ISSUE 11Summer 2011

HIGHLIGHTS: Steven Shearer by Dieter Roelstraete; Slavs & Tatars by Carson Chan; Kaari Upson by Quinn Latimer; Alina Szapocznikow by Chris Sharp; Greg Parma-Smith interview by Nicolas Guagnini.

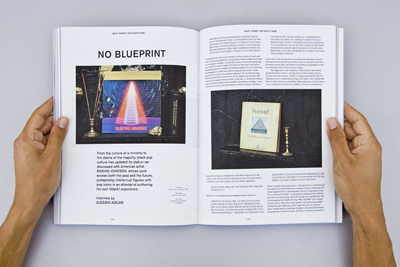

MAIN THEME: POP RIGHT NOW: Roundtable with Bettina Funcke, Massimiliano Gioni, John Miller, moderated by Joanna Fiduccia, with a postscript by Boris Groys, and artworks by Darren Bader; Justin Bieber by Francesco Spampinato; Rashid Johnson interview by Alessio Ascari; The Dark Side of Hipness Mark Greif and Richard Lloyd in conversation.

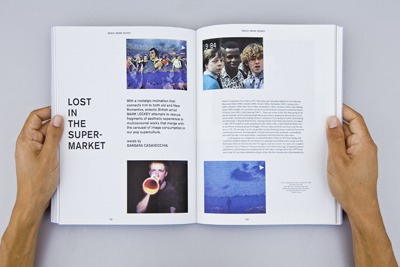

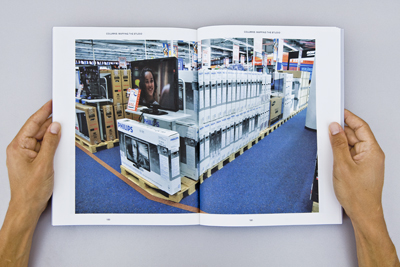

MONO: MARK LECKEY: Lost in the Supermarket by Barbara Casavecchia; The Browser Is a Portal by Isobel Harbison; Special Project by Mark Leckey; Art Stigmergy interview by Mark Fisher.

COLUMNS: PIONEERS: Morgan Fisher by Simone Menegoi; FUTURA: Helen Marten interview by Hans Ulrich Obrist; MAPPING THE STUDIO: Simon Denny by Luca Cerizza; CRITICAL SPACE: Douglas Coupland interview by Markus Miessen; ON EXHIBITION: Jeff Koons' "The New" by Paola Nicolin; LAST QUESTION: And What About Pop Music? answer by Scott King.

topPOST-WHAROLIAN MOURNERS

by DIETER ROELSTRAETE

STEVEN SHEARER, the representative of Canada at this year’s Venice Biennale, practices a dazzling pictorial experimentation engaged with a dense array of historical styles, from Impressionism to Expressionism, Fauvism, and Symbolism, while exploring the codes of suburban American pop culture.

Window, 2005

Courtesy: Stuart Shave/Modern Art, London,

Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich,

Galleria Franco Noero, Turin,

Gavin Brown, New York

Through no fault or design of my own, a chance visit to Minneapolis provided just the right inspirational occasion for jotting down a few thoughts on the new and not-so-new work of Vancouver-based artist Steven Shearer (b. 1968), whose drawings, paintings, and sculptures will occupy the Canadian Pavilion during this summer’s Venice Biennale. The occasion in question was an exhibition titled “The Mourners,” which I was fortunate enough to see at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. The exhibition’s titular grievers are a group of thirty-eight small alabaster sculptures, made in the fifteenth century by some of Europe’s finest stone carvers to adorn the graves of the Dukes of Burgundy: a procession of mournful, dejected looking monks, many with their hoods pulled over their contorted faces, languorously shuffling in and out of the labyrinthine structure (meant to evoke the entrails of a medieval Carthusian cloister) that forms the pedestal on which the life-size sculpted effigies of the ducal deceased lie enshrined.

Although I first got to know these extraordinary (and extraordinarily expressive) sculptures through a book that was given to me as a birthday present by another artist friend, upon seeing this morbid sepulchral extravaganza, my thoughts quickly wandered off to Steven Shearer’s studio—and they did so not just because “mournful,” “dejected,” “contorted,” “heretical,” “languorous,” “morbid,” and “sepulchral” are adjectives that are often (and, it should be added, often too easily) applied to Shearer’s own work.

topPOP RIGHT NOW

BETTINA FUNCKE, MASSIMILIANO GIONI and JOHN MILLER moderated by JOANNA FIDUCCIA with a postscript by BORIS GROYS and artworks by DARREN BADER

As we witness the unprecedented destruction of public space through digital media, the embrace of art and popular culture has grown increasingly complicated—demanding that its core contradictions be explored to unveil Pop’s enigmatic and ambivalent nature, and to discover how its legacy plays out in contemporary practices.

