WEB SPECIALS

RE-BUNK!

words by Isobel Harbison

In 1946, a gang of artists, writers, poets and benefactors, with racy aspirations and an aversion to the trappings of a modern museum set up London’s ICA. The term “art center” seemed too parochial, and “society” too enclosed. “Institute” was fitting for a place of new art ideas coming together in diverse disciplines and self-defining curatorial forms. Its first exhibition,”40 Years of Modern Art,” was soon followed by “40,000 Years of Modern Art,” the playful revisionism reflecting its curator’s discursive, curatorial strategy of placing things among other things, shuffling between geographic domains and cultural histories.

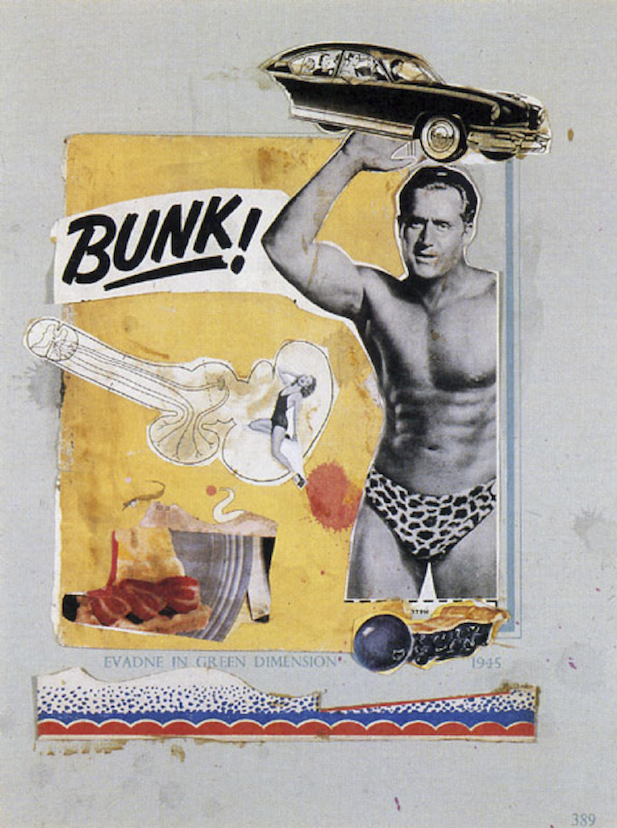

In 1952, BUNK! Happened A number of young artists, architects, writers and designers at ICA came to identify themselves as the “Independent Group” (IG). Critic and art historian Reyner Banham chaired its first meeting, in which art, philosophy and technology were discussed. BUNK! Consisted of a portfolio of new collages by Eduardo Paolozzi that were shown to the group, which included artists Richard Hamilton, John McHale and William Turnbull, photographer Nigel Henderson, designer Toni del Renzio and critic Lawrence Alloway. The subsequent sessions (between 1953 – 4), moderated by critic and curator Lawrence Alloway, brought architects Alison and Peter Smithson into the group and concentrated on mass culture, industrial design, cybernetics and fine ar. Sharing ideas and objects, they poured over glossy US magazines, motorcycle designs and discussed modern science and technology, nuclear war, robotics and the space age. All things bold, mechanic and new were welcome; all things knitted, etched or garden-grown, largely abandoned.

