted throughout her career, and the men that established her, however perfunctorily, as a feminist artist—were also portraits. It’s hard to dispute this (Sleigh’s realism tenderly renders details with an “almost awesome intimacy,” in the words of critic Michael Benedict), and yet her characterization has come at the expense of the eroticism clearly issuing from Sleigh’s work. After all, it was not sympathy with Rosano that McGivern was lacking, but rather with the art itself, which is to say, with Sleigh’s ardent gaze.

The painter was born in Wales in 1916 and educated at the Brighton School of Art. In the 1950s, Sleigh began an affair with the critic Lawrence Alloway. Together, they immigrated to New York, where Alloway had begun a curatorship at the Guggenheim Museum. The subjects of Sleigh’s portraits in those years— Betty Parsons, Eleanor Antin, Arne Glimcher, among many others—testify to the couple’s embrace by the local art scene. In 1968, Sleigh, already grouped with the likes of realist painters Philip Pearlstein and Alfred Leslie, painted the first of many nudes that would cement her reputation as one of America’s least-offensive feminist artists. Nude Portrait of Allan Robinson offers the aforementioned figure gazing impassively at the viewer, his body pale as the shearling beneath him. Anything scandalous about the painting has since mellowed. Today, Robinson’s nudity is as understated as Sleigh’s palette; improbably tranquil, his body betrays none of the tensions expected from inverted gender roles. The fantasy here is less erotic than jejune, as though the struggle for gender equality could be ended simply by stripping down and swapping spots. Sleigh’s politics appeared similarly abstract. Although she participated in almost every large-scale American exhibition of feminist art during her lifetime, and showed with the women-run A.I.R. Gallery and SoHo 20, which she co-founded in the early 1970s, Sleigh abstained from direct actions like Fight Censorship, a feminist collective that addressed institutional bias, such as that which jeopardized her Double Portrait in 1975.

Courtesy of the Estate of Sylvia Sleigh & Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich

If the Robinson nude was a demure opening gesture, by 1971 Sleigh was bold enough to produce Philip Golub Reclining, a Rokeby Venus for twentieth-century gender politics. Golub, the teenage son of Leon and Nancy Spero, lounges with his back to the viewer, gazing into a mirror that reflects not only his face, but Sleigh at her easel, recalling another Velázquez reference in the intricate lattice of sovereignty, power and vision of Las Meninas. The unconventional relation—a woman (Sleigh) viewing a naked man-boy (Golub)—is splintered by the mirror, in which both figures gaze simultaneously at the viewer and at a highly androgynous nude. It hardly seems arbitrary that Sleigh structured two erotic paintings around a mirror. Substitution of male models in roles previously held by women results in doubling of one kind or another: either in farce, as demonstrated by Linda Nochlin’s photograph Achetez Des Bananes (1972), in which a fleecy male model in tube socks and little else holds a tray of bananas in a parody of a nineteenth-century advertisement for apples, or in the rehearsal of homoerotic art. The former ends only in titters, while the latter reinforces the exclusivity of male eroticism; neither are very useful for a feminist agenda. Sleigh’s brilliant stroke was to play out erotic imagery in the looking glass, redoubling this doubling and driving some conceptual running-room between viewers and centuries of conventions around the gaze and the nude. Unlike the painting-as-window, which provides an invulnerable vantage to survey the nude, the painted mirror renders the viewer conspicuously invisible. It is this position, then, bundled up in a powerful art-historical pedigree that includes Velázquez and Édouard Manet, that begins to look like a response to Justice McGivern’s complaint. The viewer of Sleigh’s paintings stands precisely in something like the “corridors of the law,” in the channels of power, yet remains invisible to or outside the space of both decree and articulation.

Courtesy of Ursula Hauser Collection, Switzerland

Sleigh has more in common with Manet than just mirrors. A master of art-historical citations, his works salmagundis of Western painting, Manet created what Michael Fried described as Baudelarian “memory painting,” in which the past is made available through its echoes in the present, while the latter is buttressed by the former. As memory painting, Sleigh’s Turkish Bath does not initiate a new aesthetic genre—i.e. the brothel, but with men!—but rather layers traditions to reveal a female, heterosexual erotic gaze, potentially there all along. The Turkish Bath, whose composition recalls the eponymous painting by Ingres as well as Titian’s Venus and Lute Player, among others, features four New York critics—Alloway, John Perreault, Scott Burton, and Carter Radcliff—flanked by two Rosanos. This complicates the “sympathetic” portraiture other critics have read into Sleigh’s rendition of the bath, which is full of variety and expressivity in contrast to Ingres’ dough-heap of flesh. Her favored model’s double apparition is a miraculous improbability in a realist painting, something Sleigh’s citations might distract her viewer from noticing. Using Rosano, Sleigh draws an erotic perimeter around the critics, emissaries of the word. She carves a passage for the feminine erotic at the congested crossroads of the nude and the portrait, a place where she can revel in an inconspicuous fantasy.