ARCHIVE

DIANNA MOLZAN

Essay by Jonathan Griffin

Every painting — every good painting, at least — is a problem. This problem can come in all shapes and sizes: a problem with the world, a problem with painting, a problem with one’s self. Whether it’s the curious vibrational effect of two colors in proximity to one another or the crisis of consumer capitalism, a painting embodies or responds to the impetus for its own creation. Not all paintings solve their problems; most don’t even come close. Many create more problems. That’s okay.

For Dianna Molzan, the primary problem that her paintings address is largely self-imposed. In simple terms, it could be boiled down to the following question: Why does a painting, an object made of wood and textile and metal fixtures, conventionally ignore the materials of its own construction? This is a good problem because it engenders a slew of further problems. Such as: Why do we habitually disregard frames and mounts and borders when considering a painted picture? Does a painting contain, within its constituent parts, a hierarchy of value? Where does the painting end? Where does its value end?

The originary problem of Molzan’s paintings is, arguably, only a conceit. In the present day, painters are no longer confined to the traditional media of oil paint and canvas. Perhaps they never were. Some of the most important paintings in the historical Western canon are frescoes on plaster, or painted directly on wood. In the twentieth century, artists used all manner of industrial and domestic materials to make paintings, and in contemporary discourse there is virtually nothing that could not make a case for calling itself a painting. (A 2011–12 series by Urs Fischer, coincidentally titled “Problem Paintings,” were predominantly silkscreen on aluminium.) Furthermore, it could be argued that most of Molzan’s works are not really paintings at all, but simply sculptures made of wood and canvas and paint.

As a fledgling artist, Molzan continued to engage the multiplicity of options available to her. Yet even as she made videos and sculptures and explored performance, painting remained her touchstone. Not a natural multitasker, she quickly realized that she lacked focus, so she placed restrictions on herself. From then on, her work would only be made from the elemental components of traditional painting: paint (almost always oil), textile (mostly canvas but also linen and, more recently, silk) and wood (fir and poplar). Paint would be applied by brush. She restricted her paint purchases to primary colors, plus white, from which she mixed all other colors (although the hard-to-mix shades of magenta and turquoise have sometimes required her to bend her own rules).

All artwork images courtesy of Overduin and Kite, Los Angeles.

Photography by Brian Forrest

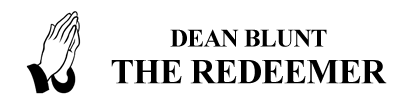

By confining her activities to these limitations, Molzan has, paradoxically, accessed a deep and wide territory of potential in the very center of the painting tradition. She has not approached her problem from its margins, nor attempted to broaden its scope with novelty or esoterica. Simultaneously, her critique is mainstream and of the mainstream. Molzan has, in her words, “gone in through the front door.” Take, for example, the works she has made by unravelling and removing the threads of the canvas itself. Having fixed a canvas over a wooden stretcher, Molzan cut into the fabric and teased out all the vertical strands, leaving only the horizontal threads still fixed to the sides, causing them to hang slackly in downward arcs.

The first time she did this, in 2009, Molzan said it was “like finding something hiding in plain sight.” The most obvious and yet overlooked property of the painting was suddenly exposed and shown to be a uniquely unstable ground for further painterly activity. Likewise, in an untitled painting from 2010 (Molzan declines to title any of her works), the artist spattered a light drizzle of red, yellow and blue paint onto the white primed threads. As such, color itself, like the surface it rests on, is separated into its primary forms. The effect, however, is far from reductive. Untitled (2010) is a humble miracle, a plainspoken revelation that transforms simple pictorial ingredients into an unexpectedly sensuous sculptural experience.

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, recently mounted the exhibition “Destroy the Picture: Painting the Void, 1949–62,” the last curatorial effort by Paul Schimmel before he departed the institution. The exhibition took as its focus the first twentieth-century paintings to have their canvases punctured by their makers in order to reveal the emptiness beneath. For artists such as Alberto Burri, Lucio Fontana and Shozo Shimamoto, all haunted by the terrible memory of World War II, such pictorial injuries were representative of the nihilism that they felt had come to haunt illusionistic representation. The painted canvas was, too, an analogue for the human body: paint became exposed flesh, canvas a skin and the stretcher a skeleton.

Though she toils in the wake of these artists, Molzan shares little of their postwar angst. She has described herself as an enthusiast, with an additive practice that is concerned with adornment and decoration as much as it is with deconstruction. In contradistinction with the art of “Destroy the Picture,” the canvases in Molzan’s paintings are in dialogue not with human skin (a rather melodramatic and now clichéd analogy, one might argue) but with textiles and design, from mass-produced patterns to popular color schemes. Accordingly, the work loses its potential terror; the stakes are lower, but also closer to home and more believable. The hanging threads of Untitled (2010) evoke the bagginess of a loose sleeve or a complex necklace. A work from 2011 is almost all void and no painting: an empty rectangular stretcher that is sleeved in ruched, offwhite canvas. The effect is to temper the structure’s unapologetic starkness with soft folds that bring to mind the kind of “scrunchie” hairbands popular with girls in the 1980s.

