ARCHIVE

A CULTURAL ENCYCLOPEDIA

words by Nana Oforiatta-Ayim

Courtesy of the artist and gallery i8, Reykjavik

Growing up, I had a mythic imagination of England, a place of sliced white bread, of rolling glades and hillsides, girls in straw boater hats, the Beatles, marmalade, a hand-bag toting queen. Memories of Ghana were of weighted gold, of semiotically patterned cloths, of late night Highlife, the tops of rainforests glimpsed through the mist, Kontomire stew, our first president’s distinctive hairline. And yet, somehow this vision was more filled with holes. It could be that because the books I read, the television I watched, the history I was taught at school, gave me a more complete idea of Europe and America. For a long time, I put this disjuncture down to a kind of colonial trauma, a non-appreciation of our own gifts and offerings, but the older I got the more I realized it was to do with our stories.

The pride in the voices of schoolboys belting out Jerusalem in spired chapels, the myths of Albion and a United Kingdom, were all predicated on narratives of conquest and achievement, of empire and industrialization. These grand narratives were cemented by the popularization of the printing press, through periodicals and, most importantly, encyclopedias. The ideas that underlay them were exchanged and disseminated through study tours and cultural and scientific societies. The material manifestations of the ages of Discovery and Enlightenment were housed in glass cases in institutions specially built for that purpose, the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Science Museum. Successive stands—even those taken by punk or the Institute of Contemporary Arts—that initially stood counter to the dominant cultural narrative eventually became part of it.

Ghana, as a country only fifty-odd years old, inherited narratives of dominance from its states and kingdoms, like those of the Akan. The dynamic, elliptical forms of the Ayan and Apae, the various poetries of provenance, made sure that history was never frozen, never static. Akan sculptures of gold and terracotta, glass-cased and backlit in the British Museum in England, were in Ghana brought to life at the Odwira and Ohum, occasions that drew mass audiences absent from the comparatively deadening spaces of museums. The intellectual movements and innovations of figures like Joseph Casely-Hayfords, J.B. Danquahs, and Kwame Nkrumahs brought about the same far-reaching shifts in their country as did Locke, Hobbes and Hume in theirs, but did not find themselves the arbiters of an age—except perhaps of that known as ‘post’ colonial, an age defined by that which was outside itself.

For one narrative to be civilized, the other had to be dehumanized. Ghana and the new nations of Africa, still at the nascent stage of self-naming, took on these narratives of the shadows, the heart of darkness, the scar on the conscience of the world.

And yet, the nature of the stories we tell ourselves seems to be changing. For every story that we see on television or read about in a book, we find another, on the Internet, presented by a multiplicity of voices, ranging from Argentina, Iceland, Korea, Namibia. Their reliability is not always accounted for, but their presence alone creates a relativity of truth. And in the space left by the absence of grand narratives—not yet dead but ever imploding—those stories not yet fully formed have greater chance to flower, and fully grow.

Last year, I travelled by road with a group of young African writers, photographers and filmmakers known collectively as Invisible Borders from West to East Africa, through Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad, Sudan, Ethiopia, meeting with writers, choreographers, artists, and others along the way. What struck me the most, apart from the fact that none of the countries conformed to the ideas that had been constructed by stories in my imagination, was the plurality of narratives. In Sudan, for example, I spoke with two photographers, Issam Hafiez and Ala Kheir, both of whom had depicted Darfur, one had photographed the charred carcasses of horses in a village in the aftermath of an attack, the other a serene portrait of a tree by the side of the river near his hometown that was all stillness and peace. Both images represented how each photographer saw the area. Both were true.

The gaps in the way the countries of Africa portray themselves—not only to the outside world, but also to themselves—are not being addressed by governments except in cursory attempts at rebranding in tourism sectors. The weakness of governments in many African countries, governments still young, still inexperienced, still learning to walk and navigate, to inhabit their roles, has led to bodies like NGOs playing the parts that governments should. The problem with these well-meaning bodies is that more often than not, their employees are from elsewhere, separated by the windows of air-conditioned four-wheel drives, ex-pat restaurants and a lack of visceral knowledge of the languages and cultures, from the societies they have to come to help.

A recent phenomenon has seen the rise of independent spaces run by individuals and collectives who have been both nurtured and frustrated by the places they set up in, which offer spaces for research, for training, for the honing of critical facilities and exchange. In the arts, these spaces are working hard at breaking discourses out of the narrow confines of the art world and bringing them into the communities they are a part of. Spaces like Appartement 22 in Rabat, Morocco are creating exhibitions in public spaces like the market; Art Bakery in Douala, Cameroon is creating water purifying systems and radio stations; Townhouse Gallery in Cairo and Raw Material Company in Dakar, Senegal, are offering the populace the space to stop and reflect, and act as living archives, by exhibiting the symbols and images of the political shifts and upheavals happening in their countries. These initiatives are the result of a deeper engagement with their environments, with their historical and social needs and imperatives.

