ARCHIVE

THE RESURGENCE OF R&B

words by Tim Small

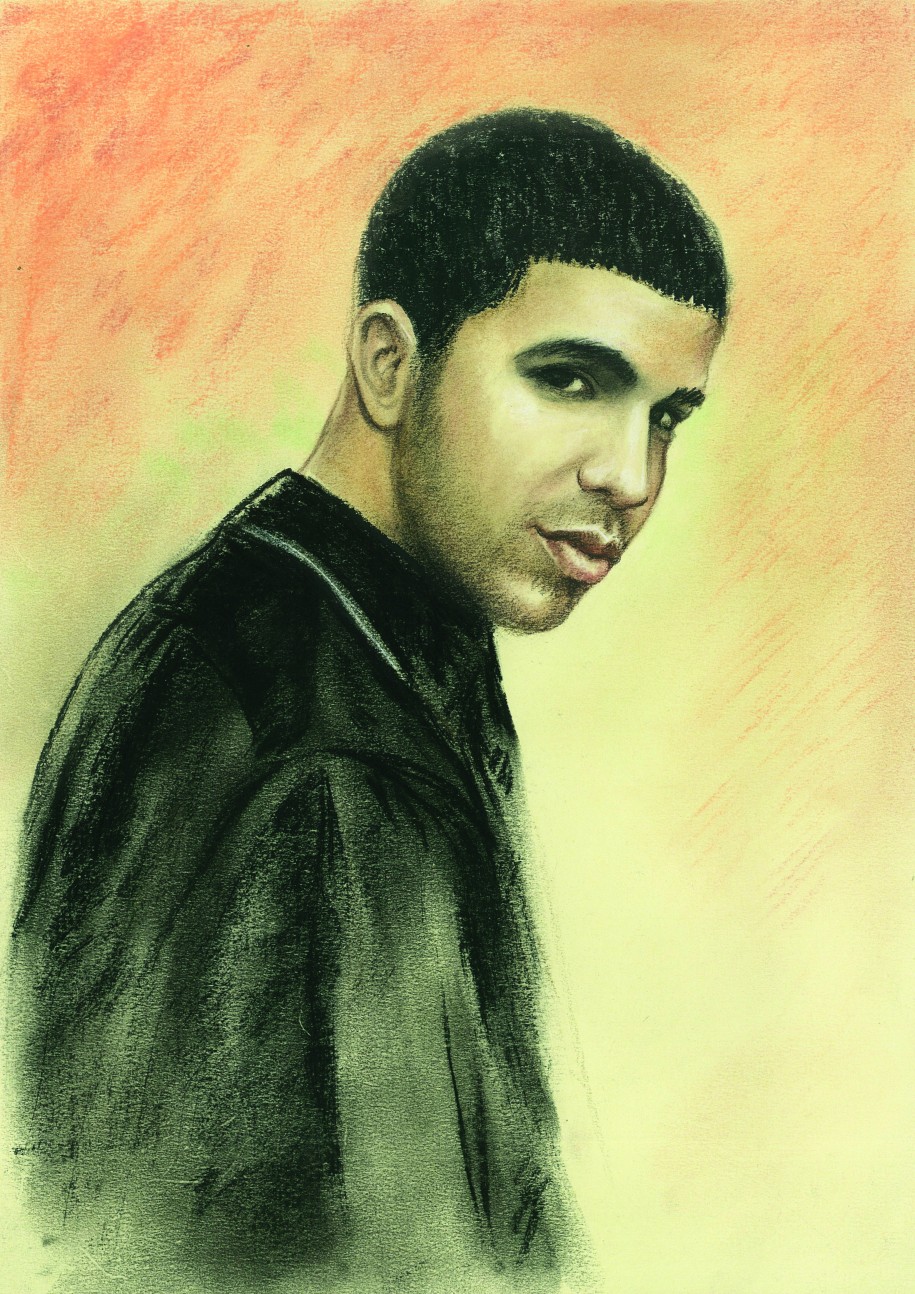

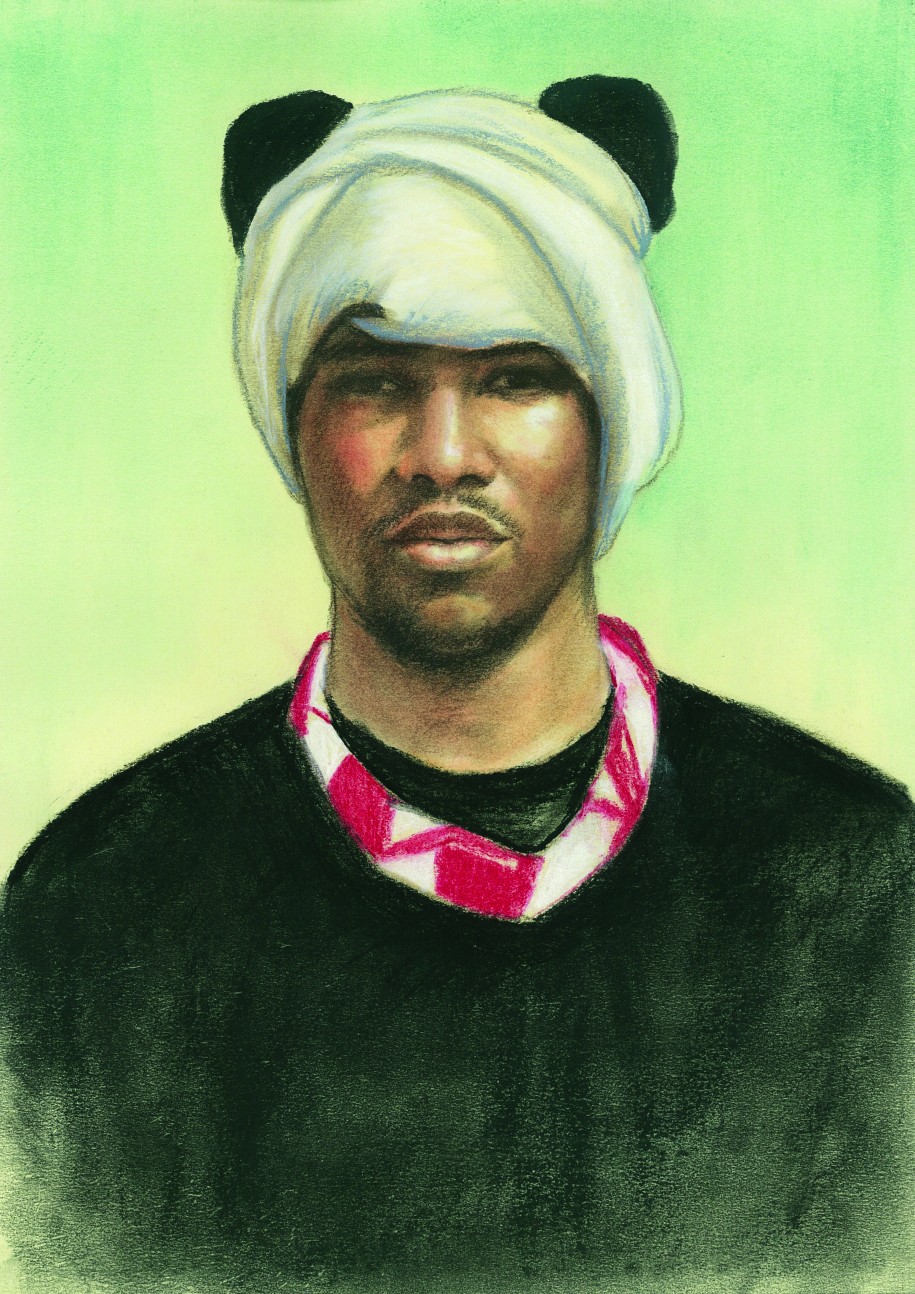

When, a few years from now, we look back at what’s happening now in pop music, we won’t be able to escape discussions of the resurgence of R&B. The contemporary renaissance of smooth sounds and soulful crooners has been felt at every end of the music world. The past eighteen months gave us a major breakthrough R&B / rap / pop record (Drake’s Take Care) and a solid third outing from the new king of commercial R&B (The-Dream’s Love King); a handful of fantastic releases from ethereal, mysterious acts that re-interpret the genre in less conventional, more experimental ways (Autre Ne Veut’s eponymous album and Body EP, How To Dress Well’s Love Remains and Just Once EP, and D’Eon and Grimes’s Darkbloom); hybrids like Frank Ocean’s nostalgia, Ultra, and The Internet; and, of course, the now-legendary three mixtapes by The Weeknd (House of Balloons, Thursday and Echoes of Silence).

What’s truly curious is that all these releases popped up at around the same time, and that it was, apparently, the perfect time for them to do so. In a way, we’ve been spectators at one of those rare convergences in the history of pop music, where both the public’s and the critic’s desires are met and our collective imagination tickled. It’s like we didn’t know we missed ’90s R&B as much as we did. Somehow the Gods of Music knew, and regaled us with a massive amount of quality smooth music in a wide variety of inflections, themes and styles, with something more or less for everybody’s taste — from The Weeknd’s cold, nocturnal, dark-hangover-after-the-A-list-party sound to Frank Ocean’s solid-while-weirdly-out-there soul; from The-Dream’s sleek productions and catchy hooks to Autre Ne Veut’s playful, leftfield, artsy take on Prince.