JOANNA FIDUCCIA: I want to begin today by speculating on the title of this roundtable, “Pop Right Now.” By virtue of addressing “right now,” the topic seems to suggest a notion of Pop untethered from its historical figures. To be “Pop,” then, becomes something akin to being “hip”—a value that lives and dies in its moment, and that is, moreover, non-genealogical. “Pop right now” looks to be less about a legible legacy of Pop art than about a set of tactics or maybe attitudes. I wonder how the title “Pop Right Now” struck you. For instance, Bettina, you have an investment in seeing how some of Pop’s core contradictions and aporia play out in contemporary practices, whereas John, many of your works engage commodity and taste in ways related to Pop operations, and Massimiliano, as a curator in a contemporary institution, you are perhaps living out certain ramifications of Pop on art’s relationship to the public sphere today.

#readmore#

JOHN MILLER: I think Pop is always obligated to represent itself in the present, but I would always look for historical underpinnings that are repressed or denied by a pop consciousness. Pop as a public sensibility is paradoxical today, because we’re witnessing the unprecedented destruction of public space through digital media. Even passing moments that used to be idle time or, oddly enough, public time, are being instrumentalized and capitalized. As a result, there’s a subliminal aspect to Pop now.

MASSIMILIANO GIONI: As a curator, I must say that I am not really sure if institutions and museums are pop; maybe they are popular or concerned with the public, but does that make them pop? The fact that institutions are trying to have a larger public doesn’t make them pop; it maybe makes them populist, though. To me, pop means embracing whatever is trivial and common, but in that embrace, something happens to both the commodity and the art, something that makes both more ambiguous. To me, the whole enigma of pop is how to embrace popular culture— how to be popular—and yet remain critical by maintaining a perverse relationship to popular culture. It’s an embrace of the obvious that makes the obvious much more complex, and that makes the subject of that embrace more complex as well.

BETTINA FUNCKE: Pop art is really a historical term, and somehow, the way we’re using Pop also sounds historical to me. Pop art engaged with pop or the popular in such a different situation than ours today. The complexities of artists looking at popular culture were so much more innocent and easy to grasp. Digitization and the advancement of technology complicated the relationship of pop and art. Contemporary art is more popular than ever, and at the same time, as you said, John, public spaces are shrinking. I wonder if Pop then is always contemporary, or is it something that had a historical moment that we’re now looking back upon?

MG: Perhaps it’s just a matter of categorization and definition. For example, for me, Pop is something that art does to popular culture. But the question that follows from that is: when art appropriates popular culture, does it appropriate it in a critical way? A very important element of the pop sensibility—in Jeff Koons, for instance, or in Warhol before him—is the ambiguity of the pop attitude. The most interesting Pop art has questioned the clarity of criticism: it has refused to take a clear-cut position in favor or against popular culture. You can say that Warhol is embracing popular culture, but you can also say that he’s criticizing it. The same can be said about Koons, but can it be said about Murakami? That, for me, is where the problem and the beauty of Pop reside.

BF: I was trying to think of “pop right now,” and some very different things came to mind—for example, how pop could also be threatening. Ai Wei Wei, because he has become pop, could even become an enemy of the state. And then, there’s a Warhol monument that Rob Pruitt just put up in Union Square. It’s a life-size Andy Warhol standing there with a Bloomingdale’s shopping bag, and it has a shiny silver surface that we know from Jeff Koons. At first I wasn’t into the sculpture at all, but then I kept going back to it—and there are always a bunch of people around it, talking about it, touching it, taking pictures. I figured, this is pop, and it’s really good at being pop. A third example is the John Knight show at Greene Naftali, called “Autotype.” Besides a huge print of the word “Autotype” in the otherwise empty gallery, the exhibition is porcelain plates hanging on the walls. They look Constructivist, but really, each plate is the outline of additions and extensions that museums are planning or have planned recently. The existing museum structure has been omitted, and so you only see this floating addition as an outline. It’s anti-pop, in fact—or it shows how un-pop the very popular museum is, because it’s missing its center.

