ARCHIVE

THE SUBTLE BODY

Danh Vo and Carol Bove in conversation with Elena Filipovic

Courtesy of Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York

Photography by Peter Muscato

ELENA FILIPOVIC Both of you readily admit the impact that Gonzalez-Torres has had on your work, and yet I have the sense that you are each provoked by different aspects of Gonzalez-Torres’s work. I wonder if you could say something about that?

DANH VO I have been very fortunate to have had many years of dialogue with Julie Ault, one of the founding members of Group Material, who was also the person who had invited Felix Gonzalez-Torres to join the group in the late ’80s. I can’t talk about the influence of Gonzalez-Torres on my work without mentioning her. Ault was also the person who gave me a profound insight into the works of Roni Horn and many other artists of Group Material, as well as into the political and cultural situation of the time. All this had also informed the work of Gonzalez-Torres. My way of thinking would not exist without this influence and insight.

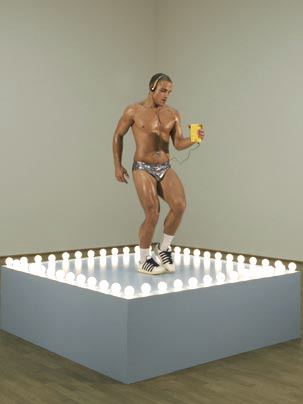

CAROL BOVE Yes, I think his work is a big influence for me. It’s not obvious, so I was pleased that you recognized a kinship. His works have a good balance of qualities I admire and strive for. They are delicate, romantic and intellectual, but also tough and angry. Casual, easy, precise, they’re also powerful and arresting. The animate quality of the objects is important. So is the self-evidence of the materials. The candies are candy to be used as candy. Both of these qualities—animation and self-evidence—talk about mortality and history, as well as the passage and experience of time.

Gonzalez-Torres was working in a time and place where artworks (as well as every other thing imaginable) were read as texts, and that perspective was a powerful shaping force, but his work takes on all of the non-verbal intelligence of human experience, too. His work takes political engagement and cultural theory as a starting point, but it also insists on an erotic dimension: that the work of art is not reducible to its interpretation and that its potential for real provocation is as much in the experience of the encounter as it is in the world of ideas.

I fantasize that there was a thrill for him in violating the taboo that kept formalism and conceptualism separate. His openness to beauty must have felt risky and totally conservative (i.e. risky for a political radical to work in a retrograde modality). Part of the pleasure in looking at art is in developing the faculties to perceive mutually exclusive positions without contradiction. But anyway, these approaches are not opposed; even if an artwork could be inserted directly into the viewer’s mind, I would consider that to be sculpture and it would still have a form.

EF This is not the first time each of you have made decisions of a “curatorial” order about how your artwork or even the artwork of others should be presented, displayed and installed, but it is the first time either of you have been asked to curate a solo exhibition (a retrospective, even) of another artist’s work. Are there particular considerations that made thinking about and curating your versions of a Felix Gonzalez-Torres exhibition more difficult than simply thinking about how to show your own artwork?

DV I don’t think there is any comparison. I mean, making a retrospective of my own work would be impossible. But what I can emphasize is the pressure I felt of having the responsibility in a retrospective of an artist’s work to present a “large” body of work (I’m still not sure if it was because of the idea of the retrospective itself or because of the large space that I was expected to fill with his artworks). I never thought of my version of this retrospective as necessarily needing to present a lot of pieces. This is probably because I always saw Gonzalez-Torres’s work as being easy to enter but difficult to grasp, always escaping you. For me, it is one of the most impressive characteristics of his production. I really tried to aim for this quality in my way of structuring the exhibition. That was more important than presenting quantity.

CB Yes! I’m so glad I’m not a curator regularly— I really don’t envy you. It’s so hard! On this occasion, I am thinking about what it means to be responsible in the context of presenting a retrospective, which is a new challenge. Respect is important. I’ve thought a lot about how to show respect for the man and for the artwork. But I’ve asked myself, would he want a servant? I doubt it! And even if he did want a servant, should I supply one? Admiration and regret over his short life make me feel compelled to search for clues as to what he might have wanted me to do. Part of me wants to honor him by pleasing him. But I’m not convinced that fulfills my responsibility and I’m trying not to be distracted by those ideas.

I decided it’s important instead to historicize his work. No one wants the violence of historicism foisted upon his work, but this is part of the purpose of a retrospective: to separate a body of work from the fluid passage of time. When it’s separate, we can see its features. I want to arrest the work so we can encounter it anew and so we can interpret it. I want to look back on it in the context of its time, but also to see how its meaning has developed in the space between its invention and the current moment. I want to show it both continuous and discontinuous with history and the passage of time.

