ARCHIVE

FRANK BENSON

words by Alessandro Rabottini

Courtesy of the Artist; Sadie Coles HQ, London; Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York; and Overduin and Kite, Los Angeles

Long before the critical terminology of contemporary art began to misuse the concept of the “end”— the end of modernity, the end of the organic body, the end of reality—the language of art discussed representation as a space rife with enigmas and formal substitutions, a domain of visual perfection that had little to do with things human and organic.

Before we became convinced in recent decades that the “post” condition—postmodern, post-human, post-historical—was permanent and irreversible, visual art had already gained centuries of experience in surmounting nature and sublimating and replacing reality and history. From classical sculpture to pop art, through the baroque, Surrealism and neo-geo, art has attempted to defeat nature and reality, especially when they seemed to be amplified by their likenesses. The greater the verisimilitude, the more nature ended up collapsing into its opposite, crushed by the weight of an unlikely and unnatural hyper-realism.

The sculptural and photographic work of Frank Benson—born in 1976, he lives and works in New York—dialogues with this ever-present resource of art: the idea that representation and figuration are the places of maximum abstraction and radical artifice. While Benson’s photographic works have a clarity that gives the images a nearly tactile quality, his sculptural works travel along the same trajectory in the opposite direction, so that they seem to be beamed in from the domain of images, occupying an ambiguous space between objects and surface, maximum definition and maximum density.

This dialectic between the space of the photographic image, be it analogue or digital, and the space of sculpture has recently become an extremely productive field of interest for artists from Benson’s generation. Albeit with different approaches, in recent years artists such as Elad Lassry, Giuseppe Gabellone, Seth Price, Trisha Donnelly and Roe Ethridge—to name only a few—have produced works in which two-and three-dimensionality seem to merge; surfaces, depths, visual patterns and volumes appear to exist in state of osmotic flux, as if there were a constant process of digital morphing among objects, images and materials. Filming techniques that permit ever-greater definition of images and sophisticated postproduction software have not only made us more familiar with the processes used to tweak images, but they also allow for the extension of these very processes into production of spaces and objects. Editing a picture with photoshop is now akin to constructing, shaping and assembling, whereas certain properties of the digital image—flexibility, mobility, the speed with which it can be transmitted and adapted to different formats and media—have now been extended to the processes that build the real and analogue world.

Courtesy of the Artist; Sadie Coles HQ, London; Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York; and Overduin and Kite, Los Angeles

Today it seems that the fully-integrated nature of image-making devices—on which one can not only create an image, but also edit, manipulate, and transmit it—is destined to influence a mature, mannerist stage of artistic object production, which will redefine the parameters of the objects we still perhaps too simplistically refer to as “sculptures.” See, for example, Human Statue (Jessie) (2011), which is Benson’s most ambitious work to date, and the most profound synthesis of his visual and conceptual universe. This female figure made of bronze and noir belge (black belgian marble) has the presence of a Greco-Roman sculpture, but its visual relationship with classicism is not purely based on the simple quotation (or the mimicking) of classical elements. Each part is also not simply “contemporary,” but is forever tied to a particular fashion popular when the statue was made: the hairstyle, the sunglasses that conceal almost half of the woman’s face and the cut of the dress represent the “circa 2010/11” re-issuing of the forms that defined the fashion of the 1980s— and in a matter of months they will be obsolete.

The outcome of stylistic revival, these elements define a period in which we had a hard time finding an “original” look. Soon they will remind us of just how weak these years were in terms of iconic invention. Accordingly, Human Statue (Jessie) is so closely tied to a particular, popular moment of recent style that it appears to be a fashion photograph transferred to the noble materials of sculpture, an internal contradiction that pits the fleeting nature of stylistic trends against the obdurateness of marble and bronze. A similar absolute adherence to present time, style and form can be found in works such as Fall ’91 (1992) by charles Ray, and some of the images from the Made in Heaven series that Jeff Koons made with cicciolina in 1989. In both we find the perception of time present so exaggerated and flaunted that it almost becomes a form of abstraction, a quality that Human Statue (Jessie) shares.

The hairstyle, the heavy makeup and the suit worn by Ray’s oversized woman are so rooted in the late 1980s and early ’90s that they now create the immediate and inevitable effect of “a blast from the past.” Furthermore, the sculpture’s faithful material likeness to a commercial mannequin is powerful, as it goes against the parameters of traditional sculptural language and presents what might seem to be a contradiction in terms: a readymade with altered dimensions.