JM: I like the distinction that the British critic George Melly drew between pop and popular in his book Revolt Into Style, where he discussed pop as a rupture with the popular, because pop wasn’t concerned with any kind of idealism. In his terms, it was motivated largely by material envy and by the desire to get ahead, to enjoy some kind of luxury. It’s interesting to see when it does come back around to a more idealistic political agenda; in the case of Ai Wei Wei, it seems to go back to the popular.

JF: I agree that there was an anti-utopian impulse to Pop proper, but also agree with Massimiliano’s characterization of Pop as fundamentally ambivalent with regard to impulses, and in particular, to its own critical potential. Given that institutional critique is now rapidly absorbed by the institution and by the frameworks that are its target, I wonder if Pop returns today because of the power of this ambiguity. That is, because this ambiguity provides resistance to this absorption…

MG: I think what we have today is a situation in which Pop is readily absorbed, and perhaps too readily absorbed, and maybe for all the wrong reasons. Is it okay to love a Jeff Koons piece and a Murakami piece just because they are popular? Or is it also about understanding what they are saying about commodity, our economy, and so on? Warhol and Lichtenstein had an element of friction in their works: when a movie lasts 8 hours, it’s not so easily assimilated; when a picture from a comic book becomes a painting, no matter how playful it might seem, it is still a major violation of the accepted values of high art. Now it seems, in the name of Pop, we just accept anything that makes us feel good. Koons is most interesting and problematic in his refusal of “criticality,” to quote from his famous ad inserts. He takes the end of criticality to an extent that becomes very problematic, at times almost clinical. His desire to be liked is somehow disturbing—and that can be a form of friction, too, I guess.

BF: What do you think happened between Koons and art today? Did Pop lose its ambiguity and therefore the interest of younger artists?

MG: Yes, I think you can see it in the trajectory of Koons himself, from the ambiguity and perversion of his position toward popular culture, to a place where the affirmation is so full and complete that I don’t know anymore if it is fair to talk about Pop or if we are just in the realm of pure entertainment. Pop, to my mind, is our contemporary equivalent to Classicism: Classicism played with antiquity; it assimilated antiquity and played with perfection. But the perfection of Classicism was always—how can I put it?—trembling. It was unstable; its interpretation of antiquity was alive and moving—think of Raphael or Michelangelo. It was never a formula. When Classicism becomes too perfect, then it becomes stale and turns into the more sterile Neo-classicism, into academicism. Something similar happens to Pop: you can embrace popular culture, but there should be some sense of a trembling instability, some sense of indecision, some sense of complexity. I have to look at the image and think, “Is this for real?” When I don’t ask that question, and when it’s just for real, then I think we are in a different realm, which is maybe the realm of entertainment.

BF: I’ve been trying to counter the feeling that all difference has been lost between high and low. In my book Pop and Populus, I wanted to redraw some of the distinctions, placing pop on the side of mass culture and the populace, as the people, on the side of high culture. Pop in this sense is popular culture; it’s very powerful because everyone wants it, but it will be forgotten in a few years, or at least in a generation. On the other side, high culture tries to protect certain parts of knowledge—historical knowledge—as a reference point from which to negotiate larger contemporary questions. Artists working today are caught in the tension between popular culture and the history of art, and this is the space in which the most interesting work is made. Massimiliano, it almost sounded like you said our antiquity today is popular culture. I have to pause and think about what that actually means.

MG: I think it’s interesting that your book was designed by Wade Guyton, whose work is very much focused on technology and particularly on everyday, available technology. Maybe we could go back to the question of technology as a defining element of Pop.

JM: To look at Pop in a genealogical way, it starts with industrialization. Some of the first industrial products emulated things that the aristocracy and the royalty had, but since they weren’t handcrafted, there was this element of “fakeness” to them. The desire for luxury becomes coupled to a guilty conscience that leads to one sort of modernist impulse: that ornamentation is corrupt and needs to be purged. If we think of Warhol as a dandy, we could equate him to Beau Brummell, who was engaged in a kind of class warfare, waged by practicing greater standards of hygiene and grooming than the even aristocracy. The sensibility was moreover subliminal; the idea was that the tailoring would be so good that it wouldn’t stand out. Jumping forward to now, I think that a similar duplication is going on that involves digital media; pop is occurring at a subliminal level that’s practiced generically, not simply as an artistic discourse, partly because the means of production are so readily available. There’s an ongoing flow of generic image production that carries a very uncanny charge.