Photography by Sven Laurent

Collection of Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

EF speaking of time and history in relation to the making of a retrospective, the reason I had wanted to have not one but several versions of the exhibition— each one different from the others and involving choices that might even seem to be in contradiction with each other—was partly to break down the authority of that thing called a “retrospective.” This was necessary, i thought, because Gonzalez-Torres himself thought so much about and worked so much toward questioning authorities of every kind. A classical retrospective invariably posits a list of works as the most important or representative of an artist’s career, and the exhibition’s ordering of those artworks (chronological, thematic, whatever) as the way to read and understand the oeuvre—and the whole is typically presented as a neutral, objective inevitability. And it then enters history that way. So much of what Gonzalez-Torres did in his life and work aimed to counter this, so an exhibition dedicated to him today should find, I thought, a means of honoring that. I asked each of you to participate in interpreting his work (as well as Tino Sehgal, who still has some time to think about and plan his version, set to open in early 2011), and in giving form to that (necessarily subjective) interpretation in your version of the exhibition. When I invited you to work on this with me, you both seemed to understand immediately why this might make sense in relation to Gonzalez-Torres’s work…

DV I don’t recall that… I only remember that I was both tempted and afraid. I don’t feel like I have seen a good installation of Gonzalez-Torres’s work, since I only saw the work after his death. I must admit that I thought it was such a scary challenge that when I accepted it, I only could focus on my part of the overall concept and my own approach to it. I don’t know how you managed it, Superwoman!

CB Speaking to your point about arranging the “greatest hits” in chronological order: There are individual pieces, but there are also pieces in relation to other pieces and in relation to the world. They indicate the things around them. They point at the world and the world points back. And they perform differently under various circumstances. It makes no sense to disaggregate them. Or, it makes sense, but important qualities are lost.

Gonzalez-Torres’s work needs to be animated by the people who exhibit it. I think about his instructions as the written play and the curator as the director. If the curators don’t allow themselves some freedom to get it wrong or to show their own tastes and mannerisms, the viewer senses the inhibition and insecurity and the artworks become reenactments of the originals, which is a serious loss of status. Gonzalez-Torres invites the exhibitor to co-author the piece. But this places a curator in an awkward position because in order to freely interpret the work, he or she would end up taking some credit as the author: curators might feel it’s inappropriate or worse, hubristic, to act as author. They are allowed to construct the framing, the conceit, the platform, but they don’t co-author artworks.

Our expectations for curators are that they aspire to some kind of neutral objective position. Of course, we all also know that what we demand is impossible. It doesn’t make sense to me that curators are given an impossible job, but that’s the way we have it organized right now. Artists, on the other hand, are supposed to be authors all of the time. All of an artist’s gestures are read for content, so we read the presentation as an allegory of his or her own artwork. Sharks bite, bees sting, artists author.

Photography by Sven Laurent

EF Indeed this points to one of other reasons that the particular concept or methodology (if one can call it that) of this exhibition made sense for this specific body of work: I thought it is important to find a way to make an exhibition that would show, in the very structure of the exhibition, the fundamental malleability and vulnerability at the heart of Gonzalez-Torres’s work, but also, and relatedly, the question that he posed of authorship (with all its implicit and etymological links to “authority”). Was it easy for you to deal with the liberty his work offers and the responsibility that liberty necessarily implies?

DV There is no liberty. It’s like almost anything else: there’s a carrot for the donkey. We have to deal with issues like stiff institutions, economy, ownership and our own choices, which are not free. It’s a trap.

CB I don’t know if it’s easy or difficult, but in order to present something exquisite and delicate in an exhibition context, there needs to be some mechanism in place to protect it. I’m working on some protections. I’ve seen the vulnerability of Gonzalez-Torres get lost in presentations of his work, so I know it’s a challenge to create the right kind of platform. The first strategy I’m using is to start with a known script—a recreation of one of the shows Gonzalez-Torres made in 1991. This limits my ability to be inventive, which would be distracting. It would place emphasis on my choices as opposed to the finer points and the invisible dimension of the works.

Then I plan to physically protect the objects in the exhibition. I plan to spend the month of the exhibition in Basel and make regular visits to maintain it. The artworks need care. They need animation by the exhibitor, but they also flourish in conditions where they are given attention. The invisible dimension is powerful and vulnerable. Service renews them.

I sense in Gonzalez-Torres’s work so much indignation, anger and rage. These qualities get underemphasized in many hangings of the work. I hope I can mobilize the violence in his work as another protective element.