Courtesy of the Artist; Sadie Coles HQ, London; Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York; and Overduin and Kite, Los Angeles

Fall ’91 calls into question the concept of sculpture at the moment in which it creates a dialogue between the processes of industrial production initiated by minimalism and a radical form of expressive apathy that inevitably echo American pop art. Koons’s baby face in Made in Heaven is another index of unrepeatable and unyielding temporality we rarely find in self-portraiture. His smiling face is among the most iconic and media-ready of the contemporary art world. Seeing such a young Koons in the pornographic poses of Made in Heaven not only gives us an absolute perception of the time in which these images were made, but it also recreates the perfect overlap and contraction of style, history, styling and time.

The works of charles Ray and Jeff Koons are relevant to a discussion of Benson’s work not simply in their neutral delineation of present time, but also in terms of the relationships that they propose between sculpture and production processes. In the case of Benson’s Human Statue (Jessie), the reference to fashion photography is direct, as the initial phase of the production of the sculpture, which determined the figure’s pose and styling, was a photo shoot of a model, whose features were only later captured through a 3-d digital photo scan. The bronze and marble parts of the statue were then made based on this high-tech optical mapping, which is able to capture the tiniest details, some of which—the veins of the twisted feet and the blemishes on the model’s face—were even exaggerated by the artist.

There is an excess of verisimilitude in Human Statue (Jessie) that makes it alien: it is a rendering that does not pertain to the instability of reality but instead embodies the idealized, transcendent realm of the hyper-real. The importance of production processes in the actual conception of this work once again brings us to the aesthetic and conceptual value that artists such as Ray and Koons proposed in their idea of creating sculptures that acted as sublimations of certain mechanical production processes. Above all, we can examine the way both have brought banal, everyday objects into the dazzling realm of formal perfection that characterized the 1960s-era work of Los Angeles–based Finish Fetish artists like John Mccracken, Larry Bell and Ken Price, who exercised absolute control over materials and industrial processes.

Courtesy of the Artist; Sadie Coles HQ, London; Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York; and Overduin and Kite, Los Angeles

I’m not sure, however, that Jessie merely suggests the idea of a body that has overcome the human. Consider how greatly indebted Benson’s work’s aesthetics are to the pictures of Helmut Newton and Robert Mapplethorpe: in both of their oeuvres, the body is portrayed in a state of tension and extreme self-control, poised between allusions to classical postures and body-building, hyper-theatricalized makeup and S&m constrictions. While there is no trace of spontaneity or free movement, if the imperative here seems to be that of making the body resemble a statue and the face a mask, at the same time the rigidity of those bodies and poses and the extreme definition of facial features convey a sense of pride and conscious display, of confidence and self-determination. Likewise, in many of the photographs in which constructivism and Surrealism converge— consider Man Ray, Herbert Bayer or László Moholynagy—the body is multiplied, bound, sectioned, assembled and amplified, but it is never unobtrusive. Its non-integrity never demeans it. Rather, there is a sense that this manipulation and control is ultimately an act of profound freedom and liberation, be it from desire, the unconscious or individuality.

Many of Benson’s works, photographic and sculptural alike, present images that are sectioned and incomplete; they evoke a suspension of motion or gravity, seemingly negating the laws of physics, despite the fact that the objects and images show powerful solidity. In short, many of Benson’s works seem to contemplate the idea of extreme control.