JF: This way of producing looks very similar to a way of consuming today; both activities are processed through the same technological organs, where blogs and feeds become sites for both the consumption and the generation of more material. That makes me think about the distinction between high culture and mass culture, and where pop fits in. In the October issue on “High/Low”— almost exactly twenty years ago—Rosalind Krauss points to “pop culture” as a refusal of the Frankfurt School’s “mass culture” and its corresponding notion of the lumpen masses, in favor of a vision of individuals who can express some kind of active, critical potential in the act of consuming—that is, who can produce in consuming. But again, Krauss wrote that twenty years ago. Is there still a distinction to be made between mass culture and pop culture today?

MG: Personally, I don’t think so much of mass culture anymore. I am afraid that, in a way, the audience has taken the place of mass culture, and this audience is an audience of individuals. “Customization” has transformed mass culture from one big thing—which maybe was only a fiction in the first place—to something in which individual tastes are much more represented. The audience has also taken the place of the public—not just the public as the audience, but also the public as public space.

JF: So what is the distinction between audience and public?

MG: I think the audience tends to pay for the ticket. It seems like a simplistic definition, but the audience is intimately connected to a form of commerce. The word “public” comes with other associations that are perhaps more political, and more social, in nature. And coming from a country whose prime minister is Silvio Berlusconi, I think it’s clear that we have mutated into an audience even on a political level.

BF: For me, I would not use the terms mass culture or popular culture in relation to the museum, even though the museum has become way more popular than it used to be. But if you compare the numbers of museum-goers to people who go to the movies or sports events, the numbers are so hugely different that suddenly, art doesn’t really look like popular culture at all.

JM: I think it depends how you look at it, though. To go back to the analogy between sports stadiums and museums, yes, there are many more sports fans, but then again, almost any time a city builds an arena, it takes a loss, whereas museums have become powerful engines of economic renewal.

BF: I think about the museums being built in the Middle East, though, and I have a feeling it’s more about an image than the actual economy.

JM: Well, for example, the biennial has become the obligatory event of any government claiming to be a liberal democracy.

MG: Unfortunately, I think that the obligatory event is now the art fair; every city that wants to be international now wants an art fair. Going back to what you were saying, I think that the museum and the audience are crucial elements of this transformation— the popularization of art—but I don’t think there is a museum that is really Pop in the sense of having the freshness and excess of the Pop image. Even the Guggenheim Bilbao is still based on the idea of the museum as cathedral.

JM: I think Jérome Sans and Nicolas Bourriaud tried, with the Palais de Tokyo, to make a leaner version of a pop museum… And here in New York, the New Museum and Guggenheim would both really like to be pop.

MG: I think there is something confusing about pop, and so in a way it cannot become an institution. The exhibition “Pop Life” at the Tate is an interesting example, because the museum was trying so hard to be pop. It even had Keith Haring’s shop.

JF: The exhibition resorted there to a strategy of re-staging, which raises the question of what it would be to re-stage Pop, and thereby risk losing the immediacy you’ve pointed to…

JM: I have an anecdote about trying to buy something from Keith Haring’s Pop Shop. I needed something for a piece I was working on. First I looked online— you know, the Pop Shop had become this online operation—but they had some very complex credit card processing thing that ultimately didn’t work for me, so I just gave up on it. But then a week or two later, I was in a Duane Reade drug store and they had a rack full of Keith Haring baby bibs for $3 a piece. That’s what I ended up getting.

JF: So maybe there are still public spaces where we can find Pop.

JM: I paid the ticket price, so to speak. I was the audience!

BF: Early on, we said public space had been commercialized and taken over by other interests, although historically, it’s meant be free—a place where people can come together and be there without paying.

JF: I like Claude Lefort’s description of public space, “the image of an empty place,” and I think it might speak to the feeling of the absence of public space right now. There appears to be no more “empty place” left to us. Everything is saturated by information, images, products.

BF: Yes—historically, the public place was the space of the farmers market. Whenever the farmers market wasn’t happening, it became the public space.

JM: There’s also Negri and Hardt’s idea of the commons and the multitude. They’re trying to reclaim public space for the multitude, as opposed to masses.

JF: I think that goes back to Pop’s longstanding reaction to the stigmatization of the masses, and perhaps that means that Negri and Hardt’s concept of the multitude is not so far from pop culture, insofar as both are defending the idea of a creative individual—or consumer?—who, as Massimiliano pointed out, is constantly customizing her experiences and interactions.