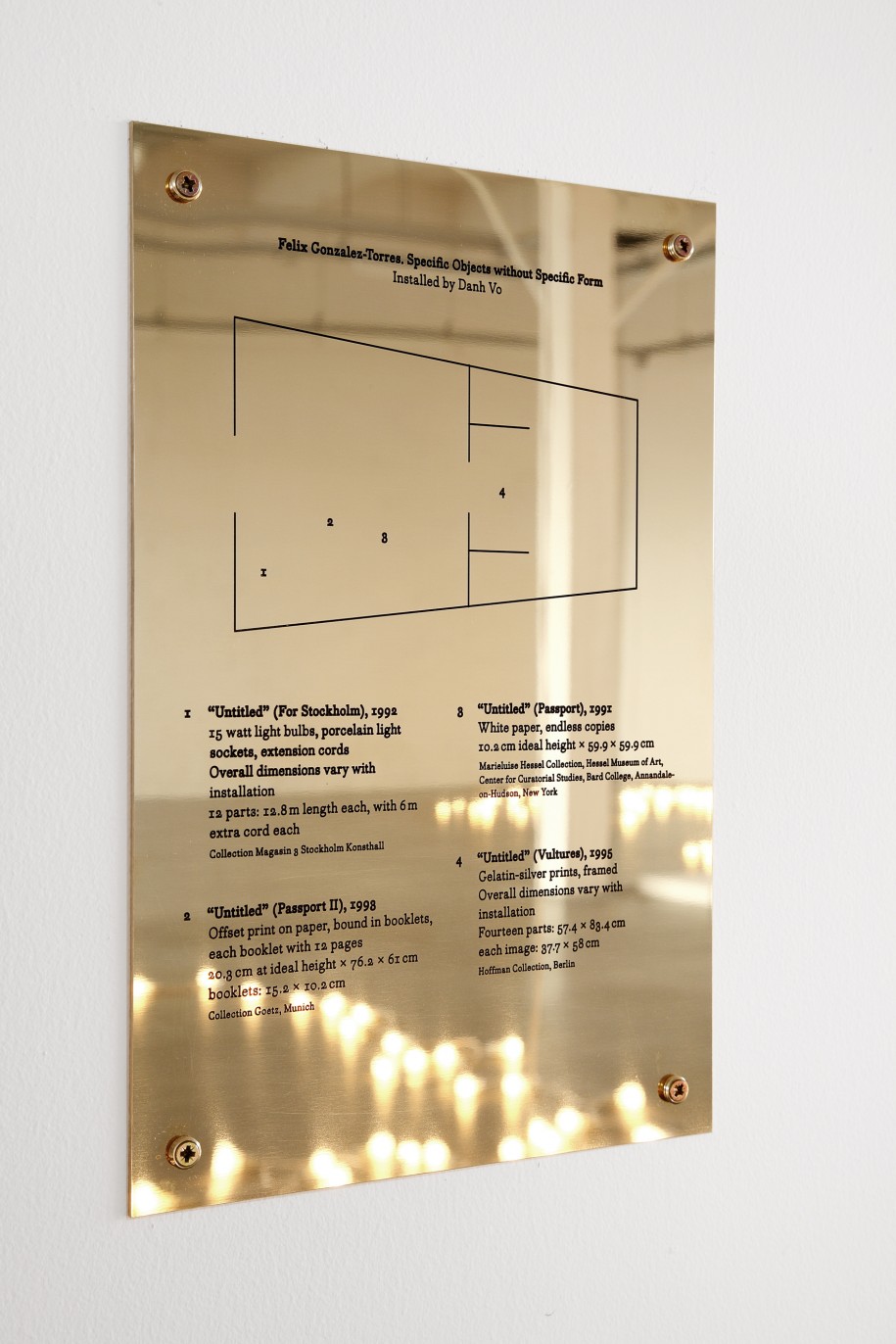

EF Exhibitions are, by definition, ephemeral. For a certain defined period of time, a certain constellation of objects occupy a space but will very likely never again be together in the same space or shown in the same way. The juxtapositions of one exhibition are rarely repeated. This is a fact. You are both concerned precisely with the implications of this ephemerality in your own work. I know it has motivated you, Danh, in each of your own exhibitions to have brass plates engraved with the floor plans and the list of works. I always understood these plates as a way to memorialize, or freeze in another form, that fleeting constellation of things that make up an exhibition. You asked me to have plaques made for your version of the Gonzalez-Torres show, which made perfect sense to me as a curatorial gesture. My labels were in white cardboard, yours were in brass, but both were ways of conveying essential exhibition information…

DV I like that we memorize certain things, but they can be fleeting, even if engraved in brass. The plaque is a door sign; it doesn’t mean the show will be staying there forever. I think the more important aspect of the brass plaques is their way of emphasizing information that is as important as the artworks themselves and reversing the distribution of information. Keep in mind that my brass plaques are always displayed in locations in the exhibition space that visitors reach after they have encountered the artworks being referred to. For me, the plaque was very necessary for the work of Gonzalez-Torres, because I wanted to have people see images of the sky or a bird, or a blank sheet of paper or light, without any inflection of meaning. Later, one can insert the possibility of meaning. I believe in that way we keep things more open.