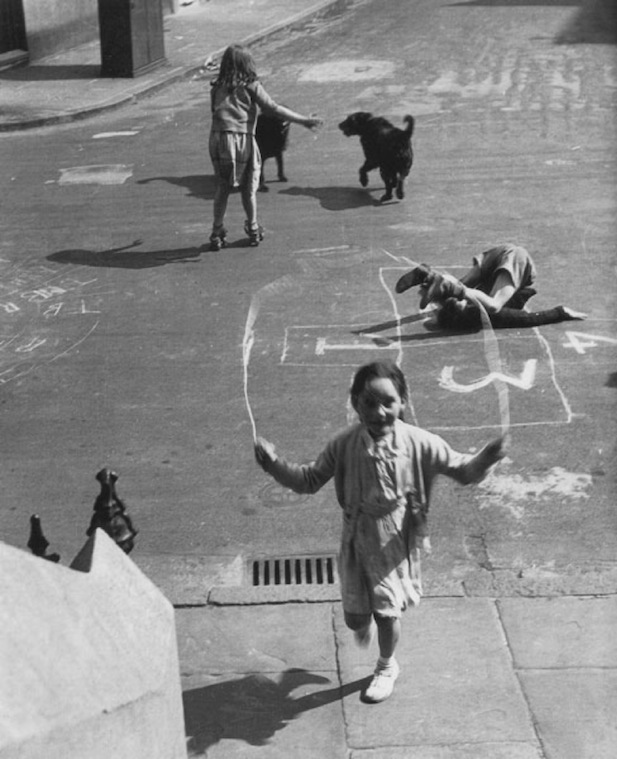

Courtesy of the Artist

BUNK returned in 2002. ICA recently held a conference, led by professor Anne Massey, on the life and legacy of IG, as it extends to art, architecture, music, design and education. Massey’s introduction included a sweep through literature published since her research for “The Independent Group: Modernism and Mass Culture, 1945-59.” (Manchester University Press, 1995) encompassing architecture; ‘Neo-avantgarde and Postmodern; Postwar architecture in Britain and Beyond’ (Yale, 2011), Richard Hornsey’s, ‘The Spiv and the Architect’ (University of Minnesota Press, 2010), to Maz Risselada and Dirk van den Heuvel’s look at Britain’s progressive Brutalists, ‘Alison and Peter Smithson: From the House of the Future to a House of Today’ (010 Publishers, 2004), to Charlie Gere’s broad study of ‘Digital Culture’ (Reaktion, 2002) and the recent Daniel Horowitz’s ‘Consuming Pleasures: Intellectuals and Popular Culture in the Postwar world.’ (Penn, 2012) Massey addressed the potential contradictions of historicizing a group that never set out to be a movement but rather an informal discursive faculty, informing and contributing to each other’s diverse works. She also pointed out the pitfalls of reductive teleological readings found in materials published over the last two decades, which deems the group the “fathers of pop.” From then on, a diverse group of academics shared their observations without permitting any post-hummus hardening of IG’s efforts into claims of an art historical “movement.” Art historian and critic John-Paul Stonard presented the “whirling phantasmagoria” of Paolozzi’s collages from the late 1940s and 1950s with particular attention to their source material from “lick the page” glossies imported from the US. He drew comparisons to the approaches of Manet, Stickert and Richter, all of whom reproduced pop images of their day, as well as Surrealist and Dadaist collages. In concluding, he revisite Alloway’s question: “how close can we get the source without abandoning art?”Richard Hornsey’s paper reflected on the “performance of citizenship” for queer men in post-war London and how this resonated with the IG’s emulation of the disorientating, overwhelming stimuli of a modern city and in their innovative exhibition designs, in particular “Parallel of Life and Art” (ICA, 1952), “This is Tomorrow” (Whitechapel, 1956) and “An Exhibit” (ICA, 1957). Barry Curtis’s dizzying presentation of the word “Tomorrow” and its different emotional registers—fear, excitement, greed—in the science fiction, architecture, art, design and assorted literature of the early 1950s was fascinating and often anecdotal, referencing his own experiences “growing up in the where’s-my-jetpack generation.” It is difficult to recount the breadth and depth of this talkand one would hope that this research will be published for the wider dissemination it really deserves.

Courtesy of the Artist

Another highlight from the day (I attended one, of two – so no doubt there were many more) was Alex Seago’s review of the changing aesthetics of the 1950s, as viewed through the front covers of the Royal College of Art’s then-student journal ARK,, which changed from folk to punk aesthetic almost overnight and included material from a range of editors and contributors that included Lawrence Alloway (“Technology and Sex in Sci Fi”) and Reyner Banham (“The New Looking Cruise Awaits”) to spreads by Richard Hamilton, Eduardo Paolozzi and even Ridley Scott. Benjamin Buchloh’s paper on Richard Hamilton’s relationship to the North American Pop artists, many of whom the latter encountered in work or person during his visit in 1963 to California to see a Marcel Duchamp retrospective. Formal comparisons of works by Hamilton, and Lichtenstein, Rauschenberg and Warhol were compelling. Hamilton’s responses seemed more cautious or sceptical than his counterparts’ “originals.”A final talk by Ben Cranfield explored IG’s critical methodologies, and transposed them against the initial boundary-pushing ambitions of the ICA itself. As an example, the exhibition “Growth and Form” (1951), which adopted the photogram as the conceptual curatorial framework (where, according to the Independent Group website set up by Massey, “Richard Hamilton created a complete environment—blown up microphotographs and X-rays were incorporated onto screens, films showing crystal growth and the maturation of a sea urchin were projected onto the walls in order that the spectator could be totally engulfed. Growth and Form was crucial for the Independent Group’s formulation of the expendable aesthetic….”). Cranfield’s talk highlighted the IG’s institutional provocations through curatorial forms, their casual pragmatism, their resistance to inherited institutional norms and forms and their insistence that—in Raymond William’s words—“culture is ordinary.”

The day provided many highlights and much food for thought. The conference brimmed with the International Group’s ground-level goodness, its sharp-focused reflections on global uncertainty and political promise, its desire for the tactile textures of new technology, its links to the Tomorrow-art of the past and of the present, its innovative curatorial ambitions and independence(OCCUPY, ahoy!). That to experience these offerings were relatively closed and costly is the unfortunate nature of the research-beast, however it would be a great shame if the re-BUNK! stopped here.