MG: I think the commercial aspect is intimately connected to Pop. I mentioned the art fair earlier. We seem to assume that Pop is somehow about technology, but it’s also about commodities, and therefore about spending money, or wanting to spend money.

JM: Absolutely, and part of this is a questio of global demographics. Whereas I think of Richard Hamilton’s definition of Pop as “young, sexy, and gimmicky,” in many Western industrialized countries, the population is graying. What kind of pop culture do you have when young people are in the vast minority, when you have a country of senior citizens? That seems to be a very un-sexy scenario.

BF: So people are now researching how to make popular culture for the retired. It’s a huge market…

JM: Geriatric Pop!

POSTSCRIPT (BORIS GROYS): Pop art was a reaction to the mass culture of the postwar period—an attempt to create a framework for comparison between mass cultural images and the high art tradition of the past. I do not believe that such an attempt can be repeated because it seems to me that mass culture has disappeared, having been dissolved by the Internet. Contemporary culture is fragmented, and every fragment of this culture is equally globalized. There are worldwide communities of lovers of Zen Buddhism, hard rock, anthropophagy, and contemporary art. But these communities do not build any masses, and attitudes and images that capture or create masses do not exist anymore. At the same time, the cultural hierarchy among different global virtual communities of this type also does not exist—and such hierarchy is necessary for the functioning of Pop art. Every hierarchy is based on the difference in the possibilities for access. But today, everything is accessible (in symbolic, not monetary terms) to everybody.

On the other hand, Pop art can be seen as a kind of realism. Now, the return of and to realism is always possible—and, to a certain extent, has even happened today. Contemporary interest in the documentary as genre is proof of that.

—JOANNA FIDUCCIA is Associate Editor of Kaleidoscope. Her writing has appeared in Artforum, Spike, artonpaper, Art Lies, and MAP, as well as in catalogue texts for Lucy Skaer and Nina Beier. She currently lives and works in Los Angeles, where she is a Dickson Fellow in the Art History Department at UCLA.

—BETTINA FUNCKE is a New York-based writer and editor. She is currently the Head of Publications for dOCUMENTA (13). She has written and lectured widely on contemporary art and its production, and is the author of Pop or Populus: Art between High and Low(Sternberg Press, 2009). Her writing has appeared in artist monographs and journals, including essays on Wade Guyton, Gerard Byrne, Jacques Rancière, and Elad Lassry, as well as conversations with Kelley Walker, Carol Bove, Johanna Burton, and Peter Sloterdijk. She is also a co-founder of The Leopard Press and the Continuous Project group.

—MASSIMILIANO GIONI is the Associate Director at the New Museum in New York and the Artistic Director of the Nicola Trussardi Foundation in Milan.

—JOHN MILLER is an artist and writer based in New York and Berlin. Last spring, he received the Wolfgang Hahn Prize from the Gesellschaft für Moderne Kunst at the Museum Ludwig in Cologne. This fall, JRP-Ringier will publish a second English-language collection of his essays, The Ruin of Exchange: Selected Writings. Miller is a Professor of Professional Practice in the Art History Department at Barnard College.

—BORIS GROYS is a critic and curator based in Berlin. He is the curator of the Russian Pavillon at the Venice Biennale 2011. Among his recent books are History Becomes Form: Moscow Conceptualism(MIT Press, 2010), Going Public(Sternberg Press/e-&ux;, 2010, ed. with Peter Weibel), and Medium Religion(Koenig Verlag, 2011).

topART STIGMERGY

interview by MARK FISHER

In an increasingly dispersed world, MARK LECKEY rejects the self-referentiality of the art world in favor of being immersed in things through the benefits of technology— thus allowing an expanded field of sculpture to take shape between material and immaterial realms.

Drunken Bakers, video still, 2005

Courtesy: the artist and

Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York

© Mark Leckey

MAYBE WE COULD START OFF BY TALKING ABOUT THE ROLE OF POPULAR CULTURE IN YOUR WORK. WHY DO YOU FOCUS ON POPULAR CULTURE?

Popular culture is just things that are immediate to me. When I was in college in the ’80s, I found everything too detached or ironic, and I didn’t want to make work like that; I couldn’t make work with a critical disinterestedness. I decided that I should use as material my own history and background. “Fiorucci” was a way of digesting things that had happened to me personally, but also a history of where I had come from. I was a casual and a raver, so those are things I can speak of. My show at the Serpentine features a big fridge because that’s what is now in my local environment: domestic appliances. That’s what I have a relationship with now.

Read more