All artwork images courtesy of Overduin and Kite, Los Angeles.

Photography by Brian Forrest

And as soon as fashion enters the conversation, so must history. Nothing remains contemporary for long; stylistic tropes, in clothes just as in paintings, have their day and are discarded or resurrected. Molzan is especially skilled in summoning a hard-to-define datedness in certain color palettes, patterns and paint applications. The flamingo pink, mauve, peach and sage that she deploys on five vertical bars of stretched canvas in a work from 2011, for example, evoke a blouse from the 1920s, or curtains from the 1940s, or even plastic laminate from 1980s era furniture. The work is disarmingly familiar but also out of reach. We recognize it but cannot quite place it.

The same is true of what might be the gaudiest work in Molzan’s oeuvre, from 2012. As with a number of her paintings, this work stands slightly proud of the wall thanks to square feet fixed to each of its corners. Its all-over pattern boasts involved polygons of red, blue, purple, brown and jade green, and only on sustained inspection turns out not to be a pattern at all. If we were to try and locate the bizarre, irregular composition within an aesthetic context, it would probably be to cheap curtain design or bus upholstery — rather than modernist painting — that we would turn.

It goes without saying that “fine” art and quotidian design have long had a symbiotic relationship. Styles and patterns have been passed, especially in the postindustrial West, back and forth between the different applications of form and function, between common and refined systems of value. The most self-consciously frenzied moment for this traffic was in the 1980s, when designers such as the Memphis Group, Frank Gehry and Vivienne Westwood incorporated cheap or industrial materials into their costly and highly desirable products. It should perhaps be no surprise that this is a period to which Molzan returns often in her work — and employs it, Tardis-like, to access other moments in 19thand 20th-century visual culture. The flecked surfaces of Ettore Sottsass’s laminate furniture for Memphis are revisited in paintings such as Molzan’s 2010 work in which three folds of canvas lap around a bare wooden stretcher, forming a tricolore ice-cream-like relief. Her dazzling paint effects are also reminiscent of the experimental ceramic glazes of fellow Californian Ken Price, an artist whose early work must surely have been an influence on Sottsass, and who wilfully ignored the classical hierarchies between utilitarian crafts and fine art.

All artwork images courtesy of Overduin and Kite, Los Angeles.

Photography by Brian Forrest

A paint spatter, notes Molzan, can never be just a paint spatter. Depending on its density and size, it can be a Jackson Pollock spatter or a kitchen countertop from the 1960s. It can be a spatter emblazoned across a sweatshirt sold by Westwood and Malcolm McLaren at their late-1970s-era London store Seditionaries, or it could be the popular, aestheticized version seen on mass-produced denim and t-shirts in the 1980s. Or, just maybe, it could be the dripped paint effect applied to $525 Maison Martin Margiela sneakers in the designer’s Pre-Fall 2012 collection.

Despite the apparent casualness with which Molzan often applies paint — as if her objective is to simply fill up a surface with color or pattern — there is no possibility of such effects remaining neutral. Her concerns may seem predominantly formal but the language of fashion and design is freighted with narrative. The artist remembers owning a pair of paint-spattered trousers while growing up in the rural Pacific Northwest in the 1980s, and feeling unbelievably urban and sophisticated in them. Recently, I myself have seen jeans sold in Gap that have daubs of white paint ready-applied, as if the owner had just finished painting a newly acquired home (signified as being wealthy enough to buy a house but not wealthy enough to hire a professional decorator). The demographic associations of such design tropes are staggeringly precise.