I can’t help but think of something Douglas Crimp once said about Richard Serra’s work in which he pointed out that it would be wrong to think of Serra’s sculptures as obsessed with power and masculine just because of their size and materiality, as if modesty or ephemerality were feminine. Power relations are much more complex. Yes, engraved brass is perhaps like something carved in stone… but a brass plate can also be melted down. I think my informational plaques aspire to be like the use of parentheses in the works of Gonzalez-Torres: they are not an artwork but tell something about the artwork; there is something both present but also intimated or suggestive about them.

Photography by Sven Laurent

Collection of Dallas Museum of Art

EF And for you, Carol, it seems that this issue of memorializing ephemerality is expressed partly in your decision to recreate (or re-enact) one of Gonzalez-Torres’s landmark but little-known shows, which happened to be one of his most emphatically ephemeral, since he changed the contents and order of the exhibition display every week during the four weeks of the show.

CB I would be happy if I could find a way to talk about the energetic qualities of an exhibition. That would be enough. The strategy of placing things and artworks in relation to each other and in relation to all of the structures and forces—visible and invisible, material and imagined, ideological, historical, etc., that comprise the exhibition context—this set of relationships between things resists objectification. It’s the “subtle body” of an exhibition.

In part to show that, I’m planning to represent Gonzalez-Torres’s 1991 exhibition, “Every Week There Is Something Different,” which changed every week of its four-week run and will in Basel as well. I will try to faithfully reproduce the original exhibition, changing it every week and recreating the four original configurations of artworks. Because the larger project, this retrospective as a whole, will take so many forms, there’s no pressure to show a complete picture of his work, to represent a little bit of everything. That’s very nice, because otherwise this particular idea would be impossible to include, even though it shows an important part of Gonzalez-Torres’s work that would otherwise be hard to see: artworks in their original configurations. I don’t think it’s fetishistic at all to want to recreate these relationships. Gonzalez-Torres was working across different media with different display strategies in part because of the demand it places on the viewer to become conscious of how he or she approaches each work in a single exhibition. I’d like to see for myself what types of dialogues he set up.

Of course, it will be totally different from the original exhibition. Time-travel is impossible and besides, it’s in a different place on earth. It will be a re-staging, with all of the interesting problems that that endeavor necessarily invites.

With it, I want to show how situation-responsive artworks perform with varying degrees of exertion. I try to do this by displaying both the recreation of “Every Week Is Something Different” and the storage area for the artworks that go into it. In the storage area, artworks will be present for the public but not yet “on exhibition”; they might lean against the wall or still be wrapped or in a storage crate. So, in one space, the artworks are performing while, in another, they are in a state of rest. It’s a form of magic that a box of candy in one room can be transformed into a sculpture just by being unwrapped and laid on the floor in the next room.

EF I knew when I invited you that the shows you would make would be shows about and of Gonzalez-Torres, but that each show would invariably also reveal something about your aesthetics and practices. For me, that potential wasn’t something that menaced this project or rendered it ambiguous (it is still a retrospective of Gonzalez-Torres and not anything else), but that is probably because i don’t believe exhibition-making is an objective enterprise or that it should be done as if it were. I think this retrospective makes that explicit. Still, it has been said by some people who saw Danh Vo’s version of the exhibition that it looked very much like one of Danh’s shows of his own work. I wonder, Danh, if you feel that to be the case?

DV If people saw my Gonzalez-Torres exhibition and thought that it looked like exhibitions of my own art, that’s a problem of short-term memory, because if you look closer at the documentation of Gonzales-Torres’s installations, you’ll discover how much I ripped him off…

EF And Carol, although your version has not opened yet, i wonder how you see those choices you are planning in relation to your own practice?

CB The connection between the exhibition of Gonzalez-Torres’s work I have planned and my own shows might not be immediately legible but, of course, there is one. With my own work, I try to use a light touch, to do as little as possible and invent as little as possible. I don’t want to alter materials; I’d prefer to re-present them. I think about working into the field around objects rather than on the objects themselves. I’ll approach exhibiting Gonzalez-Torres’s work the same way: I want to make choices that don’t call attention to themselves.