In these times of economic turmoil, the arts are the first thing to be cut back on, but in most countries of Africa, apart from those like Senegal, where art was written into the constitution by its first president, the arts and their possibilities were hardly supported in the first place. Travelling through the continent, it became very clear to me that these empty spaces were happily being filled by foreign cultural institutions, like the Institut Français and the Goethe Institut. Looking at their extensive program of concerts, talks and exhibitions, I felt uncomfortable with the role they were playing in shaping the cultural output of the continent, which seemed dangerously close to that of writing our narratives for us. At Condition Report, the symposium of independent art spaces organized by Raw Material Company in early 2012, representatives of these cultural institutions presented their programs couched in the language of help and support that echoed the frankly nauseating rhetoric of the NGOs. I put to them that we were all politically astute enough to know that no national body acts out of purely altruistic reasons and asked them for a level of transparency, or rather respect. It was Katharina von Ruckteschell from the Goethe Institut who offered it, by explaining then, and later elaborating in the essay she wrote for the forthcoming Condition Report publication, why the Goethe Institut has doubled its annual budget for the countries south of the Sahara, increasing it by more than five million euros, and is implementing program like Action Africa and Moving Africa, which bring African artists together for exchange at festivals, conferences and workshops. Germany had to position itself on a continent where the powers of the West were being “usurped” by the Chinese. It did not want to be excluded from the cultural discourse of things to come. “One thing is clear,” she writes, “the 21st century belongs to the South.”

This level of political honesty speaks of a shift of our ability to communicate as equals on even playing fields, even if one side, for now, more clearly realizes the vitality of cultural exploration and its outcomes and is more willing to materially invest in is. In Lagos, the independent Centre for Contemporary Art embodies this reciprocity, by insisting that its partnerships with institutions like the Tate be two-way, that exhibitions and residencies take place, not just in London, but also in Lagos. There is a shift towards transnational encounters, opportunities, and dialogues, which was nowhere more clear than at the Condition Report symposium. It was not just the natural understanding and openness that a symposium of independent art spaces from Africa could not just include those from Nigeria, Kenya, Egypt, and South Africa, but also from Korea, Mexico, Turkey, Norway and America. But also that they did not come together at the MoMA in New York or the Tate in London, but at an independent arts space I Dakar, creating new centers out of former peripheries. In this, it was taking a huge leap forward from events like the Rencontres de Bamako, the African biennial of photography, and Dak’art, the African contemporary art biennial, which are necessary and crucial in their own right, but limit themselves to arts from the continent and thus to a form of cultural isolation. Something is afoot in the world. Systems are breaking down, looking for new ways to express themselves, to redress deep, painful inequalities. New geographies, stories, connections are being sought. The murmurings of what these new realities might look like are not starting with those metropolises of the West that have set the tone from the beginnings of industrialization, but from Cairo and Dakar. Whilst places like Greece, in the face of the breakdown of existing structures, turn desperately to damaging mythologies of national purity and identity, recreating historical upsets, reliving their nightmares, in the Global South, new dreams are being dreamt and new languages are silently forming.

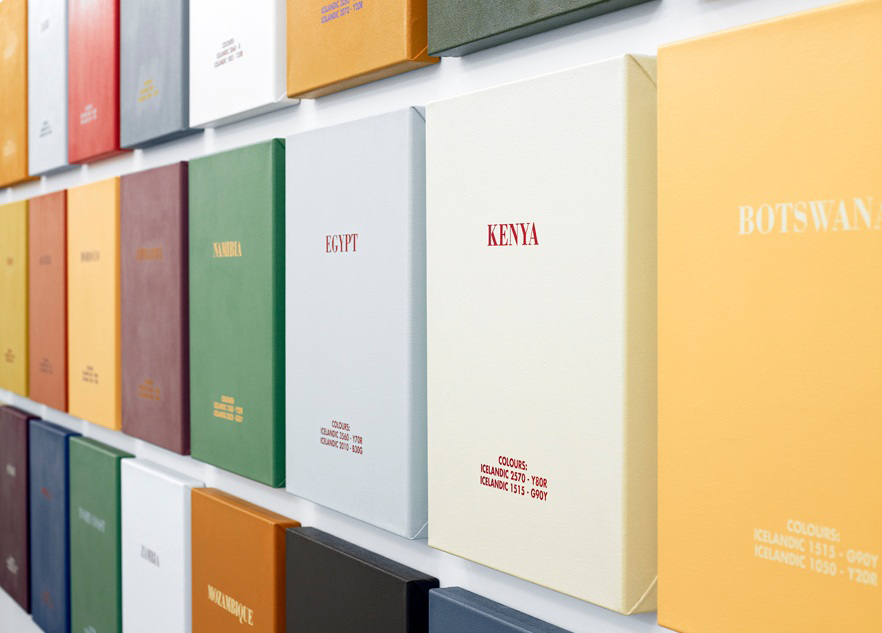

It is these monumental changes that the Cultural Encyclopedia, a massive documentation project that I’m currently involved in, will account for. For now the prism of the nation is still the most comprehensive one we have, even though it might not always be so. The Cultural Encyclopedia will map, in fifty-four volumes, the trajectories of historical and contemporary cultural production on the African continent. It will be headed by a core team based in Africa, but its expression will expand out to thinkers, artists, philosophers and scientists from across the world. It will be printed in book form on a model based on the Bibliothèque Bleue, which was distributed not just among an urban elite, but also amongst the masses, distributed through both the formal and informal networks, at petrol stations, through mobile vendors and markets, as well as on the Internet. It will not seek to be definitive, but create networks, build on, support and deepen the work of the independent centers on the continent, and be a resource for dialogue and questioning and rethinking, an ever-expanding, mirror accommodating the many different versions of the truth.