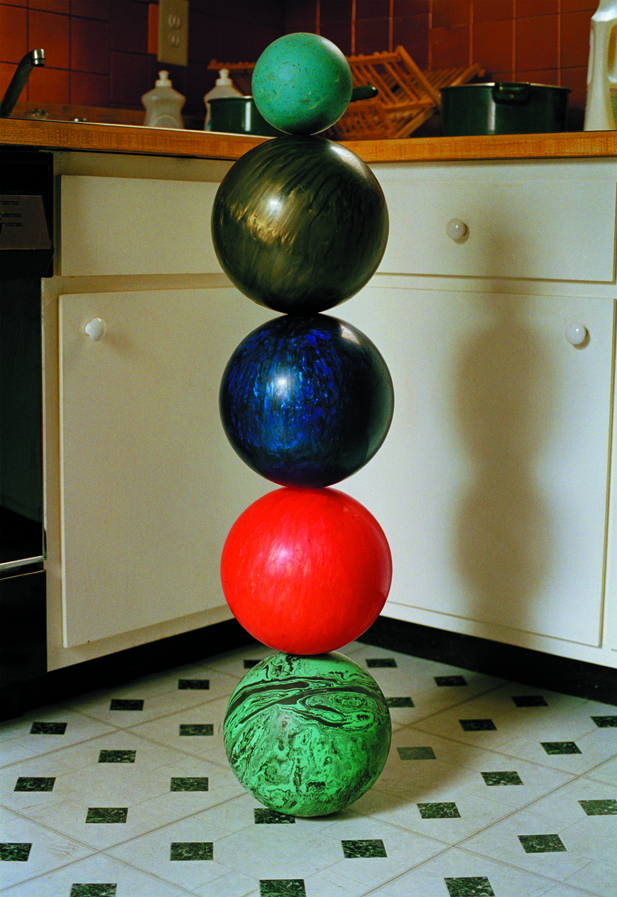

For example, Bowling Balls (1998) shows the impossible equilibrium of five stacked bowling balls, while Foam (2003–7) depicts an excrescence of spray polyurethane foam that resembles a geological formation. In the 2008 work Untitled (Changer), meanwhile, we see what resembles part of a projector or computer, but what in reality is the tray from a cd changer that has been melted slightly to create protrusions in the surface, a mysterious object that appears as if it could be either an archeological discovery and an alien technology. despite the fact that these three works are photographs, all of them share an area of ambiguity between object and image. What we see looks like the documentation of a process comparable to gestures (the balancing of weights), materials (polyurethane foam) and procedures (casting) that pertain to the language of sculpture rather than photographic composition. The more these images highlight suspended motion, the more they reveal density, depth, solidity and endurance.

This relationship linking immobility, the absence of temporality and formal perfection also returns in Benson’s sculptures, in which exhaustive planning is at least as central as the actual execution, leaving no room for even the slightest imperfection. All of Benson’s work is centered on the almost total absence of improvisation, in both the materials he chooses and the procedures he employs. Materials requiring mechanical workmanship and finishes that barely register the traces of the passage of time—polished steel, acrylic and powder paint, urethane, aluminum—become part of a slow process of elaboration accompanied by non-expressive technologies such as casts and 3-d scans, eliminating any remaining trace of what might be called a sculptural “gesture.”

Courtesy of the Artist; Sadie Coles HQ, London; Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York; and Overduin and Kite, Los Angeles

Chocolate Fountain #2 (2008) is a sculpture that is chiefly composed of a perceptual paradox: mirror-polished stainless steel reflects the fauxmelted chocolate, as it appears to flow smoothly from one level of the fountain to the next. Capturing what appears to be the viscous movement of liquefied chocolate, at once hypnotic and almost imperceptible, the gleaming steel of Benson’s work forges a relationship with the milieu of sculpture that, from Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne to Koons’s Celebration series and Robert Gober’s hyper-realistic compositions, has imbued the most stable materials with an almost indefinable perception of temporality, a feeling of the unexpected and the ephemeral.

Can we describe the moment in which Bernini’s nymph is turned into a plant as a pre-digital form of morphing carved in marble, as if the concepts of metamorphosis and movement could paradoxically be formalized in materials that are unaffected by the passage of time? many of Benson’s works seem to revolve around this perceptual aporia. Consider, for instance, how many of his works involve figures that allude to flora and fauna or, in any case, the realm of the organic and perishable. Turtle (2009), for example, contemplates the image of a sea turtle that sprouts hands in lieu of limbs and a head. The forms of Untitled M1 and Untitled M2 (both 2010) evoke those of quirkily cut watermelons, while Swan Gourd (2005) presents another form of cutting and omission on the neck of gourd that resembles an unnaturally colored swan. Portrait of the Artist’s Mother (2004), in turn, employs the image of a pear with an odd excrescence in the middle of an assemblage of incongruous figurative elements.

Many of these surrealistic compositions emphasize the idea of isolation and suspension—be it of time, motion or life—through the use of display devices. For example, Turtle as well as Untitled M1 and M2 are suspended, one from the ground and the other from the wall, through the use of mechanical arms of the kind used to hold televisions or other technological devices, as if to underscore the gap between two different forms of temporality and decay, the natural and the artificial, that end up converging in the final unity of these works. While Benson’s visual universe seems to have defeated time through the hardness and durability of his materials and the production techniques he uses, at the same time his images appear to woo an idea of abstraction that manages to draw their final conclusions from time, cliché and reality.