What do all these have in common? Quite simply: softness. As Pitchfork’s Nitsuh Abebe said in the November 7 entry for his fantastic column Why We Fight, “most music lovers carry around some shred of a very powerful myth, that pleasant music can never really be where the meaningful ideas are… It is, allegedly, the sound of complacency, boredom, and undeserved comfort. Niceness is for wimps and sell-outs, a bland little house in a repressed little suburb; everyone knows the real power of music is built from aggression and loud noises in dirty basements, transgression and energy and screams.” Abebe nicely sums up the argument with a droll, but acute statement: “What we’re talking about is a Baby Boomer myth of rock’n’roll.” To paraphrase the title of his article, beauty — and smoothness, and melody — does not have to be dull. Try giving a listen to Destroyer’s Kaputt, one of my personal favorites of 2011, to confirm it. And keep in mind that those Baby Boomers then went on to adore Abba.

Why exactly this is happening right now, I don’t know. Arguably, the past decade of pop music hasn’t been much more than an interminable tumble of retro stylings, a succession of re-imaginations. We had the stoner, grunge and shoegaze revival and the tail-end of ’90s jungle and two-step snapping back in the form of dubstep and wobble. It’s not a stretch to say that Simon Reynold’s Retromania perceptively summarized what this last musical decade was all about: a celebration of yesteryear. Everything that happened in decades past was re-packaged, re-filtered through modern sensibilities and re-presented to us. Maybe R&B was simply the last thing left. That one genre that still had to be re-processed and re-filtered for our renewed enjoyment.

Personally, I reject this theory. The idea that the music we’re currently re-filtering and re-processing now wasn’t in the first place re-processed from something even older is ridiculous. We’re all just constantly listening and learning, going through our father’s and our older brother’s records, remembering what we liked when we were thirteen with a skewed, personal eye, putting all of it down as an “influence” on the music we make today. This is not new. People have been doing that since popular music began. Furthermore, it’s not that hard to see a trajectory in recent R&B music that starts with Terry Riley, goes on to Timbaland’s productions for Aaliyah, then on to Pharrell, through Drake’s first mixtapes, and ends with The Weeknd’s sampling of Aaliyah in his own work. Yes, what’s different is that perhaps The Weeknd’s other references are more out there than Timbaland’s — Siouxsie and the Banshees aren’t exactly classic R&B — but then again, Timbaland’s references were way out there when compared to whoever came before him. And yes, as Tom Ewing rightly points out in his article for The Guardian,” The Weeknd’s suggestion that there’s an awfulness at the heart of VIP-area hedonism is always going to delight the indie crowd.” But what about Kanye’s same suggestion? Or T.I.’s? Might it not be, simply… true? Furthermore, The Weeknd’s Echoes of Silence opens with a cover of Michael Jackson’s “Dirty Diana” — not Einstürzende Neubauten.

In hindsight, everybody’s wise. It’s easy to interpret what happened thirty years ago, but things get harder when we talk about eight, five, three years ago — and talking about why things are relevant while they’re still happening is trickier still. One of the reasons for this is that we lack the vocabulary to communicate precisely what we’re observing. When a cultural phenomenon blossoms in real time, people tend to have trouble simply talking about it, because the words that accurately define what they’re witnessing don’t really exist yet. Somebody, somewhere has to invent them. Unfortunately, this is the job of “music journalists.” In the past few years, we’ve had to read frankly embarrassing terms for only relatively embarrassing music: we’ve had “shitgaze,” “rape gaze,” “witch house,” “witch,” “drag,” “chillwave,” “juke,” “footwork,” “slutwave,” “glo-fi,” “nu gaze,” “fidget house,” and so on. Sadly, some writers have referred to this music as “Hipster R&B.” Others simply called it R&B for white people. And it’s wrong, so wrong, for so many reasons. First off, we should never make the mistake of ascribing the values and characteristics of the people who consume or appreciate a certain art form to the intentions of the artist. Secondly, this term implies that white people don’t like “regular” R&B, like, say, R.Kelly (which is just openly racist). Thirdly, it negates the very origin of the word “hipster.” This is not “black music for white people,” as the term seems to suggest. It’s just music. Yes, white people do like The Weeknd, but how is that news? Haven’t white people been listening to Jay-Z, Tupac, Prince, Michael Jackson, James Brown, Stevie Wonder, Otis Redding, Funkadelic, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Artie Shaw? Think about the countless black artists in the history of jazz, blues, soul, R&B, hip-hop, funk, reggae, even punk. And think of the billions of white people, everywhere, since the dawn of time, that have enjoyed their music.

Either they’re all hipsters, or none of us are.