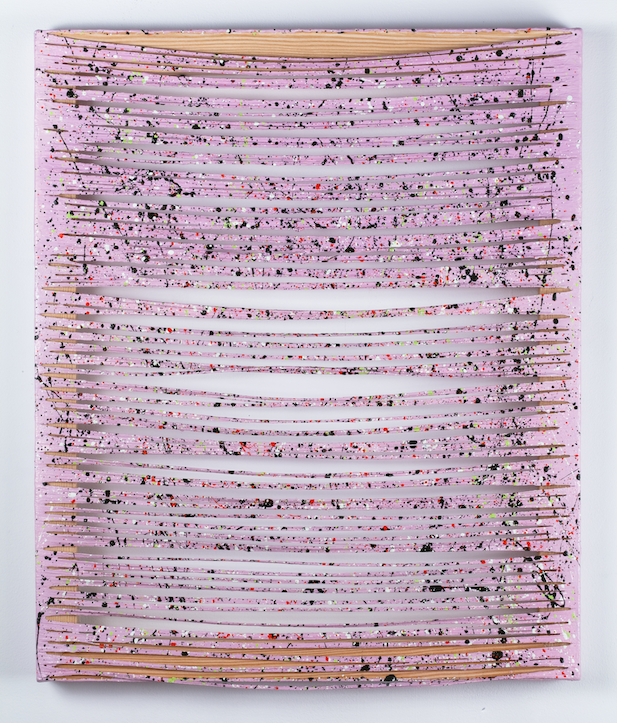

To that end, this is how class identification and personal aspiration find their way into Molzan’s work. Hers is a practice of precision, refinement, taste and connoisseurship. Despite her work’s orientation around both high and low cultural coordinates, it always makes an argument for its own value. It does this partly through the delicacy of Molzan’s constructions: carefully sewn ropes encase hundreds of separated canvas threads, or evenly knotted nets pull tight across wooden stretchers. Even when Molzan makes marks that are intended to look careless, such as her “palette cleaner” paintings, in which crusts of colored paint accrue as she (supposedly) cleans excess paint from her brush, she aims to make the very best version of that careless-looking painting that she can. Bruce Hainley has called it “italicized brushwork.” Molzan herself has described the process as “painting in drag.” Her version of drag is never, however, ironic or camp. Instead it hews close to the hopeful notes of transformation and self-identification that that word also implies.

All artwork images courtesy of Overduin and Kite, Los Angeles.

Photography by Brian Forrest

Molzan’s paintings also make their claim to value simply through their likeability. They are, for want of a better word, pretty. That is not meant in a dismissive or derisive way; prettiness is but one weapon in their expansive armory. Molzan’s paintings have the ability to hook the attention of a viewer from across the room. Her palette is equally unthreatening — she typically prefers pastel shades that might, unthinkingly, be termed “feminine” — and the modest scale of her paintings rewards intimate engagement. Thus dense areas of painterly activity demand close inspection, as with a work from 2012 in which two narrow vertical canvases (inflected with a motley color scheme) are bound together by a sagging white net. And nets of thread appear in other works too, along with ribbons of canvas that connect discrete paintings — normally vertical bands of canvas stretched over wood. These devices are actual and metaphorical traps for our attention: it is as if our roving gaze was a wild animal that Molzan was aiming, sweetly, to ensnare. A work from 2012, in which the net is pinned to all four sides of the stretcher, seems to have caught not only our eye but also clotted masses of vivid color. Molzan is directing our attention not so much to this gorgeous central portion of the painting, but to the clean white wall immediately behind it. The same is true of all these net pieces. It remains the wall, not the painting, that is the real subject of the work.

If I have characterised Molzan’s work as revelatory and exposing, such a reading can seem contradicted by the artist’s predilection for illusion and visual trickery. For instance, a number of paintings appear to hover about an inch away from the wall, pushed forward by the corners of a thickly painted rectangle that is slipping off the canvas. In a work from her 2012, a lime-green rectangle sticks to a ground not of canvas but silk organza. The heaviness of the paint is at discomfiting odds with the ethereality of the silk — and explains, perhaps, its apparent slide towards the ground. Such an illusion does, in fact, point to an ordinarily disguised quality of the paint: its viscosity when wet and toughness once dried. As it happens, the painted corners are structurally reinforced. “Art is a lie that makes us realize truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand,” Picasso famously said. But he went on: “The artist must know the manner whereby to convince others of the truthfulness of his lies.”

All artwork images courtesy of Overduin and Kite, Los Angeles.

Photography by Brian Forrest

These are not the only tricks that Molzan likes to play on her viewers. Strange physical effects also transpire when paint appears to drip downwards from the canvas onto exposed struts of wooden stretcher, or onto the hanging fabric ropes that drape across the front of some paintings. A work from 2011 seems to show a hanging rope — a mess of clashing hues — that has masked not one but two areas of the same canvas from different color schemes. The work is indexical of a kinetic flip-flopping, an analogy for Molzan’s either / or approach to painterly decisions.

To that end, there is very little historical painting that Molzan is opposed to. She has expressed, in the past, her inability to choose between the positions of different painters — Joan Mitchell, Richard Tuttle and Matisse were the examples she gave — all of whom influence her practice in diverse ways. If she stakes a position of critique, it is an attack on the possibility, in the 21st century, of a singular critical position. She reserves the right to contradict herself. For some viewers, one work from her exhibition “Grand Tourist” at the ICA Boston, in 2012, might not be recognizable as a Dianna Molzan painting at all. In it, an explosion of blue, white and red pompoms decorate a brown linen ground. The work derives from her reflection on how American patriotism in Boston is so wildly divergent from patriotism in, say, Texas. It is intended as an unstable proposition. It is also in especially discordant dialogue with another recent picture by Molzan of Twombly-esque flower blooms. Can one think of blue flowers on a red background without thinking of nationalism? If not, why not? Are all interpretations only options?

We have recently witnessed an American presidential election in which the signifying aesthetics — a red tie here, a blue tie there — are as interchangeable as many of the candidates’ political positions. It is tempting to read Molzan’s project as a commentary on the contemporary impotence of aesthetic dissent. There was a time in recent US history, the artist reminds us, when choices of color or design were high-stakes decisions. Lives have been lost over less. But that time is over. In her own art, Molzan does not cast judgment on the current situation one way or the other; it is not entirely good, she implies, but it is not entirely bad.